Archive for January, 2024

[BLOG POST] Inpatient and outpatient discharge: your top questions answered

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Caregivers on January 30, 2024

One of the hardest questions for either a client or a clinician to answer is “When am I done with therapy?” Read on to check out some useful tricks and tips – and lots of questions answered! – for patients and clinicians alike to make sure that the discharge process is smooth and leaves everyone feeling confident about next steps.

What does “discharge” mean and how does it differ across settings (inpatient and outpatient)?

Discharge, or completing treatment within a specific setting or from a specific healthcare provider, is a tricky process across settings, and is impacted by so many factors. First, let’s define the process a bit.

Here are the major settings that we might be talking about getting discharged FROM. Keep in mind, this is not a straight linear model – a patient may move between these various settings throughout their journey.

In-patient Acute Care Hospital – first off, defining these settings can be tough, because they have some overlapping terminology – here I’m referring to the hospital, where a patient might have been admitted after going to the emergency department with signs of a stroke or after a traumatic brain injury.

- Who leads the discharge decision? Generally, it’s a team decision across medical providers.

- Who makes the discharge plan? Often this is completed by a case manager, who may be a nurse or social worker who has strong connections to the community and can make sure that the patient is off to the next appropriate setting for them.

- When is the patient ready for discharge? In the hospital setting, usually this is determined by medical stability and safety – doctors want you to be able to get home as soon as possible, while making sure that you’re safe to move to your next setting, wherever that might be.

- What’s next? That depends on the individual patient. Some patients may be ready to go straight home with a referral for outpatient or home health therapy. Some patients might need to get stronger and more independent in a skilled nursing facility. Other patients might be ready for and need the intensive therapy that a long-term acute care hospital (an LTACH) can provide.

In-patient Long-Term Acute Care Hospital (LTACH) – these are specially designed hospitals for patients who need intensive therapy to help them recover, like speech, occupational, and/or physical therapy for about a month or more. Patients who are a good fit for an LTACH can tolerate three or more hours of intense therapy a day.

- Who leads the discharge decision? This is also usually a team decision across medical providers, including physicians and therapists, as well as the patient and their caregivers.

- Who makes the discharge plan? Again, this is often completed by a case manager in collaboration with the rest of the care team.

- When is the patient ready for discharge? This depends on the progress that a patient made, and the therapy team’s confidence in their ability to maintain that progress and demonstrate their independence in whatever setting is next for them.

- What’s next? Again, this is patient dependent. Sometimes a patient might move from an LTACH to a skilled nursing facility if they’re not quite ready for home. Other times, a patient might go directly home from an LTACH, with referrals in place for continued outpatient or home health therapy as needed.

Skilled Nursing Facility (SNF) – a skilled nursing facility is a great fit for a patient who may not need or may not be quite ready for the intensity of an LTACH, but isn’t quite ready to be back home.

- Who leads the discharge decision? Again, a team decision is made by medical providers, but also by the patient and their caregivers to ensure that the patient will be safe when heading home.

- Who makes the discharge plan? Also a team process, generally led by a case or care manager.

- When is the patient ready for discharge? If a patient is being discharged to go home, the biggest question is whether they are ready to be home with whatever level of support is available to them. Can they safely use the restroom on their own? Can they safely prepare meals? Can they manage their finances with the support they have available? Occupational therapists are essential team members in making these decisions, because functional application of activities of daily living is their expertise.

- What’s next? Often a patient will head home after being in a SNF, or move in with a family member or other loved one. They might continue to get support within the home, or they might transition to outpatient therapy.

Outpatient or Home Health – if the patient is medically able to be safely transported to an outpatient clinic or private practice, they might continue their therapy there. Some outpatient clinics are a part of a hospital group, while some are private, stand-alone clinics or practices. If a patient is unable to leave the home for medical reasons, they may qualify for home health services, where the providers come to the patient to deliver therapy right in their home.

- Who leads the discharge decision? This is a team decision between the therapists, the patient, their caregivers, and sometimes primary care providers.

- Who makes the discharge plan? Usually a therapist will provide patients with discharge summaries and paperwork, which the patient and therapist can create together.

- When is the patient ready for discharge? While it may not be realistic for a patient to get back to baseline, or their ability levels before their stroke or brain injury, they may achieve the goals that they and their therapist set out at the start of therapy. Another important thing to keep in mind is that sometimes, breaks from therapy can be helpful for patients. Therapy is hard work, and it’s important to check in from time to time to see if a break might be beneficial.

- What’s next? It’s important for patients to make sure they know what tasks and tools they should be utilizing in their everyday lives to make sure they maintain all the great progress they made in therapy. Patients and loved ones should also be educated on red flags that suggest that they should call their therapist to see if they might need a check-in.

**Tough but important topic to mention here: in the US, sometimes the unfortunate and uncomfortable reality is that insurance coverage plays a role in these decisions. Make sure as a caregiver or patient that you ask your discharge team about insurance coverage and what to expect. Call your insurance company and ask them what they will and won’t cover during your recovery. I won’t lie to you – it is a convoluted and challenging process. But it’s important to be an informed consumer, and the earlier you know, the better prepared you can be to cope and fight as needed.

Factors that impact discharge

A lot of components come into play when deciding whether a patient is ready to be discharged from a setting or provider:

- Medical stability – is the patient medically safe and ready to move on to a different setting or type of therapy?

- Independence – is the patient able to operate independently enough to be safe with the level of support available to them in their next setting

- Generalization – has the patient learned how to apply the skills they’ve learned in therapy across environments?

Many factors can also speed up or slow down progress to discharge, such as:

- Severity of the issue that you are being treated for

- Other medical factors & setbacks

- Frequency of visits, consistency of attendance, and participation in therapy – this includes not only how many times per week or month a patient receives therapy, but also how consistently they make it to their appointments, ready to get to work; if you as a patient or a caregiver are having trouble physically making it to your appointments, reach out to your clinician early to brainstorm solutions.

- Ability to practice skills outside of treatment time – a patient’s practice can’t start and end as they walk in or out of a PT, OT or SLP session; if you’re a clinician looking for evidence-based homework you can easily track, check out Constant Therapy Clinician as a tool to manage your patients’ home practice programs; if you’re a patient or a caregiver, ask your clinician for homework to carry over your skills outside of therapy.

What can I do to make the discharge process smooth as a patient?

- Make your priorities known – tell your therapist what’s most important to you and remind them early and often. Excited to read stories to your grandchildren? Your therapist will be thrilled to help you work towards that goal!

- Ask for practice activities – practice makes progress! Don’t limit yourself to working on your goals only during therapy – ask your therapist for tools and tips to continue that practice at home on your own time. Just a few minutes a day can make a HUGE difference. A study actually showed recently that when patients used Constant Therapy at home in addition to during sessions with their clinicians, they got MORE THAN FOUR TIMES the amount of practice!! That adds up and results in incredible progress.

- Do the work – show up to therapy on time and ready to go, whenever you possibly can! Therapists understand that there can be many barriers to making it to therapy – if you’re having trouble, make sure to talk with your therapist early so you can troubleshoot together.

- Take care of yourself – recovering from a brain injury or stroke, or learning to live with a new neurological disorder is an incredibly taxing experience physically, emotionally, and mentally, both for a patient and for their loved ones. Take time to recognize those struggles and seek help from mental health providers. Give yourself grace and space to recover, adjust, and find your newly defined identity.

What can I do to make the discharge process smooth as a provider?

- Have the tough talks early – have an honest conversation with your patients early in their treatment about what they would consider a “successful outcome”. Sometimes we have to help our patients set realistic goals in the face of a completely altered life plan, and these conversations, while challenging, are essential for patients emotionally and mentally.

- Collaboratively write goals – by using patient-centered planning models, such as the Life Participation Approach to Aphasia, we can work as a team with patients and their families to define goals that are important to them, clearly stated, and thus all the more motivating.

