Posts Tagged mTBI

[WEB] Is TBI a Chronic Condition?

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in TBI on January 21, 2024

People with traumatic brain injury (TBI) may continue to improve or decline years after their injury, making it a more chronic illness, according to a study published in Neurology, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology.

“Our results dispute the notion that TBI is a one-time event with a stagnant outcome after a short period of recovery,” says study author Benjamin L. Brett, PhD, of the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee. “Rather, people with TBI continue to show improvement and decline across a range of areas including their ability to function and their thinking skills.”

The study involved people at 18 level 1 trauma center hospitals with an average age of 41. A total of 917 people had mild TBI and 193 people had moderate to severe TBI. They were matched to 154 people with orthopedic injuries but no head injuries. Participants were followed for up to seven years.

Participants took three tests on thinking, memory, mental health, and ability to function with daily activities annually from two to seven years post-injury. They also completed an interview on their abilities and symptoms, including headache, fatigue, and sleep disturbances.

When researchers looked at all test scores combined, 21% of people with mild TBI experienced decline, compared to 26% of people with moderate to severe TBI and 15% of people with orthopedic injuries with no head injury.

Among the three tests, researchers saw the most decline over the years in the ability to function with daily activities. On average, over the course of 2 to 7 years post-injury, a total of 29% of those with mild TBI declined in their abilities and 23% of those with moderate to severe TBI.

Yet some people showed improvement in the same area, with 22% of those with mild TBI improving over time and 36% of those with moderate to severe TBI.

“These findings point out the need to recognize TBI as a chronic condition in order to establish adequate care that supports the evolving needs of people with this condition,” Brett says. “This type of care should place a greater emphasis on helping people who have shown improvement continue to improve and implementing greater levels of support for those who have shown decline.”

A limitation of the study was that all participants were seen at a level 1 trauma center hospital within 24 hours of their injury, so the findings may not apply to other populations.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institute on Aging, the National Football League Scientific Advisory Board and the U.S. Department of Defense.

[WEB] New Data on Traumatic Brain Injury Show It’s Chronic, Evolving

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in TBI on January 20, 2024

New longitudinal data from the TRACK TBI investigators show that recovery from traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a dynamic process that continues to evolve well beyond the initial 12 months after injury.

The data show that patients with TBI may continue to improve or decline during a period of up to 7 years after injury, making it more of a chronic condition, the investigators report.

“Our results dispute the notion that TBI is a discrete, isolated medical event with a finite, static functional outcome following a relatively short period of upward recovery (typically up to 1 year),” Benjamin Brett, PhD, assistant professor, Departments of Neurosurgery and Neurology, Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, told Medscape Medical News.

“Rather, individuals continue to exhibit improvement and decline across a range of domains, including psychiatric, cognitive, and functional outcomes, even 2 to 7 years after their injury,” Brett said.

“Ultimately, our findings support conceptualizing TBI as a chronic condition for many patients, which requires routine follow-up, medical monitoring, responsive care, and support, adapting to their evolving needs many years following injury,” he said.

Results of the TRACK TBI LONG (Transforming Research and Clinical Knowledge in TBI Longitudinal study) were published online June 21 in Neurology.

Chronic and Evolving

The results are based on 1264 adults (mean age at injury, 41 years) from the initial TRACK TBI study, including 917 with mild TBI (mTBI) and 193 with moderate/severe TBI (msTBI), who were matched to 154 control patients who had experienced orthopedic trauma without evidence of head injury.

The participants were followed annually for up to 7 years after injury using the Glasgow Outcome Scale–Extended (GOSE), Brief Symptom Inventory–18 (BSI), and the Brief Test of Adult Cognition by Telephone (BTACT), as well as a self-reported perception of function. The researchers calculated rates of change (classified as stable, improved, or declined) for individual outcomes at each long-term follow-up.

In general, “stable” was the most frequent change outcome for the individual measures from post-injury baseline assessment to 7 years post injury.

However, a substantial proportion of patients with TBI (regardless of severity) experienced changes in psychiatric status, cognition, and functional outcomes over the years.

When the GOSE, BSI, and BTACT were considered collectively, rates of decline were 21% for mTBI, 26% for msTBI, and 15% for OTC.

