Posts Tagged TBI

[WEB] Understanding and Coping With Irritability, Anger, and Aggression After TBI – Factsheets

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Caregivers, TBI on January 28, 2024

What are irritability, anger, and aggression and how can you recognize them?

- Irritability is an emotional state in which a person has a short temper and is easily annoyed or angered. As a result, small things can lead to harsh reactions (for example, snapping at family or friends). This is most likely to happen if the person does not know how to manage their feelings or if the person is stressed. People may feel tense, uptight, touchy, or on edge when they are irritable.

- Anger is an emotion. It’s a strong feeling of annoyance or displeasure. Sometimes angry emotions can get intense and feel out of one’s control. Anger can lead to aggressive acts. When angry, people may feel tension in their forehead, jaw, shoulders, or fists. They may feel their heart beat faster and their bodies may feel hot.

- Aggression is a type of behavior. It is often an expression of anger. Actions can range from mildly aggressive to extremely aggressive. Aggression can be hurtful comments—what you say and how you say it. It may include insults, cursing, or yelling. On the more extreme and less common end, it can include acts of violence, such as throwing things or hitting someone or something. Aggression may include other threatening actions meant to cause fear or displeasure, such as following a driver on the highway to intimidate them or refusing to do something your loved one wants to do.

- As shown below, irritability, anger, and aggression are not the same, but they can overlap or occur together. However, each can also happen on their own. For instance, someone could feel angry but not act aggressively, or someone could get angry without being irritable. Tips for managing these emotions and behaviors are presented below.

What changes can be expected after a TBI?

Feeling irritable or angry from time to time is common for most people, but a TBI may cause changes that make these feelings more of a problem.

- Irritability and anger are more common in people with TBI than they are in people without TBI. Some research shows that up to three-fourths of people with TBI have irritability. In addition, up to 50% of people with TBI have problems with anger. A person who was not prone to irritability or anger before their TBI may now be easily irritated or angered after their TBI.

- Irritability and anger after TBI can be sudden and unpredictable. After a TBI, feelings of irritability and anger can occur suddenly and ramp up quickly. These feelings may be triggered more easily than before the TBI. They may also be hard to predict.

- Anger and aggression can lead to behaviors that are difficult to control after a TBI. A TBI can make it hard for a person to talk in a respectful way about things that make him/her angry or frustrated. The person may also find it hard to stop an aggressive response, such as shouting, saying mean things, or cursing. Sometimes, they may express anger through physical acts, such as throwing things, punching a wall, or slamming doors. In more extreme and rare cases, anger can lead to physical fights, such as hitting others.

Why do people with TBI have problems with irritability, anger, and aggression?

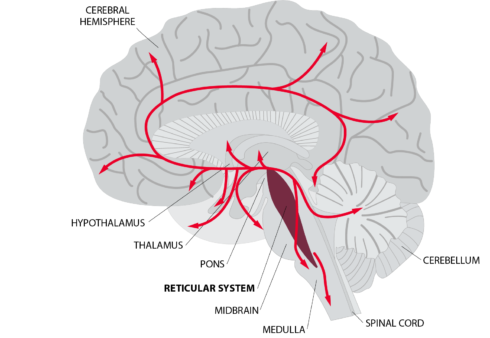

- Injury to parts of the brain that control how we feel and manage our emotions. TBI often causes injury to one or more of the many parts of the brain that control how we feel and manage our emotions. An example is the orbitofrontal region (pictured to the right). This front part of the brain helps us to monitor and evaluate our feelings, and to think rationally about situations. This helps keep our anger in check and stops us from being impulsive and aggressive. It helps us figure out appropriate ways to deal with our anger and the situation. People who have injured this part of their brain often have trouble controlling their anger and aggression.

- Changes in how the person thinks. After a TBI, changes such as slowed thinking, trouble focusing, poor memory, or difficulty solving problems can occur. These issues can be frustrating and may increase irritability and anger.

- Emotional struggles. Irritability is often a sign that a person is dealing with other emotional struggles, such as feeling sad, depressed, and/or anxious.

- Not fully recognizing emotions. People with TBI may find it hard to know when they are getting upset or irritated. As a result, feelings of anger can easily grow and get out of control.

- Adjusting to the injury. Many people with TBI have a hard time coping with changes after their injury. Limitations in activities and responsibilities (e.g., driving, managing bills, household chores) may make them feel irritable or angry.

- Misunderstanding others. TBI can affect a person’s ability to interpret other people’s actions and emotions. They may think that other people are angry or have bad intentions when they don’t. This can lead to anger.

- Feeling unwell. Pain, fatigue, and poor sleep are common after TBI. These can lead to irritability and aggression.

- Sensitivities to surroundings. People with TBI may be more sensitive to light and/or noise. This can lead to irritability.

RELATED FACTSHEETS

FACTSHEETS

FACTSHEETS

FACTSHEETS

What are the consequences of irritability, anger, and aggression after TBI?

Below are some common areas that can be impacted by these emotional and behavioral changes:

- Negative health effects. Anger may cause a faster heart rate and the person may be in a constant state of alert. In the long term, this can have negative physical health effects and mental health effects, such as heart disease and anxiety.

- Intimate relationships. It may be difficult for others to relate to a person who is easily irritated, angry, or aggressive. Unpredictable reactions may make partners feel as if they have to “walk on eggshells” around the person with TBI. This can lead to stress, conflict, and/or fear, and the quality of the relationship may suffer.

- Friendships. Friends of persons with TBI may have similar reactions as spouses or partners do. If not addressed, friendships are likely to dwindle and it may be harder to make new friends.

- Return to work. Trouble controlling emotions and behaviors can lead to friction or arguments with peers and employers. Irritability can make learning new skills and receiving critical feedback from others more difficult. Aggressive or defensive behaviors may lead to disciplinary action or job loss.

- Legal troubles. Due to the injury, a person with TBI may have difficulty controlling impulsive and inappropriate reactions when they are irritable or angry. Some acts may even be illegal (e.g. property damage, assault) and can result in fines, arrests, or even incarceration. Reasons for these actions after TBI can often be misunderstood. If someone with a TBI is accused of an illegal act, law enforcement and the legal system should consider recommending rehabilitation services that can treat the person’s needs, as opposed to criminal punishment.

How can health care providers help reduce irritability, anger, and aggression?

Find a licensed health care provider who is trained in treating emotional problems after TBI. Examples include psychologists, rehabilitation counselors, physiatrists (physicians who specialize in rehabilitation), social workers, occupational therapists, or speech pathologists. The following methods are often used by providers with good results.