- Track progress – there’s nothing more motivating for patients than reviewing the goals you wrote together and seeing how far they’ve come. I love to involve patients in the tracking process by asking them to rate their independence on a specific skill frequently throughout our therapy process. Constant Therapy’s progress tracking tools are also hugely helpful in reviewing concrete, data-driven speech therapy progress.

- Make discharge planning collaborative – this is especially applicable in outpatient therapy, but for many patients feeling involved in the discharge decision process is incredibly empowering. When a life altering event like a stroke, TBI, or new neurological diagnosis occurs, a patient can feel that they’ve lost power, as do their caregivers.

- Build in a safety net – often I’ve found that making patients aware that they can always give me a call, send me an email, etc. to see if they need to return to therapy can be very comforting. Just the knowledge that I, or another therapist, will always be here to back them up is incredibly powerful.

Finally, empower patients with tools for maintenance and continued recovery – as a clinician, giving your patients instructions on how to continue and maintain their progress on their own is hugely helpful. Constant Therapy is a great way to do just that – our program will continue to challenge your patients using our NeuroPerformance Engine, which adjusts patient tasks based on their performance. We also have a handy Discharge Summary within our Clinician Web Dashboard, that provides your patient with a summary of their progress within Constant Therapy and instructions on how to get set up with Constant Therapy at home.

[Abstract] Current and future utility of ultrasound imaging in upper extremity musculoskeletal rehabilitation: A scoping review

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Paretic Hand, Radiology/Imaging technology on January 30, 2024

Highlights

- •Sonography is used to examine a range of UE conditions, structures, and etiologies.

- •Sonography demonstrates preliminary utility in UE rehabilitation and research.

- •A large body of knowledge is available to inform innovative clinical applications.

- •Further research is needed to determine specific clinical efficacy and impact.

Abstract

Background

Continued advances in musculoskeletal sonography technology and access have increased the feasibility of point-of-care use to support day-to-day clinical care and decision-making. Sonography can help improve therapeutic outcomes in upper extremity (UE) rehabilitation by enabling clinicians to visualize underlying structures during treatment.

Purpose of the Study

This study aimed to (1) evaluate the growth, range, extent, and composition of sonography literature supporting UE rehabilitation; (2) identify trends, gaps, and opportunities with regard to anatomic areas and diagnoses examined and ultrasound techniques used; and (3) evaluate potential research and practice utility.

Methods

Searches were completed in PubMed, CINAHL, SPORTDiscus, PsycINFO, and BIOSIS. We included data-driven articles using ultrasound imaging for upper extremity structures in rehabilitation-related conditions. Articles directly applicable to UE rehabilitation were labeled direct articles, while those requiring translation were labeled indirect articles. Articles were further categorized by ultrasound imaging purpose. Article content between the two groups was descriptively compared, and direct articles underwent an evaluation of evidence levels and narrative synthesis to explore potential clinical utility.

Results

Average publication rates for the final included articles (n = 337) steadily increased. Indirect articles (n = 288) used sonography to explore condition etiology, assess measurement properties, inform medical procedure choice, and grade condition severity. Direct articles (n = 49) used sonography to assess outcomes, inform clinical reasoning, and aid intervention delivery. Acute UE conditions and emerging sonography technology were rarely examined, while tendon, muscle, and soft tissue conditions and grayscale imaging were common. Rheumatic and peripheral nerve conditions and Doppler imaging were more prevalent in indirect than direct articles. Among reported sonography service providers, there was a high proportion of nonradiologist clinicians.

Conclusion

Sonography literature for UE rehabilitation demonstrates potential utility in evaluating outcomes, informing clinical reasoning, and assisting intervention delivery. A large peripheral knowledge base provides opportunities for clinical applications; however, further research is needed to determine clinical efficacy and impact for specific applications.

[…]

[Abstract] Exergames as a rehabilitation tool to enhance the upper limbs functionality and performance in chronic stroke survivors: a preliminary study

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Paretic Hand, REHABILITATION, Video Games/Exergames on January 30, 2024

Post-stroke hemiplegia commonly occurs in stroke survivors, negatively impacting the quality of life. Despite the benefits of initial specific post-acute treatments at the hospitals, motor functions and physical mobility need to be constantly stimulated to avoid regression and subsequent hospitalizations for further rehabilitation treatments. This preliminary study proposes using gamified tasks in a virtual environment to stimulate and maintain upper limb mobility through a single RGB-D camera-based vision system (using Microsoft Azure Kinect DK). This solution is suitable for easy deployment and use in home environments. A cohort of 10 post-stroke subjects attended a 2-week gaming protocol consisting of Lateral Weightlifting (LWL) and Frontal Weightlifting (FWL) gamified tasks and gait as the instrumental evaluation task. Despite its short duration, there were statistically significant results (p < 0.05) between the baseline (T0) and the end of the protocol (TF) for Berg Balance Scale and Time Up-and-Go (9.8% and -12.3%, respectively). LWL and FWL showed significant results for unilateral executions: rate in FWL had an overall improvement of 38.5% (p < 0.001) and 34.9% (p < 0.01) for the paretic and non-paretic arm, respectively; similarly, rate in LWL improved by 19.9% (p < 0.05) for the paretic arm and 29.9% (p < 0.01) for non-paretic arm. Instead, bilateral executions had significant results for rate and speed: considering FWL, there was an improvement in rate with p < 0.01 (31.7% for paretic arm and 37.4% for non-paretic arm), whereas speed improved by 31.2% (p < 0.05) and 41.7% (p < 0.001) for the paretic and non-paretic arm, respectively; likewise, LWL showed improvement in rate with p < 0.001 (29.% for paretic arm and 27.8% for non-paretic arm) and in speed with 23.6% (p < 0.05) and 23.5% (p < 0.01) for the paretic and non-paretic arms, respectively. No significant results were recorded for gait task, although an overall good improvement was detected for arm swing asymmetry (-22.6%). Hence, this study suggests the potential benefits of continuous stimulation of upper limb function through gamified exercises and performance monitoring over medium-long periods in the home environment, thus facilitating the patient’s general mobility in daily activities.

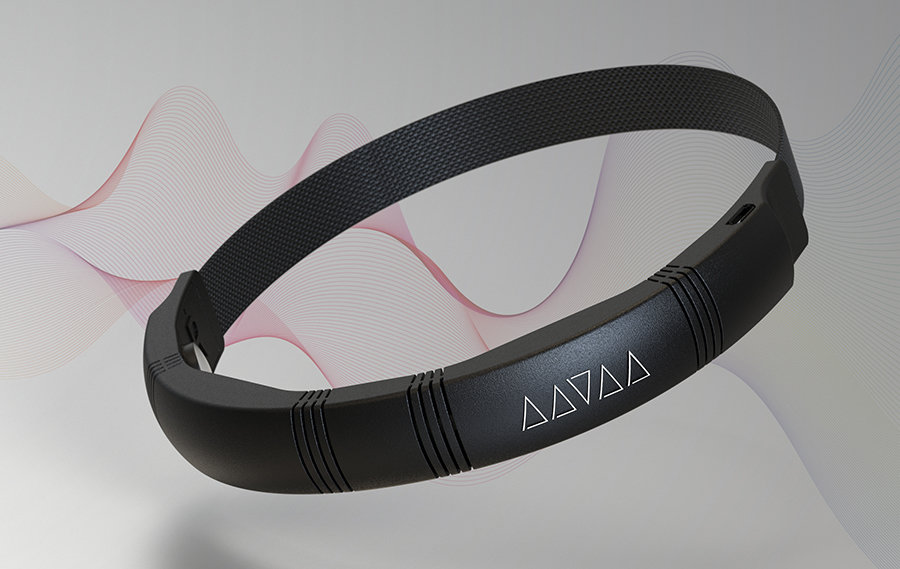

[WEB] The power of brain-computer interface assistive devices for motor impairments

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Assistive Technology on January 29, 2024

Naeem Komeilipoor, CTO of AAVAA, discusses how brain-computer interface assistive devices are working to overcome the limitations of current assistive products, and how these devices enable users with motor impairments to operate devices without difficult physical or spoken commands.