The highest rates of decline were in functional outcomes (GOSE scores). On average, over the course of 2 to 7 years post injury, 29% of patients with mTBI and 23% of those with msTBI experienced a decline in the ability to function with daily activities.

A pattern of improvement on the GOSE was noted in 36% of patients with msTBI and 22% patients with mTBI.

Notably, said Brett, patients who experienced greater difficulties near the time of injury showed improvement for a period of 2 to 7 years post injury. Patient factors, such as older age at the time of the injury, were associated with greater risk of long-term decline.

“Our findings highlight the need to embrace conceptualization of TBI as a chronic condition in order to establish systems of care that provide continued follow-up with treatment and supports that adapt to evolving patient needs, regardless of the directions of change,” Brett told Medscape Medical News.

Important and Novel Work

In a linked editorial, Robynne Braun, MD, PhD, with the Department of Neurology, University of Maryland, Baltimore, notes that there have been “few prospective studies examining post-injury outcomes on this longer timescale, especially in mild TBI, making this an important and novel body of work.”

The study “effectively demonstrates that changes in function across multiple domains continue to occur well-beyond the conventionally tracked 6–12-month period of injury recovery,” Braun writes.

The observation that over the 7-year follow-up, a substantial proportion of patients with mTBI and msTBI exhibited a pattern of decline on the GOSE suggests that they “may have needed more ongoing medical monitoring, rehabilitation or supportive services to prevent worsening,” Braun adds.

At the same time, the improvement pattern on the GOSE suggests “opportunities for recovery that further rehabilitative or medical services might have enhanced.”

The study was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Institute on Aging, the National Football League Scientific Advisory Board, and the US Department of Defense. Brett and Braun have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Neurology. Published online June 21, 2023. Abstract, Editorial

[Abstract] Physical exercise for people with mild traumatic brain injury: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in TBI on March 8, 2023

Abstract

Background: Recent research recommends physical exercise rather than rest following a mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI).

Objective: To determine the effect of physical exercise on persistent symptoms in people with mTBI.

Methods: A search of randomized controlled trials was conducted in CINAHL, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, MEDLINE, SportDiscus and Web of Science, from 2010 to January 2021. Studies were included if they described the effects of a physical exercise intervention in people with mTBI on persistent symptoms. Study quality, intervention reporting, and confidence in review findings were assessed with the CASP, TIDieR and GRADE respectively.

Results: 11 eligible studies were identified for inclusion. Study interventions broadly comprised of two categories of physical exercise, i.e., aerobic (n = 8) and vestibular (n = 3). A meta-analysis (n = 3) revealed the aerobic exercise group improvement was significantly larger compared to the usual care group -0.39 (95% CI: -0.73 to -0.05, p = 0.03). Only three studies using vestibular exercise reported on persistent symptoms and yielded mixed results.

Conclusions: This study demonstrated that the use of aerobic exercise is supported by mixed quality evidence and moderate certainty of evidence, yet there is limited evidence for the use of vestibular exercise for improving persistent symptoms in people with mTBI.

[Abstract] The role of psychological flexibility in recovery following mild traumatic brain injury

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Cognitive Rehabilitation, TBI on March 21, 2022

Abstract

Purpose and Objective: Psychological distress is known to contribute to recovery following mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) and there is a need to understand the mechanisms that contribute to this relationship. The present study examined psychological flexibility, as a hypothesized psychological mechanism, in 169 treatment-seeking adults with mTBI. Research Method/Design: Participants completed self-report measures of postconcussion symptoms, psychological distress (anxiety, stress, and depression) and functional status within four weeks of entry to an mTBI outpatient clinic. A general measure (Acceptance and Action Questionnaire), as well as a context-specific (Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-Acquired Brain Injury) measure of psychological flexibility were administered.

Results: Simple linear regression analysis showed that psychological flexibility made a significant contribution to the prediction of postconcussion symptoms and functional status. A series of multiple mediation analyses also found that psychological flexibility had a significant indirect effect on the relationships between psychological distress and postconcussion symptoms, and functional status. The context-specific, rather than the general measure of psychological flexibility, was consistently shown to contribute to these findings.