- Psychotherapy or counseling. Healthcare providers, such as psychologists or licensed professional counselors, can help people with TBI learn to cope with anger and related emotions (e.g., posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression) in healthy ways. They may do this in different ways, such as helping people to notice their thoughts and feelings without judging them, helping them to evaluate how their thougts or feelings may be leading them to act in unhealthy ways, and/or assisting them to evaluate the accuracy of their thinking.

- Problem solving. Some health care providers can help people with TBI learn problem-solving skills, which is known to reduce anger and aggression.

- Early detection. Some health care providers can teach people with TBI how to spot early warning signs of irritability and anger so that they can try to lessen the chance that they will become aggressive. Meditation and mindfulness can help people notice how they feel and calm themselves.

- Social skill training. Some providers can help persons with TBI re-learn key social skills that are often impacted by the brain injury. This may help the person with the TBI to better understand others’ thoughts, intentions, and feelings (e.g., to see things from others’ perspective). This can prevent misunderstandings and reduce anger and aggression.

- Medications. Doctors can use medicines to treat irritability, anger, and aggression. However, no medicines have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for behavioral problems related to TBI. After TBI, people may be more sensitive to medicines. Talk to your doctor about what changes you notice in yourself with the medicine and side effects for all the prescription medications you are taking.

What can a person with TBI do to help reduce irritability, anger, and aggression?

- Rest. Try to get at least 7 hours of sleep every night. If you are having trouble sleeping, consult a physician or other health care provider.

- Move your body. Make sure to exercise, such as walking or doing yoga, every day.

- Relax. Practice relaxation exercises, like mindfulness, meditation, and/or deep breathing every day.

- Practice a healthy diet. Drink eight glasses of water every day, eat healthy foods, and don’t use recreational drugs or alcohol.

- Remember your medications. Make sure to take the medications your doctor has prescribed for you (see above).

How can caregivers help people with TBI reduce their irritability, anger, and aggression?

Caregivers often find their loved one’s irritability, anger, and aggression to be some of the most difficult changes to deal with after the injury. Here are some helpful hints for caregivers.

- Notice patterns. Be aware of things that cause irritability or anger. Being tired, overstimulated, or too hot may be triggers. Some topics, like being reminded of things that he or she has difficulty with, may be very upsetting for the person with TBI. Try to be sensitive about triggers such as these. It’s not your job to avoid every situation that may trigger these emotions, but noticing patterns can be helpful.

- Empathize and try to understand the problem. Do your best to understand where the person with TBI is coming from and what is causing your loved one to be upset. Realize that something you are doing or saying may be interpreted in a way that triggers their anger. Try to help resolve the situation that is upsetting the person.

- Manage your own expectations and emotions. Make sure your expectations of the person are realistic. Try to remain calm in response to anger and aggression. Suggest a break until everyone has calmed down. Go to another room or leave the house if needed. Come back later to talk calmly. Consider attending caregiver support groups for support, and/or make sure to get help and care from other family and friends.

- Agree on ground rules for communication. Everyone should agree to be respectful toward one another. For instance, speak calmly, without yelling or any other aggressive behavior.

- Focus on positive behavior. Pay attention to and reward positive behaviors, such as when the person calmly expresses his/her feelings. Try not to respond to negative behaviors, which can sometimes increase them.

- Try not to take things personally. Understand the injury to the brain often makes it harder for the person to manage anger and other emotions. Knowing that it is not personal or not the person’s fault may help you stay calm.

- Note any safety concerns. Your safety and the safety of other family members is important. If you have safety concerns about yourself or your loved one, talk to your doctor or another health professional. In some cases, you may need to consider living apart from the person with TBI.

Recommended Readings

- You Did That on Purpose! Misinterpretations and Anger after Brain Injury

- Anger and Frustration After Brain Injury (Brainline.org)

- MSKTC TBI resources at https://msktc.org/tbi on:

Authorship

Irritability, Anger, and Aggression After TBI was developed by Dawn Neumann, PhD, Shannon R. Miles, PhD, Angelle Sander, PhD, and Brian Greenwald, MD in collaboration with the Model Systems Knowledge Translation Center. Special thanks to Sagar Parikh, MD, for creating the picture of the brain used in this factsheet.

Source:The content in this factsheet is based on research and/or professional consensus. This content has been reviewed and approved by experts from the Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems (TBIMS) program, funded by the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR), as well as experts from the Polytrauma Rehabilitation Centers (PRCs), with funding from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

Disclaimer: This information is not meant to replace the advice of a medical professional. You should consult your health care provider regarding specific medical concerns or treatment. The contents of this factsheet were developed under grants from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90DP0082, 90DPTB0016, 90DRTB0002, and 90DPTB0014). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this factsheet do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the federal government.

Copyright © 2021 Model Systems Knowledge Translation Center (MSKTC). May be reproduced and distributed freely with appropriate attribution. Prior permission must be obtained for inclusion in fee-based materials.

[WEB] Is TBI a Chronic Condition?

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in TBI on January 21, 2024

People with traumatic brain injury (TBI) may continue to improve or decline years after their injury, making it a more chronic illness, according to a study published in Neurology, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology.

“Our results dispute the notion that TBI is a one-time event with a stagnant outcome after a short period of recovery,” says study author Benjamin L. Brett, PhD, of the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee. “Rather, people with TBI continue to show improvement and decline across a range of areas including their ability to function and their thinking skills.”

The study involved people at 18 level 1 trauma center hospitals with an average age of 41. A total of 917 people had mild TBI and 193 people had moderate to severe TBI. They were matched to 154 people with orthopedic injuries but no head injuries. Participants were followed for up to seven years.

Participants took three tests on thinking, memory, mental health, and ability to function with daily activities annually from two to seven years post-injury. They also completed an interview on their abilities and symptoms, including headache, fatigue, and sleep disturbances.

When researchers looked at all test scores combined, 21% of people with mild TBI experienced decline, compared to 26% of people with moderate to severe TBI and 15% of people with orthopedic injuries with no head injury.

Among the three tests, researchers saw the most decline over the years in the ability to function with daily activities. On average, over the course of 2 to 7 years post-injury, a total of 29% of those with mild TBI declined in their abilities and 23% of those with moderate to severe TBI.

Yet some people showed improvement in the same area, with 22% of those with mild TBI improving over time and 36% of those with moderate to severe TBI.

“These findings point out the need to recognize TBI as a chronic condition in order to establish adequate care that supports the evolving needs of people with this condition,” Brett says. “This type of care should place a greater emphasis on helping people who have shown improvement continue to improve and implementing greater levels of support for those who have shown decline.”