In a world that celebrates technological innovation and connectivity, it is vital to remember that not everyone enjoys the same level of access to these benefits. Globally, more than 2.5 billion people require assistive products to overcome mobility impairments and speech communication disorders, according to data from the World Health Organization (WHO). These individuals often face significant challenges in their daily lives, struggling to communicate effectively and engage with the modern, technologically advanced world.

Brain-computer interface technology has undergone a remarkable transformation over the years and is, among other things, providing a long-awaited solution to those with motor impairments. These devices are used to provide functionality to paralysed people, control devices without difficult physical or spoken demands, create the controller of the future for AR/VR environments, and even change how astronauts function in space.

In the ever-evolving landscape of accessibility technology, brain-controlled assistive devices are poised to make a significant impact, offering newfound independence and capabilities to individuals facing motor and speech-related challenges in areas such as enabling paralysed individuals to steer their wheelchairs, operate household appliances, and much more. They are ushering in an era where interaction transcends traditional physical and verbal constraints and radically transforms the daily life of these individuals.

Understanding the types of impairments

To comprehend the significance of brain-controlled assistive devices, it is essential to first define the two primary categories of motor impairments they address:

- Complete mobility impairments and paralysis. This category encompasses individuals with a diverse range of conditions, including cerebral palsy, spinal cord injuries, quadriplegia, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and even those who maintain control over their eye and/or facial movements, allowing for subtle gestures or slight head movements. While some may retain limited motor skills, their movement is significantly restricted, often requiring assistance with daily activities.

- Speech communication disorders with motor impairments. People in this category not only struggle with mobility but also face challenges in speech communication, including conditions such as the locked-in syndrome, neurodegenerative disorders such as cerebral palsy, and those with spinal cords and traumatic brain injuries. Existing assistive technologies fall short in providing comprehensive solutions for them.

Both categories share common problems, including their reliance on assistance for tasks most take for granted and limitations in current assistive technologies.

Existing challenges in assistive technologies

Current assistive technologies, although invaluable, have limitations that impact the quality of life for individuals with motor impairments and speech communication disorders. These challenges include:

- Limited interaction – Many assistive technologies are unable to seamlessly interact with other devices, leading to dependence on caregivers, nurses, or personal assistants for even basic tasks.

- Single device interaction – Users often struggle with the inability to interact with multiple devices simultaneously, limiting their independence and productivity.

- Eye-tracking inefficiencies – Eye-tracking technology, a common solution, suffers from inefficiencies. It requires periodic calibration and often relies on infrared light, making it sensitive to various lighting conditions, including bright sunlight. Additionally, it may not work effectively for individuals with smaller or less distinct eye features, further limiting its reliability as an assistive solution.

- Gesture recognition – Distinguishing between intentional gestures, like blinks or slight, involuntary head movements, and unintentional ones remains a challenge, often resulting in misunderstandings and causing frustration among users.

A new, innovative solution for motor impairments: Brain-computer interface assistive devices

Brain-computer interface (BCI) assistive devices are working to overcome the limitations of current assistive products. BCI assistive devices translate brain and bio-signals directly into meaningful commands for devices.

For the first time, users with motor impairments can operate devices without difficult physical or spoken commands. The technology decodes a user’s eye movements, as well as their intentions and subtle commands, including blinks, winks, tongue movements, and more.

A real-world application showcasing the power of this technology is the AAVAA Headband. This groundbreaking wearable device uniquely operates as a ‘head mouse’ capable of deciphering a user’s head and eye movements, as well as their intentions and subtle commands. This capability empowers users to manage various devices, like phones, tablets, or assistive tools, with straightforward actions like a blink, thereby reshaping accessibility for individuals with limited motor function.

BCI assistive devices empower users to interact with multiple devices simultaneously, fostering independence and efficiency. These devices remain unaffected by varying lighting conditions and exhibit the capability to accurately distinguish between intentional and unintentional gestures, thanks to their reliance on physiological cues and advanced algorithms.

They have the potential to transform the lives of individuals with motor impairments and speech communication disorders in numerous ways:

- Environmental control – Brain-controlled devices enable users to effortlessly manage their home environment through intuitive eye, blink, and head commands, enhancing daily living by promoting independence and comfort. Tasks include muting the TV, adjusting smart home devices, like speakers, or dimming the lights.

- Communication enhancement – These innovative technologies enable individuals with speech disorders to communicate fluidly by typing and speaking through simple head and eye movements, which not only strengthens their social connections but also results in significant enhancements in healthcare communication with providers. This breakthrough diminishes the necessity for intermediaries, ultimately promoting greater independence and improving the overall quality of care for these individuals.

- Mobility enhancement – BCI devices further expand their functionalities to include wheelchair control, granting individuals with physical disabilities greater mobility and independence in their everyday activities, whether it’s running errands or engaging in social interactions.

BCI sensors have the remarkable ability to blend information from the environment, brain, and body using only a hearable device. This comprehensive data collection goes beyond improving health and well-being; it offers a unique insight into one’s physiological state, potentially revolutionising healthcare practices.

Additionally, we can consider as applications of BCI technology:

- Health monitoring: BCI devices can monitor trauma and sudden movements and even fall detection, helping caregivers and medical professionals provide timely assistance. These devices can also track stress, fatigue, and heart rate, enabling more effective health management and enhancing overall well-being.

- Supporting health and social care professionals: Through the use of BCI devices, social workers can continuously monitor patients without hindering their movements or causing distractions, improving support and care.

These devices are available to users in a variety of form factors, such as hardware and earpieces, including earbuds, headphones, glasses, and headbands. The emphasis on ergonomic and user-friendly design ensures that these devices are seamlessly integrated into daily life, offering not only advanced functionality but also comfort and accessibility.

The advent of brain-computer interface assistive devices represents a beacon of hope for individuals with motor impairments and speech communication disorders. These technologies can significantly enhance their quality of life by addressing the limitations of existing solutions.

As the field of assistive technology continues to advance, we can look forward to even more transformative innovations like BCI technology that empower those in need while also making it easier for health and social care professionals to do their jobs more efficiently.

[WEB] Understanding Behavior Changes after TBI – Factsheets

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Caregivers, TBI on January 29, 2024

What are some possible behavior changes?

People who have a moderate or severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) may have changes in their behavior. People with a TBI and their families encounter some common behaviors:

- Problems managing emotions. People with a TBI may have a sudden change in mood; they also may have an extreme emotional response to a situation. They may raise their voice, cry, or laugh.

- Restlessness. People with a TBI may fidget, pace, or move in a repetitive way. For example, they may sway at an unusual pace.

- Problems with social behavior. People with a TBI may avoid others, interrupt others, or say things that do not fit the situation or are hurtful. They also may make sexually inappropriate comments.

- Refusing to do things. People with a TBI may say “no” to doing something, such as going to therapy or doing other activities.

- Feeling unmotivated. People with a TBI may have difficulty engaging in an activity even though they know the benefit of doing it or why it needs to be done. This is not caused by fatigue or laziness.

- Difficulty starting tasks. People with a TBI may have trouble starting tasks or conversations, even if these are things they want to do.

Who is at risk for behavior changes?

Behavior changes (also called personality changes) are common for people with a moderate or severe TBI. These changes often occur soon after the TBI and may change across time. The types of changes people have and how long they last depend on where their injury is, how severe it is, and other factors. People with a severe TBI are more likely to have behavior changes that last for a while. The good news is that behavior changes can get better as time passes.