Conclusions/Implications: These results suggest that psychological flexibility is a psychological mechanism that contributes to recovery outcomes in individuals with mTBI and could therefore be an important treatment target in mTBI interventions. (PsycInfo Database Record (c) 2021 APA, all rights reserved).

Similar articles

- Psychological flexibility: A psychological mechanism that contributes to persistent symptoms following mild traumatic brain injury?Faulkner JW, Theadom A, Mahon S, Snell DL, Barker-Collo S, Cunningham K.Med Hypotheses. 2020 Oct;143:110141. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.110141. Epub 2020 Jul 30.PMID: 32759012

- Association of Sex and Age With Mild Traumatic Brain Injury-Related Symptoms: A TRACK-TBI Study.Levin HS, Temkin NR, Barber J, Nelson LD, Robertson C, Brennan J, Stein MB, Yue JK, Giacino JT, McCrea MA, Diaz-Arrastia R, Mukherjee P, Okonkwo DO, Boase K, Markowitz AJ, Bodien Y, Taylor S, Vassar MJ, Manley GT; TRACK-TBI Investigators, Adeoye O, Badjatia N, Bullock MR, Chesnut R, Corrigan JD, Crawford K, Dikmen S, Duhaime AC, Ellenbogen R, Feeser VR, Ferguson AR, Foreman B, Gardner R, Gaudette E, Gonzalez L, Gopinath S, Gullapalli R, Hemphill JC, Hotz G, Jain S, Keene CD, Korley FK, Kramer J, Kreitzer N, Lindsell C, Machamer J, Madden C, Martin A, McAllister T, Merchant R, Nolan A, Ngwenya LB, Noel F, Palacios E, Puccio A, Rabinowitz M, Rosand J, Sander A, Satris G, Schnyer D, Seabury S, Sun X, Toga A, Valadka A, Wang K, Yuh E, Zafonte R.JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Apr 1;4(4):e213046. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.3046.PMID: 33822070 Free PMC article.

- Turning away from sound: The role of fear avoidance in noise sensitivity following mild traumatic brain injury.Faulkner JW, Snell DL, Shepherd D, Theadom A.J Psychosom Res. 2021 Dec;151:110664. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2021.110664. Epub 2021 Nov 3.PMID: 34749069

- Anxiety sensitivity and alexithymia as mediators of postconcussion syndrome following mild traumatic brain injury.Wood RL, O’Hagan G, Williams C, McCabe M, Chadwick N.J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2014 Jan-Feb;29(1):E9-E17. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e31827eabba.PMID: 23381020

- Characteristics of patients included and enrolled in studies on the prognostic value of serum biomarkers for prediction of postconcussion symptoms following a mild traumatic brain injury: a systematic review.Mercier E, Tardif PA, Emond M, Ouellet MC, de Guise É, Mitra B, Cameron P, Le Sage N.BMJ Open. 2017 Sep 27;7(9):e017848. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017848.PMID: 28963310 Free PMC article. Review.

[WEB PAGE] Progesterone Effective in Speeding Recovery From TBI?

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Pharmacological, REHABILITATION, TBI on April 2, 2021

Progesterone Effective in Speeding Recovery From TBI?

Batya Swift Yasgur, MA, LSW – March 31, 2021

Progesterone may have a protective effect against the impact of mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) in female athletes when the injury takes place during the phase of the menstrual cycle (MC), when progesterone levels are highest, early research suggests.

“Our findings suggest being in the luteal phase (right after ovulation) of the menstrual cycle when progesterone is highest — or being on contraceptives, which artificially increase progesterone — may mean athletes won’t have as severe symptoms when they have a concussion injury,” study investigator Amy Herrold, PhD, research assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, said in a press release.

The study was published online February 24 in the Journal of Neurotrauma.

Research Gap

“Our group has been working together toward looking at neuroimaging and potential biomarkers for mTBI or concussion in athletes,” Herrold told Medscape Medical News.

“When we started looking at the literature, we began to see a real gap to be filled, specifically studying female athletes, since a lot of concussion sports literature focused on males and also didn’t focus on female-specific factors such as hormonal menstrual cycle levels or hormonal contraceptives,” she added

College athletics are divided into two categories — varsity and club — and, although there are many more club than varsity athletes (> 2 million vs 460,000), most research has been conducted in varsity athletes.