A limitation of the study was that all participants were seen at a level 1 trauma center hospital within 24 hours of their injury, so the findings may not apply to other populations.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institute on Aging, the National Football League Scientific Advisory Board and the U.S. Department of Defense.

[WEB] New Data on Traumatic Brain Injury Show It’s Chronic, Evolving

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in TBI on January 20, 2024

New longitudinal data from the TRACK TBI investigators show that recovery from traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a dynamic process that continues to evolve well beyond the initial 12 months after injury.

The data show that patients with TBI may continue to improve or decline during a period of up to 7 years after injury, making it more of a chronic condition, the investigators report.

“Our results dispute the notion that TBI is a discrete, isolated medical event with a finite, static functional outcome following a relatively short period of upward recovery (typically up to 1 year),” Benjamin Brett, PhD, assistant professor, Departments of Neurosurgery and Neurology, Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, told Medscape Medical News.

“Rather, individuals continue to exhibit improvement and decline across a range of domains, including psychiatric, cognitive, and functional outcomes, even 2 to 7 years after their injury,” Brett said.

“Ultimately, our findings support conceptualizing TBI as a chronic condition for many patients, which requires routine follow-up, medical monitoring, responsive care, and support, adapting to their evolving needs many years following injury,” he said.

Results of the TRACK TBI LONG (Transforming Research and Clinical Knowledge in TBI Longitudinal study) were published online June 21 in Neurology.

Chronic and Evolving

The results are based on 1264 adults (mean age at injury, 41 years) from the initial TRACK TBI study, including 917 with mild TBI (mTBI) and 193 with moderate/severe TBI (msTBI), who were matched to 154 control patients who had experienced orthopedic trauma without evidence of head injury.

The participants were followed annually for up to 7 years after injury using the Glasgow Outcome Scale–Extended (GOSE), Brief Symptom Inventory–18 (BSI), and the Brief Test of Adult Cognition by Telephone (BTACT), as well as a self-reported perception of function. The researchers calculated rates of change (classified as stable, improved, or declined) for individual outcomes at each long-term follow-up.

In general, “stable” was the most frequent change outcome for the individual measures from post-injury baseline assessment to 7 years post injury.

However, a substantial proportion of patients with TBI (regardless of severity) experienced changes in psychiatric status, cognition, and functional outcomes over the years.

When the GOSE, BSI, and BTACT were considered collectively, rates of decline were 21% for mTBI, 26% for msTBI, and 15% for OTC.

The highest rates of decline were in functional outcomes (GOSE scores). On average, over the course of 2 to 7 years post injury, 29% of patients with mTBI and 23% of those with msTBI experienced a decline in the ability to function with daily activities.

A pattern of improvement on the GOSE was noted in 36% of patients with msTBI and 22% patients with mTBI.

Notably, said Brett, patients who experienced greater difficulties near the time of injury showed improvement for a period of 2 to 7 years post injury. Patient factors, such as older age at the time of the injury, were associated with greater risk of long-term decline.

“Our findings highlight the need to embrace conceptualization of TBI as a chronic condition in order to establish systems of care that provide continued follow-up with treatment and supports that adapt to evolving patient needs, regardless of the directions of change,” Brett told Medscape Medical News.

Important and Novel Work

In a linked editorial, Robynne Braun, MD, PhD, with the Department of Neurology, University of Maryland, Baltimore, notes that there have been “few prospective studies examining post-injury outcomes on this longer timescale, especially in mild TBI, making this an important and novel body of work.”

The study “effectively demonstrates that changes in function across multiple domains continue to occur well-beyond the conventionally tracked 6–12-month period of injury recovery,” Braun writes.

The observation that over the 7-year follow-up, a substantial proportion of patients with mTBI and msTBI exhibited a pattern of decline on the GOSE suggests that they “may have needed more ongoing medical monitoring, rehabilitation or supportive services to prevent worsening,” Braun adds.

At the same time, the improvement pattern on the GOSE suggests “opportunities for recovery that further rehabilitative or medical services might have enhanced.”

The study was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Institute on Aging, the National Football League Scientific Advisory Board, and the US Department of Defense. Brett and Braun have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Neurology. Published online June 21, 2023. Abstract, Editorial

[WEB] Changes in Emotion After Traumatic Brain Injury – Factsheets

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in TBI on January 16, 2024

What causes emotional changes after TBI?

How to address emotional concerns after TBI

Family members can help by changing the way they react to emotional distress after TBI:

Peer support and other resources

The way people experience or express emotions may change after a traumatic brain injury (TBI). While this can be distressing for family members and friends, many strategies can help manage these emotional concerns after TBI.

Anxiety

Anxiety is common in the general population and in people with moderate to severe TBI. Anxiety may look different from person to person, but most people with anxiety have intense fear and worry. Some people also have physical signs of anxiety. For example, they may have a racing heart, rapid breathing, sweating, shaking, or the sensation of butterflies in their stomach. They may feel anxious, stressed, or overwhelmed without knowing why. This stress can make recovery after a TBI even more difficult. People with TBI may have anxiety in situations that did not bother them in the past. They may feel anxious being in a crowd, when they are being rushed, or when adjusting to sudden changes in plans. They may feel overwhelmed in situations that require a lot of attention, fast thinking, or processing a lot of information at the same time.

Depression

People with depression may feel sad, irritable, or worthless. They may feel tired much of the time and may experience changes in sleep or appetite or difficulty concentrating. Sometimes, people may even have thoughts of death, hurting themselves, or taking their own life. People with these feelings often withdraw from others and lose interest in or feel less pleasure from activities they used to enjoy. Many signs of depression, such as fatigue and frustration, are also signs of TBI. However, someone with a TBI may experience these symptoms but not be depressed. Sadness, and grief are common after brain injury. Some people feel depressed right after TBI, but these feelings may also appear during the later stages of recovery. Symptoms of anxiety may appear before depression. If these feelings become overwhelming or interfere with recovery, the person with TBI may be experiencing depression.

What causes emotional changes after TBI?

- Emotional changes can occur if the TBI affects areas of the brain that control emotions. Changes to these brain regions and to the chemicals that help the brain work can affect how the person with TBI experiences or expresses emotion.

- People with TBI may have a hard time coping with their injury. They may need to adjust to a loss of independence, or to changes to their role in their family and in society. These changes can lead to frustration and dissatisfaction with their life.

- People with TBI may also have changes in their thinking abilities, such as memory, attention, speed of thinking, and reasoning. These changes can cause them to feel overwhelmed if they can’t remember things or keep up with what others are doing or saying. They may respond emotionally, with sadness, worry, or anger.