This factsheet talks about why changes in behavior happen. It also includes tips for what to do when problem behaviors occur. It includes a framework that people with a TBI, their families, and others can use to help manage changes in behavior caused by TBIs.

Why do changes in behavior happen?

Changes in behavior after TBI happen for many reasons, including changes in the way the brain works. The following are some of the most common changes.

- Some people with a TBI may have problems with focusing, thinking, or communicating. They also may have issues with how long it takes to process information and respond to it. These issues can make it hard to keep up with a conversation or understand a situation. As a result, people with a TBI may appear to be uncooperative. They also may appear “off-task” or out of sync with what is happening in a fast-paced situation. They may avoid social situations because they feel uncomfortable or embarrassed when they are with other people.

- People with a TBI may have problems with thinking skills. These problems may make it hard for them to understand why some things happen or what to do when they happen. This can make the person feel irritated, refuse to do things, or not do things that they agreed to do. They also may have a hard time making choices.

- People with a TBI may have poor impulse control. This can make it hard for them to filter their thoughts or actions. They may not think about or understand the effect of what they say or do before they say or do something inappropriate or unsafe.

- People with a TBI may not be fully aware of their current issues. This can cause them to refuse to use a walker or wheelchair. They also may refuse to take part in therapy. Some people with a TBI may not follow recommendations or restrictions that are meant to help them be independent, keep them safe, and help them recover.

- Keep in mind that people with a TBI cannot always control their behavior, which is especially true in situations that are highly stressful. The A-B-C framework discussed later in this factsheet includes strategies to help people with a TBI prevent problem behaviors. If the behavior does occur, the framework includes techniques to distract the person or help them relax.

- People with a TBI often have an emotional response to their injury. They may feel a sense of loss because of less independence, changes to their role within the family, and a lack of control over their situation. The following factsheets may help in these situations (see Depression after TBI; Relationships After TBI, Emotional Problems After TBI; Understanding and Coping With Irritability, Anger, and Aggression After TBI). The following sections address problem behaviors.

What can I do to identify problem behaviors?

Identify problem behaviors

The goal of the A-B-C framework is to keep the problem behavior (the “B”) from occurring. Other strategies involve changing the things that happen after a behavior occurs, which can help change how intense, severe, or frequent the behavior is.

- The first step is to identify the behavior. Make a list of behaviors that you see that are a problem.

- Work with a professional to review the list to identify the behavior(s) that need to change. Keep in mind that a specific behavior may not be a problem to everyone. Ask family and friends for their input.

- Update the list as new behaviors come up and old ones are no longer a problem.

Follow the A-B-C approach to better understand problem behaviors

The A-B-C framework can help you understand the approach a professional may use to figure out when and why a behavior or emotional response may occur. This section discusses the framework. You may have a family member or friend assist with this exercise. If you have questions, you can contact a professional with experience in managing behavior after TBI before using.

A. Antecedent. An antecedent is what happens right before the problem behavior occurs. Take notes on everything you remember; it may not be clear what the “trigger” was for the behavior. Your notes can help you find patterns. From them, you will come up with ideas about triggers or causes of the problem behavior; triggers may include pain, fatigue, noise, or light sensitivity. The following are some questions to help you identify antecedents.

- Who is or is not present before the problem behavior happens?

- Where does the problem behavior take place?

- What desired items (e.g., television, video game, cell phone) are present or absent just before the problem behavior takes place? What about undesired items?

- What events took place before the problem behavior occurred?

- What time of day does the problem behavior happen?

- Is there a root cause for the behavior? Causes such as poor sleep, a reaction to medicine, changes in schedule, and diet changes set the stage for problem behaviors throughout the day.

B. Behavior. Take a close look at the problem behavior or behaviors on your list. Make notes. Describe the problem behavior in as much detail as you can. Here are some questions to understand problem behaviors.

- What does the behavior look like?

- How often does the behavior happen?

- How long does the behavior last?

- How intense is the behavior?

C. Consequences. This is what happens right after the problem behavior occurs. Take notes on all changes you see within a few minutes of the behavior. It is not likely that things that happen several minutes, hours, or days after are causing the problem behavior. The following questions should help.

- What happened right after the problem behavior?

- How did people react?

- Did the person get something from the behavior? For example, did they get attention (either good or bad)?

- Was something taken away or avoided because of the behavior?

- Did the environment change because of the behavior? For example, did the person leave a situation or place?

RELATED FACTSHEETS

FACTSHEETS

Irritability, Anger, and Aggression After TBI

FACTSHEETS

Stress Management for TBI Caregivers

FACTSHEETS

Identify and Change Antecedents (to Prevent Problem Behavior)

Spend time identifying a list of triggers and ways to prevent a problem behavior. If you cannot avoid triggers, find ways to decrease the impact of those triggers. You can organize your notes in a chart (such as the following chart) to make it easier to track your results.

| A-B-C Plan: Changing the Antecedent (to “Prevent” Problem Behavior) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAntecedent | BBehavior | CConsequence | Ideas for Change | Results |

| Physical therapy session focused on stretching activities in a patient with limited mobility because of stiffness or physical injuries that are painful during stretching | SreamingHitting therapistRefusing physical therapy | Session ended earlyPerson with TBI returns to his or her roomFamily upsetTherapist relieved | Pain during exercises may serve as trigger.Talk with a doctor about ways to reduce pain while stretching.Add activities that make the person happy but are also therapeutic. | Decreased frequency and intensity of screaming or loud volumeTherapist less anxious working with person with TBI |

Change Consequences

Consequences can be hard to pinpoint. Some may be obvious and others not so obvious. It is helpful to use a chart to list things that may make it more or less likely that the problem behavior happens again. The following example shows how to organize a chart to help identify consequences.

| Consequences | |

| Things that may happen right after a problem behavior that might lead to it happening more often | Things that may happen right after a problem behavior that might lead to it happening less often |

| Gets other people to laugh when acting outGets more attentionGets out of doing an activity that he or she does not want to do, such as going to therapy | Sees that other people are disappointed in the behaviorThinks he or she is being naggedGets less time to hang out with friends or loved ones |

You can use an A-B-C chart when you work with experienced professionals, caregivers, or trusted friends to come up with ideas to improve behavior. If you feel stuck or need additional ideas, check with an experienced professional. Praise and access to desired activities are positive actions. These methods have a better impact on behavior change than negative actions and reactions (such as screaming or arguing as a response to a problem behavior).

| A-B-C Plan: Changing the Consequence (to encourage or discourage a problem behavior) | ||||

| A Antecedent | B Behavior | C Consequence | Ideas for change | Results/Goal |

| Does not want to do therapy | Refuses to do therapyIs verbally abusive | Gets out of doing therapy | Give the person a reward that is exciting to them, such as extra game time if they go to therapy.Let them choose from different activities that are fun and therapeutic. | More likely to do therapy |

| Forgets to take medication/forgets that medication has already been taken | Does not take medication as prescribed | Misses therapeutic dose of important medication/takes too much medication | Use pill box, phone, or calendar reminders; place pill box in easily visible location. | Improved medication compliance |

You also want to think about how to handle things that are seen as punishments. You should clearly explain the reasons and time frame for any punishments. Keep any restrictions in place for a short time. Talking about these things in detail helps avoid confusion. It also helps keep the punishment from being seen as random and unfair.

What are some realistic goals for behavior change?

- Aim to reduce the number of times that problem behaviors happen and their intensity. Do not expect to prevent all problem behaviors.

- Aim to make small changes across time. Changing behavior takes time. Do not expect changes to happen quickly.

- Focus first on behaviors that are easy to recognize and occur often. As you build your confidence and make progress changing behavior, you can focus on more challenging behaviors.

- Problem behaviors can be exhausting for everyone. Take time for yourself. Get help from others.