“This is important because the sports participation of club athletes is less tightly regulated, compared to varsity athletes,” she said.

In addition, previous research suggests gonadal hormones, in particular progesterone, have “widespread non-reproductive functions in the central nervous system (CNS) and have neuroprotective effects in various disorders,” including TBI, the authors write.

“These putative neuroprotective effects emphasize the importance of considering MC phase when mTBI occurs,” the authors note.

In addition, some research has suggested that users of hormonal contraceptives (HC) have lower postconcussive symptom severity, compared to non-HC users — in particular, better cognitive performance after injury.[…]

[Abstract] Satisfaction with Life after Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: A TRACK-TBI Study

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Caregivers, TBI on December 23, 2020

Abstract

Identifying the principal determinants of life satisfaction following mild TBI (mTBI) may inform efforts to improve subjective well-being in this population. We examined life satisfaction among participants in the Transforming Research and Clinical Knowledge in Traumatic Brain Injury (TRACK-TBI) study who presented with mTBI (Glasgow Coma Scale [GCS] score = 13–15; n = 1152). An L1-regularization path algorithm was used to select optimal sets of baseline and concurrent symptom measures for prediction of scores on the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) at 2 weeks and 3, 6, and 12 months post-injury. Multi-variable linear regression models (all n = 744–894) were then fit to evaluate associations between the empirically selected predictors and SWLS scores at each follow-up visit. Results indicated that emotional post-TBI symptoms (all b = −1.27 to −0.77, all p < 0.05), anhedonia (all b = −1.59 to −1.08, all p < 0.01), and pain interference (all b = −1.38 to −0.89, all p < 0.001) contributed to the prediction of lower SWLS scores at all follow-ups. Insomnia predicted lower SWLS scores at 2 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months (all b = −1.11 to −0.83, all ps < 0.01); and negative affect predicted lower SWLS scores at 2 weeks, 3 months, and 12 months (all b = −1.38 to −0.80, all p < 0.005). Other post-TBI symptom domains and baseline socio-demographic, injury-related, and clinical characteristics did not emerge as robust predictors of SWLS scores during the year after mTBI. Efforts to improve satisfaction with life following mTBI may benefit from a focus on the detection and treatment of affective symptoms, pain, and insomnia. The results reinforce the need for tailoring of evidence-based treatments for these conditions to maximize efficacy in patients with mTBI.

[BLOG POST] Brain Injury Overview – CNS

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in TBI on September 25, 2020

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) can significantly affect many cognitive, physical, and psychological skills. Physical deficit can include ambulation, balance, coordination, fine motor skills, strength, and endurance. Cognitive deficits of language and communication, information processing, memory, and perceptual skills are common. Psychological status is also often altered. Adjustment to disability issues are frequently encountered by people with TBI.

Brain injury can occur in many ways. Traumatic brain injuries typically result from accidents in which the head strikes an object. This is the most common type of traumatic brain injury. However, other brain injuries, such as those caused by insufficient oxygen, poisoning, or infection, can cause similar deficits.

Mild Traumatic Brain Injury (MTBI) is characterized by one or more of the following symptoms: a brief loss of consciousness, loss of memory immediately before or after the injury, any alteration in mental state at the time of the accident, or focal neurological deficits. In many MTBI cases, the person seems fine on the surface, yet continues to endure chronic functional problems. Some people suffer long-term effects of MTBI, known as postconcussion syndrome (PCS). Persons suffering from PCS can experience significant changes in cognition and personality.