- Use of alcohol or other drugs can lead to emotional changes, and emotional distress may also lead to alcohol and drug use.

- People who had problems with depression or anxiety before the TBI may find that these problems are worse after the TBI. They may feel isolated, depressed, or misunderstood which can also affect emotions.

How to address emotional concerns after TBI

- Remember that emotional distress is not a sign of weakness and it is no one’s fault. A person can’t get over their distress by wishing it away or “toughening up.”

- Medicine and counseling or psychotherapy can help with emotional distress after TBI. Sometimes, a combination of both works best.

- If you choose to take medicine, you should work closely with the doctor or provider who prescribed the medication. Be sure to attend all follow-up visits about your medicine.

- If you choose counseling or psychotherapy, let your therapist know about your TBI. Ask them to help you write important concepts down so that you can review them at home. Tell your therapist if you need to have something repeated in order to understand it better.

- Stress and stressful situations can trigger emotional distress. People with TBI can take steps to reduce stress. For example, they can use relaxation techniques such as deep breathing or muscle relaxation, schedule breaks, and practice mindfulness activities.

- A daily schedule of structured activities and exercise can help reduce distress. Activities may include exercise, puzzles, or games.

- It is best to get treatment early to avoid needless suffering. Do not wait.

- If you (or your family member) have thoughts of suicide, get help. You can call a local crisis line, 911, or the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255), or go to your local emergency room.

Family members can help by changing the way they react to emotional distress after TBI:

- Remember that anxiety, depression, irritability, and other changes in emotion after TBI may be due to brain injury. Try not to take it personally. Also remember that changes in emotion are no one’s fault and try not to blame the person with TBI.

- Stay calm and try not to react in an emotional way yourself or to argue with the person with TBI. If you are angry or hurt, take a break before you talk to them.

- When they are acting out in anger, do not give in to their demands to try to calm them down. This can actually have the opposite effect of rewarding them for expressing their emotions in a non-helpful way. Resist the urge to give in to unreasonable demands. Instead, explain that you will talk to them when they are calm. Walk away and take a break until they are calmer.

- Provide feedback in a gentle and supportive way after the person is calm.

- Give the person with TBI opportunities to take a break to process their emotions. Encourage them to use deep breathing or listen to music to relax. Offer a quiet area, away from the stressor, to calm down and regain control. Then, redirect their attention to a different topic or activity.

- Give the person with TBI time to have structured independence and more control over his or her life.

- Tell them you recognize their emotions and want to understand their feelings and give the person with TBI a chance to talk about their feelings. People with TBI often have a hard time naming their emotions and might find it hard to recognize emotions in others. This means that they may not realize that they seem angry or that they are making others uncomfortable. You can help them identify their emotions and tell them how you feel.

- Seek out support. The family may benefit from social and professional support. Counseling can help relieve the family’s worry and help them to cope better each day.

Peer support and other resources

Remember, not all help comes from professionals! You and your family may benefit from the following:

- Support groups: Some support groups are for the person with TBI, while others are for family members, and some are open to everyone affected by TBI. Information about support groups may be found through TBI organizations, rehabilitation facilities, and social media, among other places.

- Peer mentoring: A peer is a person who is currently living with a TBI. A peer can offer support and advice to others who are new to TBI and dealing with similar problems.

- Brain Injury Association (http://www.biausa.org): Reach out to your local chapter for resources, including training and resources for caregivers and family members.

- Find someone to talk to. Reach out to a friend, family member, member of the clergy, or someone else who is a good listener.

Recommended reading

- Senelick, R. C. (2013). Living with brain injury: A guide for patients and families (3rd ed.). Healthsouth Press.

- Brain Injury Association of New York State. (2004). Making life work after head injury: A family guide for life at home. https://bianys.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Making_Life_Work-after-TBI.pdf

- Cassidy, J. W. (2009). Mindstorms: The complete guide for families living with traumatic brain injury. De Capo Lifelong Books.

- Fann, J., & Hart, T. in collaboration with the Model Systems Knowledge Translation Center (2010) Depression after Traumatic Brain Injury . https://msktc.org/sites/default/files/lib/docs/Factsheets/TBI_Depression_and_TBI.pdf

- Neumann, D., Miles, S. R., Sander, A., & Greenwald, B. in collaboration with the Model Systems Knowledge Translation Center (2021). Irritability, Anger, and Aggression After TBI. https://msktc.org/sites/default/files/MSKTC-IrrAftTBI-Factsheet-508.pdf

[Abstract + References] Fatigue and traumatic brain injury – Literature review

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Fatigue, TBI on December 19, 2023

Abstract

Fatigue is frequent and disabling in patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI). Its mechanisms are complex and multifactorial. We performed a literature review of reports of the condition using the following key words: brain injury, depression, neuroendocrine dysfunction, and treatment. Five scales have been used to evaluate fatigue in TBI patients: the Fatigue Severity Scale, the visual analog scale (VAS) for fatigue, the Fatigue Impact Scale, the Barrow Neurological Institute (BNI) Fatigue Scale and the Cause of Fatigue (COF) Questionnaire. The BNI Fatigue Scale and the COF Questionnaire have been designed specifically for brain-injured patients. Fatigue is present in 43–73% of patients and is one of the first symptoms for 7% of them. Fatigue does not seem to be significantly related to injury severity not to time since injury. It can be related to mental effort necessary to overcome attention deficit and slowed processing (“coping hypothesis”). It can also be related to sleeping disorders and depression, although the relation between fatigue and depression are debated. Finally, fatigue can also be related to infraclinical pituitary insufficiency (growth hormone insufficiency, hypocorticism). To date, no published study of treatment of fatigue after TBI exists.

Introduction

Fatigue is common in patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI). According to recent studies, it is one of the most disabling symptoms, whatever the severity of injury [12], [28], [36]. Fatigue is a complex and subjective phenomenon. Its origins are multifactorial. It is an intimate, universal and extremely frequent experience that cannot be objectively measured. It appears in many different conditions: infection, toxic infection, cancer, inflammation, endocrine and metabolic abnormalities, sleep disturbances, depression, and neurological conditions.

Although many studies have reported this complaint, few have investigated the mechanisms and implications of fatigue. However, fatigue after TBI is constraining in daily life. It also interferes with the rehabilitation process and is a burden on return to work.

We performed a systematic bibliographic search of the MEDLINE database, using the following keywords: fatigue, brain injury, depression, neuroendocrine dysfunction, and treatment.