- As you start to see success in changing behavior, slowly reduce positive reinforcements. At first, you will likely use positive reinforcements each time you see good behavior. Your goal is to reach a point when you need to use only positive reinforcements from time to time and they are not expected every time. Using the A-B-C chart to track changes across time may be helpful.

Other tips

- Come up with a plan to address problem behavior. It should include the person with a TBI and use the A-B-C approach.

- Reward positive or good behavior often (“Catch them being good”). Avoid giving attention only when the problem behaviors occur. Do not hit or push the person with a TBI. It will not change problem behavior and may cause them to hit or push back in response.

- Come up with ideas to use when behavior problems happen. Have a plan in place that is ready to use. For example, be ready to leave a situation if you need to or bring distracting items with you. Be consistent! Your response to problem behavior should be the same each time. You should respond within a few minutes of the behavior. Behavior changes are most likely to happen when everyone involved is consistent and responses are quick.

- Do not be surprised if you notice an increase in problem behaviors at first. This is normal, not a sign that you have done something wrong or that your efforts are not working. Stick with your plan!

- Make eye contact. Speak slowly and in a normal voice. Do not touch the person without first saying why you are touching them.

- Explain changes in routine.

- Clearly end conversations. You can say, “I need to go do something else in the other room now. We’ll talk some more later.”

- You may choose to bargain for positive behavior. For example, a person with a TBI wants to go outside but they do not want to do their daily exercise. One way to bargain is to let them go outside but make sure they exercise while outside and in a certain time frame. Doing some stretching while outside may help make them want to take part in physical therapy.

- Take a deep breath to help stay calm. Problem behaviors are a result of the TBI; they are not meant to target anyone. Try not to take them personally.

- Avoid arguing. Fighting can make things worse and will not help the person calm down.

- Do not call attention to problem behavior in front of others; this may make the person with TBI feel embarrassed. Instead, use a nonverbal cue such as a head shake or time out signal. You can come up with the cue ahead of time.

- Leave the situation if you need to but only if the person is safe.”

- Be mindful of your own actions and reactions. You cannot control someone else’s behavior. Behavior tends to get better across time as the person recovers. Learn to understand what causes problem behavior. You also can model desired behavior. Be consistent.

| Sample A-B-C Chart | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAntecedantWhat was happening before? | BBehaviorWhat does the behavior look like? | CConsequenceWhat happened afterward? | Ideas for change | Results |

Authorship

Understanding Problem Behavior Changes After Moderate to Severe Traumatic Brain Injury was developed by Sean Hollis, PhD; Phillip Klebine, MA; Risa Nakase-Richardson, PhD, FACRM; Tom Novack, PhD, ABPP-CN; and Summar Reslan, PhD, ABPP-CN, in collaboration with the Model Systems Knowledge Translation Center.

Source: The content is based on research and/or professional consensus. This content has been reviewed and approved by experts from the Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems (TBIMS), funded by the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research, as well as experts from the Polytrauma Rehabilitation Centers (PRC), funded by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

Disclaimer: This information is not meant to replace the advice of a medical professional. You should consult your health care provider regarding specific medical concerns or treatment. The contents of this factsheet were developed under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90DP0082 and 90KPKT0009). NIDILRR is a center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this factsheet do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the federal government.

Copyright © 2021 Model Systems Knowledge Translation Center (MSKTC). May be reproduced and distributed freely with appropriate attribution. Prior permission must be obtained for inclusion in fee-based materials.

[WEB] Understanding and Coping With Irritability, Anger, and Aggression After TBI – Factsheets

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Caregivers, TBI on January 28, 2024

What are irritability, anger, and aggression and how can you recognize them?

- Irritability is an emotional state in which a person has a short temper and is easily annoyed or angered. As a result, small things can lead to harsh reactions (for example, snapping at family or friends). This is most likely to happen if the person does not know how to manage their feelings or if the person is stressed. People may feel tense, uptight, touchy, or on edge when they are irritable.

- Anger is an emotion. It’s a strong feeling of annoyance or displeasure. Sometimes angry emotions can get intense and feel out of one’s control. Anger can lead to aggressive acts. When angry, people may feel tension in their forehead, jaw, shoulders, or fists. They may feel their heart beat faster and their bodies may feel hot.

- Aggression is a type of behavior. It is often an expression of anger. Actions can range from mildly aggressive to extremely aggressive. Aggression can be hurtful comments—what you say and how you say it. It may include insults, cursing, or yelling. On the more extreme and less common end, it can include acts of violence, such as throwing things or hitting someone or something. Aggression may include other threatening actions meant to cause fear or displeasure, such as following a driver on the highway to intimidate them or refusing to do something your loved one wants to do.

- As shown below, irritability, anger, and aggression are not the same, but they can overlap or occur together. However, each can also happen on their own. For instance, someone could feel angry but not act aggressively, or someone could get angry without being irritable. Tips for managing these emotions and behaviors are presented below.

What changes can be expected after a TBI?

Feeling irritable or angry from time to time is common for most people, but a TBI may cause changes that make these feelings more of a problem.

- Irritability and anger are more common in people with TBI than they are in people without TBI. Some research shows that up to three-fourths of people with TBI have irritability. In addition, up to 50% of people with TBI have problems with anger. A person who was not prone to irritability or anger before their TBI may now be easily irritated or angered after their TBI.

- Irritability and anger after TBI can be sudden and unpredictable. After a TBI, feelings of irritability and anger can occur suddenly and ramp up quickly. These feelings may be triggered more easily than before the TBI. They may also be hard to predict.

- Anger and aggression can lead to behaviors that are difficult to control after a TBI. A TBI can make it hard for a person to talk in a respectful way about things that make him/her angry or frustrated. The person may also find it hard to stop an aggressive response, such as shouting, saying mean things, or cursing. Sometimes, they may express anger through physical acts, such as throwing things, punching a wall, or slamming doors. In more extreme and rare cases, anger can lead to physical fights, such as hitting others.

Why do people with TBI have problems with irritability, anger, and aggression?

- Injury to parts of the brain that control how we feel and manage our emotions. TBI often causes injury to one or more of the many parts of the brain that control how we feel and manage our emotions. An example is the orbitofrontal region (pictured to the right). This front part of the brain helps us to monitor and evaluate our feelings, and to think rationally about situations. This helps keep our anger in check and stops us from being impulsive and aggressive. It helps us figure out appropriate ways to deal with our anger and the situation. People who have injured this part of their brain often have trouble controlling their anger and aggression.

- Changes in how the person thinks. After a TBI, changes such as slowed thinking, trouble focusing, poor memory, or difficulty solving problems can occur. These issues can be frustrating and may increase irritability and anger.

- Emotional struggles. Irritability is often a sign that a person is dealing with other emotional struggles, such as feeling sad, depressed, and/or anxious.

- Not fully recognizing emotions. People with TBI may find it hard to know when they are getting upset or irritated. As a result, feelings of anger can easily grow and get out of control.

- Adjusting to the injury. Many people with TBI have a hard time coping with changes after their injury. Limitations in activities and responsibilities (e.g., driving, managing bills, household chores) may make them feel irritable or angry.

- Misunderstanding others. TBI can affect a person’s ability to interpret other people’s actions and emotions. They may think that other people are angry or have bad intentions when they don’t. This can lead to anger.

- Feeling unwell. Pain, fatigue, and poor sleep are common after TBI. These can lead to irritability and aggression.

- Sensitivities to surroundings. People with TBI may be more sensitive to light and/or noise. This can lead to irritability.

RELATED FACTSHEETS

FACTSHEETS

FACTSHEETS

FACTSHEETS

What are the consequences of irritability, anger, and aggression after TBI?

Below are some common areas that can be impacted by these emotional and behavioral changes:

- Negative health effects. Anger may cause a faster heart rate and the person may be in a constant state of alert. In the long term, this can have negative physical health effects and mental health effects, such as heart disease and anxiety.