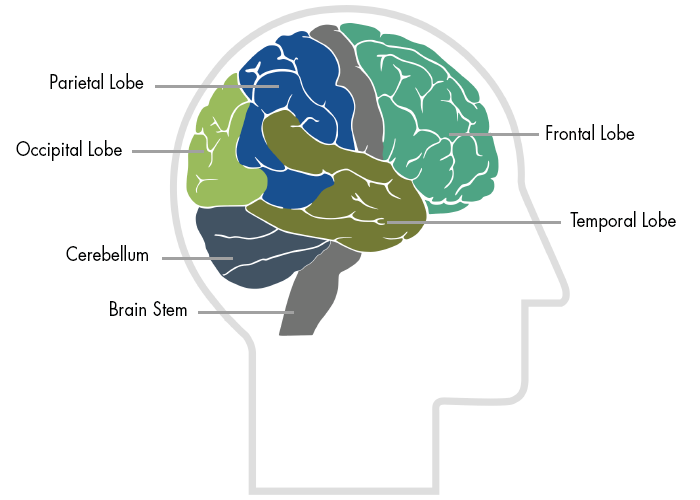

Most traumatic brain injuries result in widespread damage to the brain because the brain ricochets inside the skull during the impact of an accident. Diffuse axonal injury occurs when the nerve cells are torn from one another. Localized damage also occurs when the brain bounces against the skull. The brain stem, frontal lobe, and temporal lobes are particularly vulnerable to this because of their location near bony protrusions.

The brain stem is located at the base of the brain. Aside from regulating basic arousal and regulatory functions, the brain stem is involved in attention and short-term memory. Trauma to this area can lead to disorientation, frustration, and anger. The limbic system, higher up in the brain than the brain stem, helps regulate emotions. Connected to the limbic system are the temporal lobes which are involved in many cognitive skills such as memory and language. Damage to the temporal lobes, or seizures in this area, have been associated with a number of behavioral disorders. The frontal lobe is almost always injured due to its large size and its location near the front of the cranium. The frontal lobe is involved in many cognitive functions and is considered our emotional and personality control center. Damage to this area can result in decreased judgement and increased impulsivity.

Conditions and Other Information

- anoxia and hypoxia

- aphasia

- biomechanics of brain injury

- cognitive and communication disorders

- coma

- concussion

- cure for brain injury

- epidemiology of traumatic brain injury

- sexual dysfunction

- traumatic brain injury recovery

- traumatic brain injury statistics

- what is the prognosis for traumatic brain injury

- vision problems

[Booklet] Recovering from Mild Traumatic Brain Injury/Concussion – PDF File

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Caregivers, REHABILITATION, TBI on September 22, 2020

Guide for Patients and Their Families

This booklet provides a few answers to questions commonly asked by patients and family members following a mild traumatic brain injury (TBI) which is also called a concussion. It describes some of the problems that people may experience after a mild TBI and offers some tips on coping with these problems. As you read this booklet, keep in mind that everyone recovers a little bit differently. Everyone improves after a mild TBI, and most people recover completely in time. We hope that you find this booklet helpful.[…]

[Abstract] Gait Performance in People with Symptomatic, Chronic Mild Traumatic Brain Injury

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Gait Rehabilitation - Foot Drop, TBI on September 18, 2020

Abstract

There is a dearth of knowledge about how symptom severity affects gait in the chronic (>3 months) mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) population despite up to 53% of people reporting persisting symptoms after mTBI. The aim of this investigation was to determine whether gait is affected in a symptomatic, chronic mTBI group and to assess the relationship between gait performance and symptom severity on the Neurobehavioral Symptom Inventory (NSI). Gait was assessed under single- and dual-task conditions using five inertial sensors in 57 control subjects and 65 persons with chronic mTBI (1.0 year from mTBI). The single- and dual-task gait domains of Pace, Rhythm, Variability, and Turning were calculated from individual gait characteristics. Dual-task cost (DTC) was calculated for each domain. The mTBI group walked (domain z-score mean difference, single-task = 0.70; dual-task = 0.71) and turned (z-score mean difference, single-task = 0.69; dual-task = 0.70) slower (p < 0.001) under both gait conditions, with less rhythm under dual-task gait (z-score difference = 0.21; p = 0.001). DTC was not different between groups. Higher NSI somatic subscore was related to higher single- and dual-task gait variability as well as slower dual-task pace and turning (p < 0.01). Persons with chronic mTBI and persistent symptoms exhibited altered gait, particularly under dual-task, and worse gait performance related to greater symptom severity. Future gait research in chronic mTBI should assess the possible underlying physiological mechanisms for persistent symptoms and gait deficits.

Source: https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/abs/10.1089/neu.2020.6986