Section snippets

TBI

We consider TBI to be any brain damage, even trifling, related to an impact on the brain. In France, about 15,000–20,000 individuals per year are victims of TBI, including 5–10% with severe TBI, which could lead to disability. The prevalence is greater in men (sex ratio 2:1) and in the age bracket 12–25. Road traffic accidents represent the main cause of TBI (60–70%). Brain lesions after TBI are related to different mechanisms (direct or indirect head impact on acceleration and/or

Definitions

Fatigue is “the conscious decreased ability for a physical and/or mental activity due to an imbalance in availability, utilization or the retrieval of the physiological or psychological resources required to perform the activity” [1]. “Normal” fatigue is “a feeling of weariness related to the effort, to the excess of physical or intellectual exertion.” Such fatigue is a subjective phenomenon, which can be expressed as a lack of energy or motivation, weakness, fatigability, sleepiness,

Incidence of fatigue after TBI

Fatigue is a common and frequently disabling symptom after TBI. It is reported by 45–73% of patients [26], [33] and remains in 73% of patients after 5 years [26]. Fatigue represents the most disabling symptom for 7% of patients and the first one for 43% of them [20]. A significant positive correlation has been found between the FSS, the FIS and the 13 “fatigue” items of the VAS-F, as well as a significant negative correlation between the five “energy” items of the VAS-F and the other scales [20]

Sleep disorders

Sleep disorders are frequent after TBI (50–73%) [7], [10] and are a cause of fatigue, yet some tired patients do not have any sleep disorder and all the patients with sleep disorders do not have fatigue: Clinchot et al. [9] found that 50% of TBI patients had sleep disorders, 63% were tired, and among the 50% with sleep disorders, 80% complained of fatigue.

Depression

Research into the relation between fatigue and depression is lacking. The prevalence of depression after TBI is variable among studies

Treatment

Treatment of post-TBI fatigue includes pharmacology, rehabilitation and readaptation. Nowadays, there is no known specific treatment for fatigue. DeMarchi et al. [11] reviewed treatments used for awakening stimulation (psychostimulants, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, etc.) and showed no evidence for the efficacy of these treatments.

Conclusion

Like depression, fatigue is a limitation to the rehabilitation process in TBI. Van Zomeren’s coping hypothesis remains one of the most plausible explanations of post-TBI fatigue. Nevertheless, depression, sleep disorders and endocrine dysfunction are other causative factors that should be taken into consideration.

References (38)

- P. Azouvi et al.Divided attention and mental effort after severe traumatic brain injuryNeuropsychologia(2004)

- R.J. Castriotta et al.Sleep disorders associated with traumatic brain injuryArch. Phys. Med. Rehabil.(2001)

- J.L. Ingles et al.Fatigue after strokeArch. Phys. Med. Rehabil.(1999)

- K.A. Lee et al.Validity and reliability of a scale to assess fatiguePsychiatry Res.(1991)

- J.M. Mazaux et al.Long-term neuropsychological outcome and loss of social autonomy after traumatic brain injuryArch. Phys. Med. Rehabil.(1997)

- R.T. Seel et al.Depression after traumatic brain injury: a National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research Model Systems multicenter investigationArch. Phys. Med. Rehabil.(2003)

- L.S. Aaronson et al.Defining and measuring fatigueImage J. Nurs. Sch.(1999)

- P. Azouvi et al.Working memory and supervisory control after severe closed head injury. A study of dual task performance and random generationJ. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol.(1996)

- A. BelmontMémoire du DEA national de Neuropsychologie(2004)

- S.R. Borgaro et al.Fatigue after brain injury: initial reliability study of the BNI Fatigue ScaleBrain Inj.(2004)

View more references

[WEB] Fatigue After Brain Injury

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Fatigue on December 14, 2023

By Katherine Dumsa, OTR/L, CBIS and Angela Spears, MA, CCC-SLP, DPNS, CBIS, Rainbow Rehabilitation Centers

Fatigue is a part of life that is experienced by everyone. Whether it is from a busy day at work, a demanding workout, or after paying attention to a long lecture, the term “I’m tired” is exceedingly common.

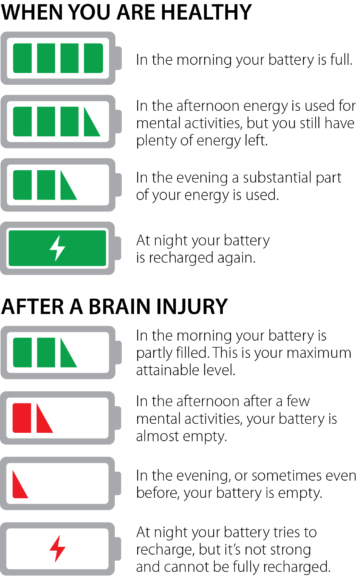

Fatigue and Traumatic Brain Injuries

For individuals with brain injuries, fatigue (sometimes referred to as cognitive fatigue, mental fatigue, or neurofatigue), is one of the most common and debilitating symptoms experienced during the recovery process. It can become a significant barrier to one’s ability to participate in the activities they want and need to do in daily life. It is reported that as many as 98% of people who have experienced a traumatic brain injury have some form of fatigue. Many report that fatigue is their most challenging symptom after brain injury. Reasons for the fatigue are not well understood but may include endocrine abnormalities, the need for the brain to work harder to compensate for brain injury deficits (in other words, inefficiency), or changes to brain structures.

Assessment Tools to Determine Fatigue Levels

Fatigue can be difficult to identify because it is not always reported by the patient or obvious to others. Clinicians use various self-report assessment tools to gain further information on a patient’s fatigue levels and the impact it has on their overall daily functioning. Two of the scales specifically designed for individual patients with brain injuries include the Barrow Neurological Institute Fatigue Scale (BNI) and the Cause of Fatigue Questionnaire (COF). Clinicians must also evaluate physical and mental changes, which can lead to depression and other psychiatric conditions following brain injury. The changes can commonly present as overwhelming fatigue.