- Intimate relationships. It may be difficult for others to relate to a person who is easily irritated, angry, or aggressive. Unpredictable reactions may make partners feel as if they have to “walk on eggshells” around the person with TBI. This can lead to stress, conflict, and/or fear, and the quality of the relationship may suffer.

- Friendships. Friends of persons with TBI may have similar reactions as spouses or partners do. If not addressed, friendships are likely to dwindle and it may be harder to make new friends.

- Return to work. Trouble controlling emotions and behaviors can lead to friction or arguments with peers and employers. Irritability can make learning new skills and receiving critical feedback from others more difficult. Aggressive or defensive behaviors may lead to disciplinary action or job loss.

- Legal troubles. Due to the injury, a person with TBI may have difficulty controlling impulsive and inappropriate reactions when they are irritable or angry. Some acts may even be illegal (e.g. property damage, assault) and can result in fines, arrests, or even incarceration. Reasons for these actions after TBI can often be misunderstood. If someone with a TBI is accused of an illegal act, law enforcement and the legal system should consider recommending rehabilitation services that can treat the person’s needs, as opposed to criminal punishment.

How can health care providers help reduce irritability, anger, and aggression?

Find a licensed health care provider who is trained in treating emotional problems after TBI. Examples include psychologists, rehabilitation counselors, physiatrists (physicians who specialize in rehabilitation), social workers, occupational therapists, or speech pathologists. The following methods are often used by providers with good results.

- Psychotherapy or counseling. Healthcare providers, such as psychologists or licensed professional counselors, can help people with TBI learn to cope with anger and related emotions (e.g., posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression) in healthy ways. They may do this in different ways, such as helping people to notice their thoughts and feelings without judging them, helping them to evaluate how their thougts or feelings may be leading them to act in unhealthy ways, and/or assisting them to evaluate the accuracy of their thinking.

- Problem solving. Some health care providers can help people with TBI learn problem-solving skills, which is known to reduce anger and aggression.

- Early detection. Some health care providers can teach people with TBI how to spot early warning signs of irritability and anger so that they can try to lessen the chance that they will become aggressive. Meditation and mindfulness can help people notice how they feel and calm themselves.

- Social skill training. Some providers can help persons with TBI re-learn key social skills that are often impacted by the brain injury. This may help the person with the TBI to better understand others’ thoughts, intentions, and feelings (e.g., to see things from others’ perspective). This can prevent misunderstandings and reduce anger and aggression.

- Medications. Doctors can use medicines to treat irritability, anger, and aggression. However, no medicines have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for behavioral problems related to TBI. After TBI, people may be more sensitive to medicines. Talk to your doctor about what changes you notice in yourself with the medicine and side effects for all the prescription medications you are taking.

What can a person with TBI do to help reduce irritability, anger, and aggression?

- Rest. Try to get at least 7 hours of sleep every night. If you are having trouble sleeping, consult a physician or other health care provider.

- Move your body. Make sure to exercise, such as walking or doing yoga, every day.

- Relax. Practice relaxation exercises, like mindfulness, meditation, and/or deep breathing every day.

- Practice a healthy diet. Drink eight glasses of water every day, eat healthy foods, and don’t use recreational drugs or alcohol.

- Remember your medications. Make sure to take the medications your doctor has prescribed for you (see above).

How can caregivers help people with TBI reduce their irritability, anger, and aggression?

Caregivers often find their loved one’s irritability, anger, and aggression to be some of the most difficult changes to deal with after the injury. Here are some helpful hints for caregivers.

- Notice patterns. Be aware of things that cause irritability or anger. Being tired, overstimulated, or too hot may be triggers. Some topics, like being reminded of things that he or she has difficulty with, may be very upsetting for the person with TBI. Try to be sensitive about triggers such as these. It’s not your job to avoid every situation that may trigger these emotions, but noticing patterns can be helpful.

- Empathize and try to understand the problem. Do your best to understand where the person with TBI is coming from and what is causing your loved one to be upset. Realize that something you are doing or saying may be interpreted in a way that triggers their anger. Try to help resolve the situation that is upsetting the person.

- Manage your own expectations and emotions. Make sure your expectations of the person are realistic. Try to remain calm in response to anger and aggression. Suggest a break until everyone has calmed down. Go to another room or leave the house if needed. Come back later to talk calmly. Consider attending caregiver support groups for support, and/or make sure to get help and care from other family and friends.

- Agree on ground rules for communication. Everyone should agree to be respectful toward one another. For instance, speak calmly, without yelling or any other aggressive behavior.

- Focus on positive behavior. Pay attention to and reward positive behaviors, such as when the person calmly expresses his/her feelings. Try not to respond to negative behaviors, which can sometimes increase them.

- Try not to take things personally. Understand the injury to the brain often makes it harder for the person to manage anger and other emotions. Knowing that it is not personal or not the person’s fault may help you stay calm.

- Note any safety concerns. Your safety and the safety of other family members is important. If you have safety concerns about yourself or your loved one, talk to your doctor or another health professional. In some cases, you may need to consider living apart from the person with TBI.

Recommended Readings

- You Did That on Purpose! Misinterpretations and Anger after Brain Injury

- Anger and Frustration After Brain Injury (Brainline.org)

- MSKTC TBI resources at https://msktc.org/tbi on:

Authorship

Irritability, Anger, and Aggression After TBI was developed by Dawn Neumann, PhD, Shannon R. Miles, PhD, Angelle Sander, PhD, and Brian Greenwald, MD in collaboration with the Model Systems Knowledge Translation Center. Special thanks to Sagar Parikh, MD, for creating the picture of the brain used in this factsheet.

Source:The content in this factsheet is based on research and/or professional consensus. This content has been reviewed and approved by experts from the Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems (TBIMS) program, funded by the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR), as well as experts from the Polytrauma Rehabilitation Centers (PRCs), with funding from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

Disclaimer: This information is not meant to replace the advice of a medical professional. You should consult your health care provider regarding specific medical concerns or treatment. The contents of this factsheet were developed under grants from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90DP0082, 90DPTB0016, 90DRTB0002, and 90DPTB0014). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this factsheet do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the federal government.

Copyright © 2021 Model Systems Knowledge Translation Center (MSKTC). May be reproduced and distributed freely with appropriate attribution. Prior permission must be obtained for inclusion in fee-based materials.

[ARTICLE] Feasibility of a self-directed upper extremity training program to promote actual arm use for individuals living in the community with chronic stroke – Full Text

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Paretic Hand, REHABILITATION on January 28, 2024

Highlights

- •Distinct from clinic-based rehabilitation, self-directed rehabilitation approaches must address unique challenges related to decreased client motivation and adherence

- •Shared decision making and behavior change frameworks can support the implementation of UE self-directed rehabilitation

- •The Use My Arm-Remote program was feasible and safe to implement for individuals living in the community with chronic stroke

ABSTRACT

Objective

To determine the feasibility of a self-directed training protocol to promote actual arm use in everyday life. The secondary aim was to explore the initial efficacy on upper extremity (UE) outcome measures.

Design

Feasibility study using multiple methods.

Setting

Home and outpatient research lab.

Participants

15 adults (6 women, 9 men, mean age =53.08 years) with chronic stroke living in the community. There was wide range of UE functional levels, ranging from dependent stabilizer (limited function) to functional assist (high function).

Intervention

Use My Arm-Remote protocol. Phase 1 consisted of clinician training on motivational interviewing (MI). Phase 2 consisted of MI sessions with participants to determine participant generated goals, training activities, and training schedules. Phase 3 consisted of UE task-oriented training (60 minutes/day, 5 days/week, for 4 weeks). Participants received daily surveys through an app to monitor arm training behavior and weekly virtual check-ins with clinicians to problem-solve challenges and adjust treatment plans.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measures were feasibility domains after intervention, measured by quantitative study data and qualitative semi-structured interviews. Secondary outcomes included the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM), Motor Activity Log (MAL), Fugl-Meyer Assessment (FMA), and accelerometry-based duration of use metric measured at baseline, discharge, and 4-week follow-up.

Results

The UMA-R was feasible in the following domains: recruitment rate, retention rate, intervention acceptance, intervention delivery, intervention adherence, and safety. Improvements in UE outcomes were achieved at discharge and maintained at follow-up as measured by COPM-Performance subscale (F[1.42, 19.83]=17.72, p<0.001) and COPM-Satisfaction subscale (F[2, 28]=14.73, p<0.001), MAL (F[1.31, 18.30]=12.05, p<.01) and the FMA (F[2, 28]=16.62, p<0.001).

Conclusion

The UMA-R was feasible and safe to implement for individuals living in the community with chronic stroke. Participants demonstrated improvements in standardized UE outcomes to support initial efficacy of the UMA-R. Shared decision-making and behavior change frameworks can support the implementation of UE self-directed rehabilitation. Our results warrant the refinement and further testing of the UMA-R.

Graphical abstract

[…]

[WEB] Discover the C-Brace: The Revolution in Orthotics

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Gait Rehabilitation - Foot Drop, REHABILITATION, Video on January 27, 2024

The C-Brace stands as the pioneering mechatronic Stance and Swing Phase Control Orthosis (SSCO®) system in the world. It skillfully combines hydraulic control of both stance and swing phases with advanced microprocessor sensor technology. Unlike traditional paralysis orthoses, which only offer knee joint locking and releasing, the C-Brace delivers continuous support throughout the entire gait cycle, adjusting in real-time to various daily activities.

Key Highlights of the C-Brace:

- Unparalleled Innovation: As the only intuitive Knee-Ankle-Foot Orthosis (KAFO) of its kind, the C-Brace stands out from alternatives that require more effort and manual intervention for daily use.

- Adaptive and Responsive: The C-Brace uniquely learns and adapts to your patients’ movements, offering unmatched stability and confidence in their everyday activities.

- Hands-Free Mobility: With its groundbreaking technology, the C-Brace allows users complete hands-free mobility across various actions – be it walking, sitting, standing, or navigating stairs and ramps.

Empirical Evidence of Efficacy (2023 Study):

- Enhanced Balance: Users experienced a notable 20% improvement in balance with the C-Brace, compared to conventional KAFOs.

- Substantial Fall Reduction: A significant 73% decrease in falls was observed, markedly reducing users’ fear of falling.

- Quality of Life Improvements: Participants reported marked enhancements in 5 out of 9 quality of life areas, including a 50% increase in Physical Functioning, as per the global quality of life assessment.

- Reduced Dependence on Walking Aids: The study noted a considerable decrease in the need for walking aids during everyday activities.

For more comprehensive clinical data, download the C-Brace Evidence Essentials here.

Tailored for Individual Needs:

Each C-Brace is meticulously crafted to fit the unique anatomical requirements and specific conditions of the patient. This personalized approach ensures an optimal fit and function, involving several steps for evaluation and fitting for each potential user.

Identifying Suitable Candidates:

Our comprehensive list of indications assists in pinpointing the ideal candidates for the C-Brace. If you have a patient who might benefit from this innovative orthosis, please use the link below to request more information and arrange an in-person demo.

For Medical Professionals:

If you’re a healthcare professional seeking detailed information, please complete the form below and a dedicated Ottobock representative will contact you to provide personalized assistance.

Who is the C-Brace for?

Cognitive requirements

- The patient must be capable of ensuring the proper handling, care, and use of the orthosis (e.g. charging the battery, operating the user app, etc.)

Functional deficit

- Neuromuscular or orthopedic instability of the knee joint in the sagittal plane diagnosis (by the physician)

Has one or more of the following conditions:

- Quadricep weakness

- Charcot Marie Tooth Syndrome (CMT)

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Polio

- Spinal Cord Injury

- Hip/Knee/Ankle Injury

- Guillain-Barre Syndrome

- Stroke victim

- Deep vein thrombosis (DVT)

- Paraplegic

- Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP)

- Transverse/Partial Myelitis

- Neuro Lyme Disease

- Fibromyalgia

- Osteogenesis Imperfecta

- Ehlers Danlos Syndrome

Disclaimer: Not all people with one or more of these conditions will be a candidate for C-Brace but should still be considered.

Indications:

The C-Brace may be considered for patients with all neurologic conditions resulting in paresis or paralysis of the knee extensors, or orthopedic conditions in which the quadriceps fail to keep the knee extended during stance phase who do not present any of the contraindications. The leading indications are incomplete paraplegia with very minor or no spasticity, as well as post-polio syndrome, the condition following poliomyelitis.

Other factors to consider:

- The patient must be able to fully stabilize their torso.

- The muscle strength of their hip extensors and flexors must permit controlled swing-through of the affected leg.

- Compensatory hip movement is permissible.

- The patient must fulfill the physical and mental requirements for perceiving optical/acoustic signals and/or mechanical vibrations.

Contraindications:

- Inability to advance the limb through compensatory motion or grade 3 hip flexor

- Insufficient trunk stability

- Moderate to severe spasticity

- A flexion contraction of more than 10° in the knee and/or hip joint

- Genu varus/valgus of more than 10° that cannot be corrected

- Body weight > 275 lbs.

- Leg length discrepancy > 6 in.

Videos

C-Brace Playlist – Therapy Exercises

Life with the C-Brace

Hannah

Melvin

Wolfgang

C-Brace Gait Comparison Videos

David

Denise

Heike

Melvin

Rebecca

[Abstract + References] Effects of home-based exercise interventions on post-stroke depression: A systematic review and network meta-analysis

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Depression, Tele/Home Rehabilitation on January 25, 2024

Abstract

Background

Post-stroke depression (PSD) is a common and persistent mental disorder that negatively impacts stroke outcomes. Exercise-based interventions have been shown to be an effective non-pharmacological treatment for improving depression in patients with mild stroke, but no reviews have yet synthesized the effects of home-based exercise on PSD.

Objective

The purpose of this systematic review and network meta-analysis was synthesize the available evidence to compare the effectiveness of different types of home-based exercise programs on PSD and identify the optimal home-based exercise modality to inform clinical decision-making for the treatment of PSD.

Methods

PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Library, CINAHL, and PsycINFO were systematically searched from their inception dates to March 7, 2023. We searched for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of home-based exercise for PSD in adults aged 18 years and older. Only scores of depression retrieved directly post-treatment were included as the primary endpoint for the analysis. Version 2 of the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (RoB − 2) was used to assess the quality of included studies. We conducted traditional pairwise meta-analysis for direct comparisons using Review Manager 5.4.1, followed by network meta-analysis using Stata 15.1 for both the network evidence plot and analysis. Surface under the cumulative ranking curves (SUCRA) was used to estimate the intervention hierarchy. The protocol was registered with PROSPERO under registration number CRD42022363784.

Results

A total of 517 participants from nine RCTs were included. Based on the ranking probabilities, mind-body exercise was the most effective way in improving PSD (SUCRA: 90.4%, Hedges’ g: − 0.59, 95% confidence interval [CI]: − 1.16 to − 0.02), followed by flexibility/neuro-motor skills training (SUCRA: 42.9%, Hedges’ g: − 0.10, 95% CI: − 0.70 to 0.49), and aerobic exercise (SUCRA: 39.3%, Hedges’ g: − 0.07, 95% CI: − 0.81 to 0.67). We performed a subgroup analysis of mind-body exercise. In mind-body exercise interventions, Tai Chi was the most effective way to improve PSD (SUCRA: 99.4%, Hedges’ g: − 0.94, 95% CI: − 1.28 to − 0.61).