Symptoms

Generally, those who have sustained brain injuries have described fatigue as a sense of mental or physical tiredness, exhaustion, lack of energy, and/or low vitality. Physical observations of fatigue include yawning, an appearance of confusion or “brain fog,” or easily losing attention and concentration. In more severe cases, it may present as forgetfulness, irritability, slurred speech, or dizziness. Emotions can become raw at this level of fatigue, affecting mood, motivation, and interaction with one’s social network. To manage fatigue effectively, individuals must learn to identify the symptoms of fatigue and how to modify activities that may trigger fatigue. Managing fatigue effectively will help decrease stress levels and improve overall performance for both work and home activities. Some fatigue-inducing activities include:

- Working at a computer

- Watching television excessively

- Having a stimulating sensory environment

- Concentrating on paperwork

- Reading for long periods of time

- Physically demanding tasks

- Cognitively demanding tasks

- Emotionally draining tasks

Symptoms of fatigue can include:

- Physical symptoms: a pale or greyish pallor, glazed eyes, headaches, tension in muscles, shortness of breath, slower movement and speech, decreased coordination, or difficulty staying awake:

- Cognitive symptoms: increased forgetfulness, distractibility, decreased ability to follow directions, making an increased number of mistakes, decreased awareness of surroundings, or increased response time or lack of response.

- Social/Emotional symptoms: decreased ability to communicate effectively, decreased ability to engage in social activities, irritability, restlessness, emotional lability, increased negative thoughts, withdrawal, short answers, dull tone of voice, lack of motivation and interest, or difficulty engaging in activities of daily living.

Fatigue Is Not Laziness

In today’s multi-media society, we take in, absorb, and process large amounts of information every day. It can be difficult for family members or peers to understand the limitations caused by fatigue following a brain injury. Unfortunately, it can be mistaken for laziness or an unwillingness to participate in therapies and daily activities. It is important to understand that lacking the mental energy needed to complete tasks does not equate to lacking the desire to complete those tasks. Many individuals struggling with fatigue have motivation but lack the energy to keep up with daily demands.

Coping Strategies Used to Ease Symptoms

When managing fatigue, it is important to identify and treat physical factors that may be contributing to the fatigue. Recognizing early signs of fatigue and working with the patient so they understand how to respond to these is beneficial. By learning to recognize these triggers, one can learn coping strategies to successfully meet daily demands, ultimately increasing quality of life. These strategies include:

- Having a healthy sleep routine – This can be done by setting a sleep schedule of when to go to bed and when to wake, regardless of the day of the week. Establishing a strict routine using an alarm clock allows the brain proper rest. When rest is needed, aim for a “power nap” of 30 minutes maximum to avoid feeling over tired for the remainder of the day. Lack of sleep has a negative effect on our cognition, mood, energy levels, and appetite. The American Academy of Neurology reports that as many as 40% to 65% of people with mild traumatic brain injury complain of insomnia, so maintaining a sleep hygiene program is essential to recovery and to managing fatigue.

- Practicing energy conservation – Pacing yourself each day, or prioritizing daily tasks to avoid becoming over-tired, can help with balancing out a busy schedule. Complete tasks that require the most mental effort earlier in the day with planned rest breaks in the afternoon or evening.

- Organizing daily activities – Utilize a checklist or planner to set a to-do list. Break up complex projects into manageable tasks. When completing these tasks, minimize environmental stimulation as much as possible.

- Improving health and wellness – Increased overall health and wellness has been described as “energizing,” and research suggests that it can improve mood. Aim to exercise three to five times per week for a minimum of 30 minutes per session. Maintain a well-balanced diet rich in protein, fiber, and carbohydrates to help the brain and body stay fully energized.

- Keeping a fatigue diary – This kind of diary can assist in monitoring changes and energy levels before and after daily activities. This tracking of fatigue can be used with your treatment team to help mitigate what may be increasing neurofatigue. Assessment and treatment of fatigue continues to be a challenge for clinicians and researchers. While there is no cure for fatigue, there are many ways to manage and overcome the symptom. Awareness and an open mind towards coping strategies will lessen the negative effects of fatigue and allow for meaningful participation in life.

References

- Keough, A. 2016. Strategies to manage neuro-fatigue.

- Cantor, J.H., Ashman, T., Gordon, W., Ginsberg, A., Engmann, C., Egan, M., Spielman, L., Dijkers, M., & Flanagan, S. (2008). Fatigue after traumatic brain injury and its impact on participation and quality of life. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 23(1), 41-51.

- Jang, S., & Kwon, H. (2016). Injury of the ascending reticular activating system in patients with fatigue and hypersomnia following mild traumatic brain injury. Medicine. 95(6). e2628.

- Belmont, A., Agar, N., Hugeron, B. Gallais, C. & Azouvi, P., Fatigue and traumatic brain injury. Annales de Réadaptation et de Médecine Physique. 49(6). 370-374.

- Johnson, G. (2000). Traumatic brain injury survival guide. Traverse City, MI.

- Heins, J., Sevat, R., Werkhoven, C. (n.d.) Neurofatigue. Brain Injury Explanation.

This article first appeared in the Summer 2018 issue of Rainbow Visions Magazine available at www.rainbowrehab.com.

This article originally appeared in Volume 15, Issue 2 of THE Challenge! published in 2021.

[WEB] How Does Sleep Affect Neurological Disorders?

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in REHABILITATION on October 16, 2023

[FACTSHEET] MSKTC Updates TBI Factsheet Booklet in English and Spanish

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in TBI on August 1, 2023

[Abstract] Treatment of sleep disturbance following stroke and traumatic brain injury: a systematic review of conservative interventions

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in TBI on July 30, 2023

Abstract

Purpose: Sleep disorders are common following stroke and traumatic brain injury. We present a systematic review of the literature investigating conservative interventions to improve sleep in these populations.

Materials and methods: The PRISMA statement was used. Embase, PubMed, and the Cochrane library were searched for all experimental studies published prior to 28th March 2020 that assessed conservative interventions to improve the sleep or sleep disorders of adults with a history of stroke or traumatic brain injury (TBI). Two authors reviewed publications of interest and risk of bias assessments were performed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool or the Methodological Index for Non-Randomised Studies instrument.

Results: Twenty-three publications were included in this systematic review. Meta-analyses were not performed due to study heterogeneity. Psychotherapy-based approaches might be useful for sleep disturbance after TBI and acupuncture may help improve insomnia or sleep disturbance following stroke or TBI, respectively. The evidence was less clear for morning bright light therapy and exercise. Limitations included a single author performing primary searches, only English publications, the reporting of secondary outcome measures, and sleep disorder diagnoses.

Conclusions: Some conservative interventions might be useful for improving sleep disturbance or disorders in these populations, but further research is required.IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATIONSleep disturbance is common following stroke and traumatic brain injury, with insomnia and obstructive sleep apnoea being the most frequently diagnosed sleep disorders.Psychotherapy-based approaches might be useful for sleep disturbance after TBI and acupuncture may help improve insomnia or sleep disturbance following stroke or TBI, respectively.Morning bright light therapy appeared to be more beneficial for fatigue rather than sleep disturbance after TBI, and the evidence for exercise was less clear.

Similar articles

- Sleep disturbance and recovery during rehabilitation after traumatic brain injury: a systematic review.Lowe A, Neligan A, Greenwood R.Disabil Rehabil. 2020 Apr;42(8):1041-1054. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2018.1516819. Epub 2019 Feb 1.PMID: 30707632

- Treating sleep disorders following traumatic brain injury in adults: Time for renewed effort?Stewart K, Shakarishvili N, Michalak A, Maschauer EL, Jenkins N, Riha RL.Sleep Med Rev. 2022 Jun;63:101631. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2022.101631. Epub 2022 Apr 14.PMID: 35623210 Review.

- Does cognitive-behavioural therapy improve sleep outcomes in individuals with traumatic brain injury: a scoping review.Ludwig R, Vaduvathiriyan P, Siengsukon C.Brain Inj. 2020 Oct 14;34(12):1569-1578. doi: 10.1080/02699052.2020.1831070. Epub 2020 Oct 28.PMID: 33112696 Review.

- Sleep after TBI: How the TBI Model Systems have advanced the field.Bell KR, Bushnik T, Dams-O’Connor K, Goldin Y, Hoffman JM, Lequerica AH, Nakase-Richardson R, Zumsteg JM.NeuroRehabilitation. 2018;43(3):287-296. doi: 10.3233/NRE-182538.PMID: 30347631 Review.

- Non-pharmacological treatment for insomnia following acquired brain injury: A systematic review.Ford ME, Groet E, Daams JG, Geurtsen GJ, Van Bennekom CAM, Van Someren EJW.Sleep Med Rev. 2020 Apr;50:101255. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2019.101255. Epub 2019 Dec 19.PMID: 31927422

[WEB] Learn More About Vagus Nerve Stimulation and the Disorders It Treats

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Epilepsy, REHABILITATION on April 15, 2023

Vagus nerve stimulation was initially approved to treat drug-resistant epilepsy. Now it is also used for migraine, cluster headache, and stroke rehabilitation.

Isla Ritchie was diagnosed with epilepsy in 2014 when she was 11. Her neurologist prescribed various medications to control her tonic-clonic and absence seizures, but she continued to have breakthrough events. During an absence seizure, she would stare blankly into space for a few minutes before returning to her normal alertness without knowing what she had missed. Ritchie’s tonic-clonic seizures were more disruptive: Her limbs would shake, her muscles would stiffen, and she’d lose consciousness. If she was standing, she would fall. Sometimes a seizure would last more than five minutes, and she’d need rescue medication to stop it.

Ritchie and her parents investigated whether she could have brain surgery, but she wasn’t a candidate due to seizure activity on both sides of her brain. In 2015, however, the family, who live in Houston, learned about vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), a procedure in which a device is implanted in the chest to stimulate the vagus nerve—which runs from the brainstem through the neck to the chest and stomach—with electrical impulses. They decided to try it along with Ritchie’s antiseizure medication regimen.

After surgeons implanted the device in October 2015 and fine-tuned the stimulation over six months, Ritchie’s seizures gradually tapered off. Four years have passed since her last one. “I can’t even compare my quality of life to how it was in middle school,” says Ritchie, now 19 and a first-year student at Baylor University in Waco, TX. “Back then, my head felt so fuzzy I couldn’t process things. Now I feel like a 10 out of 10. I’ve come a long way, and I no longer worry every day about having a seizure.”

Life-Changing Treatment

The vagus nerves—one on each side of the neck—are part of the parasympathetic nervous system, often called the “rest and digest” system because it helps the body relax after periods of stress or danger and regulates bodily functions such as digestion and heart rate. The vagus nerves provide a bridge between the brain and peripheral organs, and they play an important role in memory, emotion, and pain, among other bodily functions.

The idea to stimulate the vagus nerve in people with neurologic disorders came from a researcher who experimented on animals with hereditary seizures in the 1980s and found that VNS stopped their seizures, says George Morris, MD, MPH, FAAN, medical director for epilepsy at Ascension Medical Group in Milwaukee.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved VNS for the treatment of drug-resistant seizures in humans in 1997. Since then, the FDA has approved the procedure to treat drug-resistant depression, cluster headache and migraine, and for stroke recovery. It’s also being investigated as a treatment for multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, post-traumatic stress disorder, Parkinson’s disease, cognitive disorders, and traumatic brain injury.

Stopping Seizures

VNS for epilepsy involves a pacemaker-like device surgically implanted under the skin in the left chest area; a wire is attached to the generator, placed under the skin, and wound around the vagus nerve in the neck. The device is programmed to deliver electrical stimulation at regular intervals along the left vagus nerve to the brainstem, which then sends signals to certain areas of the brain; the person with the device doesn’t feel the stimulation.

Despite its varied applications for neurologic disorders, it isn’t clear how VNS improves these conditions. The results of an animal study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in May 2022, showed that activating the vagus nerve reduced inflammation, which contributes to many different diseases, both neurologic ones and others. VNS also may positively affect rewiring of the brain and alter the balance between activity in the sympathetic nervous system (which is responsible for the body’s fight-or-flight response) and the parasympathetic nervous system.

VNS is used in addition to medication for people with epilepsy. “The goal is to reduce the number of seizures,” says Lily Wong-Kisiel, MD, FAAN, a pediatric epileptologist and associate professor of neurology at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN. It also may allow people to decrease the dose of their antiseizure medication.

Although it doesn’t cure epilepsy, VNS appears to become more effective at reducing seizures over time, unlike pharmacological therapies, says Dr. Morris. A study published in Neurosurgery in 2016 involving 5,554 people with intractable epilepsy on the VNS therapy patient outcome registry found that within the first four months of having the VNS device implanted, 49 percent of people saw a reduction in their seizure frequency, while 63 percent experienced a drop in seizures two to four years after having it implanted.

To manage seizures, VNS can be set on three modes: normal, auto-stimulation, and magnet. In normal mode, the device delivers electrical stimulation at regular intervals, so the person doesn’t need to do anything. Auto-stimulation mode, available on newer devices, delivers an extra dose of stimulation based on an increase in heart rate. “Heart rate goes up in many people with epilepsy during and sometimes before a seizure,” Dr. Wong-Kisiel says. The additional stimulation may stop a seizure or shorten it once it’s underway.

Swiping a magnet across the implanted generator to activate the stimulation is another way to disrupt a seizure. This is especially helpful for people who have an aura—a warning or a sense that a seizure is imminent—that precedes a seizure. “The magnetic activation stops or shortens a seizure two-thirds of the time,” says Angus Wilfong, MD, professor and chief of pediatric neurology at the Barrow Neurological Institute at Phoenix Children’s Hospital and professor of child health and neurology at the University of Arizona College of Medicine–Phoenix.