Conclusions

Our network meta-analysis provides evidence with very low certainty indicates potential benefits of home-based exercise for alleviating PSD, with mind-body exercises, notably Tai Chi, showing promise as an effective treatment. However, further rigorous studies are needed to solidify these findings. Specifically, multicenter RCTs comparing specific exercises to no intervention are crucial, assessing not only efficacy but also dose, reach, fidelity, and long-term effects for real-world optimization.

References (56)

- S. Chen et al.Effectiveness of a home-based exercise program among patients with lower limb spasticity post-stroke: A randomized controlled trialAsian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci)(2021)

- N.F. Chi et al.Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Home-Based Rehabilitation on Improving Physical Function Among Home-Dwelling Patients With a StrokeArch Phys Med Rehabil(2020)

- K. de Menezes et al.Home-Based Interventions may Increase Recruitment, Adherence, and Measurement of outcomes in Clinical Trials of Stroke RehabilitationJ Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis(2021)

- L.R. Nascimento et al.Home-based exercises are as effective as equivalent doses of centre-based exercises for improving walking speed and balance after stroke: a systematic reviewJ Physiother(2022)

- X. Zhou et al.Comparative efficacy and acceptability of antidepressants, psychotherapies, and their combination for acute treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysisLancet Psychiatry(2020)

- “National Clinical Guideline for Stroke for the UK and Ireland. London: Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party; 2023 May…

- Barnes, P. M., Powell-Griner, E., McFann, K. & Nahin, R. L. (2004), “Complementary and alternative medicine use among…

- A. Beserra et al.Can physical exercise modulate cortisol level in subjects with depression? A systematic review and meta-analysisTrends Psychiatry Psychother(2018)

- Brignardello-Petersen, R., Florez, I. D., Izcovich, A., Santesso, N., Hazlewood, G., Alhazanni, W., Yepes-Nunez, J. J.,…

- Cai, W., Mueller, C., Li, Y. J., Shen, W. D. & Stewart, R. (2019), “Post stroke depression and risk of stroke…

- P. Chaiyawat et al.Effectiveness of home rehabilitation for ischemic strokeNeurol Int(2009)

- W. Chan et al.Yoga and exercise for symptoms of depression and anxiety in people with poststroke disability: a randomized, controlled pilot trialAltern Ther Health Med(2012)

- Higgins, J., Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ & Welch, V. (2022), “Cochrane Handbook for Systematic…

- Das, J. & Rajanikant, G. K. (2018), “Post stroke depression : The sequelae of cerebral stroke”, NEUROSCIENCE AND…

- M. Egger et al.Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical testBMJ(1997)

- V.L. Feigin et al.Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019The Lancet Neurology(2021)

- Frank, D., Gruenbaum, B. F., Zlotnik, A., Semyonov, M., Frenkel, A. & Boyko, M. (2022), “Pathophysiology and Current…

- C.E. Garber et al.American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exerciseMed Sci Sports Exerc(2011)

- A. Gelineau et al.Compliance with Upper Limb Home-Based Exergaming Interventions for Stroke Patients: A Narrative ReviewJ Rehabil Med(2022)

- J. Guo et al.The advances of post-stroke depression: 2021 updateJ Neurol(2022)

- E. HarkinExploring Tai Chi as an early intervention to improve balance and reduce falls among stroke survivors-a feasibility studyInternational Journal of Stroke(2019)

- J.P. Higgins et al.Consistency and inconsistency in network meta-analysis: concepts and models for multi-arm studiesRes Synth Methods(2012)

- M.A. Immink et al.Randomized controlled trial of yoga for chronic poststroke hemiparesis: motor function, mental health, and quality of life outcomesTop Stroke Rehabil(2014)

- Israely, S., Leisman, G. & Carmeli, E. (2017), “Improvement in arm and hand function after a stroke with task-oriented…

- K.L. Lanctot et al.Canadian Stroke Best Practice Recommendations: Mood, Cognition and Fatigue following Stroke, 6th edition update 2019Int J Stroke(2020)

- B. Lane et al.The effectiveness of group and home-based exercise on psychological status in people with ankylosing spondylitis: A systematic review and meta-analysisMusculoskeletal Care(2022)

- Lapointe, T., Houle, J., Sia, Y. T., Payette, M. & Trudeau, F. (2023), “Addition of high-intensity interval training to…

- Li, C., Zhao, M., Sun, T., Guo, J., Wu, M., Li, Y., Luo, H., Wang, X. & Li, J. (2022), “Treatment effect of exercise…

There are more references available in the full text version of this article.

[ARTICLE] Rehabilitation via HOMe-Based gaming exercise for the Upper limb post Stroke (RHOMBUS): a qualitative analysis of participants’ experience – Full Text

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Paretic Hand, Tele/Home Rehabilitation, Video Games/Exergames on January 25, 2024

Abstract

Objective To report participants’ experiences of trial processes and use of the Neurofenix platform for home-based rehabilitation following stroke. The platform, consisting of the NeuroBall device and Neurofenix app, is a non-immersive virtual reality tool to facilitate upper limb rehabilitation following stroke. The platform has recently been evaluated and demonstrated to be safe and effective through a non-randomised feasibility trial (RHOMBUS).

Design Qualitative approach using semistructured interviews. Interviews were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim and analysed using the framework method.

Setting Participants’ homes, South-East England.

Participants Purposeful sample of 18 adults (≥18 years), minimum 12 weeks following stroke, not receiving upper limb rehabilitation prior to the RHOMBUS trial, scoring 9–25 on the Motricity Index (elbow and shoulder), with sufficient cognitive and communicative abilities to participate.

Results Five themes were developed which explored both trial processes and experiences of using the platform. Factors that influenced participant’s decision to take part in the trial, their perceptions of support provided during the trial and communication with the research team were found to be important contextual factors effecting participants’ overall experience. Specific themes around usability and comfort of the NeuroBall device, factors motivating persistence and perceived effectiveness of the intervention were highlighted as being central to the usability and acceptability of the platform.

Conclusion This study demonstrated the overall acceptability of the platform and identified areas for enhancement which have since been implemented by Neurofenix. The findings add to the developing literature on the interface between virtual reality systems and user experience.

Introduction

Despite advancements in prevention, treatment and rehabilitation, stroke remains a leading cause of disability worldwide1 including in the UK where an estimated 77% of first-ever stroke survivors present with upper limb weakness.2 Less than 20% of stroke survivors regain full function of the upper limb at 6 months.3

A combination of poor upper limb recovery and evidence that conventional rehabilitation results in insufficient upper limb training4–6 has resulted in an increasing interest in alternative training programmes. Novel approaches include virtual reality (VR) platforms to intensify upper limb training,7–9 while providing motivational feedback to encourage engagement and the required repetition to drive recovery.10 11 Studies have demonstrated VR devices can encourage higher numbers of repetitions, provide immediate feedback on performance and stimulate the visual, auditory and tactile senses to increase neuroplasticity, therefore contributing to improvements in motor function and performance of daily activities.12 13 Within qualitative work in the field a common theme that has emerged between studies is the beneficial effect VR has on motivation and engagement with upper limb rehabilitation.14 15 Initial evidence suggests such platforms are safe and effective at improving impairment, activity and participation, with the current Cochrane Review stating that VR may be beneficial for the upper limb when used as an adjunct to usual care; however, the evidence is currently considered to be of low quality.7 16–20 A recent meta-analysis, which compared VR interventions that included gaming components with those which just provided visual feedback, found that the inclusion of gaming components produced larger treatment gains.21

Despite encouraging outcomes, platforms used to date are often inaccessible to stroke survivors due to cost and the physical demands of the user interface.11 22–27 A recent systematic review of the acceptability of these platforms indicated several desirable features such as usability, small size, ease of set-up, sufficient support and engagement through variability, challenge and performance-based feedback.28