VNS can cause temporary changes in the voice—making it sound hoarse or raspy—when the stimulator fires. But these are fleeting side effects and usually lessen over time, says Dr. Wilfong, adding that unlike antiseizure medications, VNS does not cause weight loss or gain.

In 2013, the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) updated its guideline for using VNS to treat epilepsy, stating that it may be considered adjunctive treatment for children with partial or generalized epilepsy. The guideline also notes that in adults having the procedure, an improvement in mood may be an additional benefit.

Overall, VNS may be considered progressively effective in patients over multiple years of use. In July 2022, the AAN reaffirmed the guideline.

Easing Headache Attacks

Anna Williams, 47, has had migraine since she was a kid and developed cluster headache (an abrupt headache with an excruciating burst of pain that occurs in groups or clusters before temporarily going away) in 2013, which became chronic in 2017. She tried different medications for her migraine and cluster attacks but ended up with mood side effects she couldn’t tolerate. Eventually, she found some relief with a newer type of drug, which helped reduce the duration of the headaches, but she wanted more relief.

In May 2021, Williams found out about a handheld, noninvasive VNS device called gammaCore, which delivers self-administered electrical stimulation through the skin to either the right or left branch of the vagus nerve in the neck. She began using it twice a day to prevent cluster headaches, and within three months her chronic attacks disappeared.

“Initially, I was so focused on the cluster headaches that I didn’t consider gammaCore for migraine,” says Williams, a mother of two teenagers in New Albany, IN. “Once the clusters were in remission, I was able to get my migraine under control by using gammaCore preventively.” Williams had cluster attacks mostly on the left side of her head and migraine attacks mostly on the right, so she began using the device on both sides of her neck three times a day.

A noninvasive portable device like gammaCore can prevent or weaken a migraine or cluster headache when it is held against the side of the neck so electrical stimulation can be delivered through the skin. “It can be applied to either side [of the neck], and the person can control the intensity of the stimulation,” says Deborah I. Friedman, MD, MPH, FAAN, a neurologist and neuro-ophthalmologist in Dallas.

A study in a 2018 issue of the Journal of Headache and Pain found that these devices were significantly more effective than a sham device (acting as a placebo) in reducing the pain of migraine attacks. And in a review of studies published in a 2018 issue of the Journal of Pain Research, investigators found that VNS led to a significant reduction in pain and a decrease in the duration of cluster attacks compared with sham stimulation.

“The stimulation seems to decrease pain signaling and dampen the sympathetic activity in the nervous system, which plays a role in migraine and cluster headaches and supports parasympathetic activity,” says Robert Cowan, MD, FAAN, professor of neurology and neurological sciences at Stanford University School of Medicine in California. “It also helps protect the brain from something called cortical spreading depression, which is like a slow-moving wave of altered brain activity that causes changes in nerve firing and blood vessel function and plays a role in migraine with aura.” When it’s used preventively for chronic migraine or cluster headaches, people see a significant decrease in the number of headache days per month, Dr. Cowan says.

Doctors typically prescribe the device for people whose migraine and cluster headache attacks don’t respond to medication or who can’t tolerate the medications, Dr. Cowan says. In other cases, neurologists prescribe them in conjunction with medication.

Noninvasive VNS has no side effects and can be used during pregnancy and in children, Dr. Friedman says. But it’s expensive and often not covered by insurance. GammaCore, for example, can cost $200 a month for those paying out of pocket. The manufacturer, however, has a patient assistance program to help eligible patients pay for the device.

“It’s important for people to know these types of devices are out there,” Dr. Cowan says. “The challenge is paying for them. We would use them more if they weren’t so expensive or if they were covered by insurance.”

Boosting Stroke Rehab

In one of its newer applications, VNS may enhance stroke recovery. “It has huge effects, but we aren’t sure why,” says A.M. Barrett, MD, FAAN, chair of neurology at the UMass Chan Medical School and UMass Memorial Health Care System and chief of neurology at the VA Central Western Massachusetts Healthcare System.

A study in a 2021 issue of The Lancet investigated the effects of VNS therapy on people who had lost arm function as a result of an ischemic stroke. Those who did VNS therapy along with rehabilitation three times a week for six weeks saw twice the level of improvement in their arm function compared with those who received a sham stimulation along with their rehabilitation. “When you stimulate this nerve in the neck, it sends impulses through the brain that make it more amenable to rewiring and plasticity [reorganization],” says study co-author Steven C. Cramer, MD, FAAN, professor of neurology at UCLA and medical director of research at the California Rehabilitation Institute in Los Angeles. “Combining vagus nerve stimulation with occupational or physical therapy may result in more brain remodeling and improvements in behavior,” Dr. Cramer says.

The therapy can begin six months after a stroke, once acute inflammation has healed, and there’s no upper limit to how long after the stroke it can begin, says Michelle P. Lin, MD, MPH, a stroke neurologist at Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, FL.

In another new development, research suggests that a noninvasive VNS device placed on the skin of the ear may modulate activity in the vagus nerve after stroke. A study in a 2022 issue of Neural Regeneration Research found that when people who had had an ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke used this device along with conventional rehabilitation, they experienced significant improvement in their motor and sensory functions and emotional responses compared with the control group that had been given a sham transcutaneous VNS device with conventional rehabilitation.

Dr. Barrett is excited about the possibilities of VNS for stroke rehabilitation, especially since the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that fewer than four out of 10 stroke survivors pursue or receive outpatient therapy. Experts say VNS also may help ease depression and improve cognitive skills and leg movements after a stroke. “I’ve seen people recover from drug-resistant depression with the use of VNS,” says Dr. Barrett. “And I’ve seen it help with depression-related cognitive symptoms.”

It certainly has helped Anna Williams and Isla Ritchie. Williams says VNS put her cluster headache attacks into remission, and she has had only one migraine since July 2022. “It gave me my life back in so many ways,” Williams says. “By using the newer medication with the gammaCore, I can now be more involved in my children’s lives. I can go for daily walks with them, and I can travel again.”

These days, Ritchie, who lives on Baylor’s campus, belongs to the Honor Society as well as numerous clubs and a sorority. She’s also a dancer, choreographer, and entrepreneur: She and her mother launched a business called Go Bag, which contains necessities for unexpected trips to the ER. “VNS changed my life in a really positive way,” Ritchie says. “I can live my own dream and not be dependent on my parents.”