-

1.Pfurtscheller, G., Mcfarland, D.: BCIs that use sensorimotor rhythms. In: Wolpaw, J.R., Wolpaw, E. (eds.) Brain-Computer Interfaces: Principles and Practice, pp. 227–240. Oxford University Press (2012)Google Scholar

-

2.Carrere, L.C., Tabernig, C.B.: Detection of foot motor imagery using the coefficient of determination for neurorehabilitation based on BCI technology. IFMBE Proc. 49, 944–947 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-13117-7_239CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

3.Sannelli, C., Vidaurre, C., Müller, K.R., Blankertz, B.: A large scale screening study with a SMR-based BCI: categorization of BCI users and differences in their SMR activity (2019)Google Scholar

-

4.Do, A.H., Wang, P.T., King, C.E., Schombs, A., Cramer, S.C., Nenadic, Z.: Brain-computer interface controlled functional electrical stimulation device for foot drop due to stroke, pp. 6414–6417 (2012)Google Scholar

-

5.Ramos-Murguialday, A., Broetz, D., Rea, M., Yilmaz, Ö., Brasil, F.L., Liberati, G., Marco, R., Garcia-cossio, E., Vyziotis, A., Cho, W., Cohen, L.G., Birbaumer, N.: Brain-Machine-interface in chronic stroke rehabilitation: a controlled study. Ann. Neurol. 74, 100–108 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.23879.Brain-Machine-InterfaceCrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

6.Biasiucci, A., Leeb, R., Iturrate, I., Perdikis, S., Al-Khodairy, A., Corbet, T., Schnider, A., Schmidlin, T., Zhang, H., Bassolino, M., Viceic, D., Vuadens, P., Guggisberg, A.G., Millán, J.D.R.: Brain-actuated functional electrical stimulation elicits lasting arm motor recovery after stroke. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–13 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04673-zCrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

7.Tabernig, C.B., Lopez, C.A., Carrere, L.C., Spaich, E.G., Ballario, C.H.: Neurorehabilitation therapy of patients with severe stroke based on functional electrical stimulation commanded by a brain computer interface. J. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. Eng. 5, 205566831878928 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1177/2055668318789280CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

8.McCrimmon, C.M., King, C.E., Wang, P.T., Cramer, S.C., Nenadic, Z., Do, A.H.: Brain-controlled functional electrical stimulation therapy for gait rehabilitation after stroke: a safety study. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 12 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-015-0050-4

-

9.g.Nautilus wireless biosignal acquisition Homepage. http://www.gtec.at/Products/Hardware-and-Accessories/g.Nautilus-Specs-Features

-

10.Emotiv EpocFlex flexible wireless EEG system Homepage. https://www.emotiv.com/epoc-flex/

-

11.Vuckovic, A., Wallace, L., Allan, D.: Hybrid brain-computer interface and functional electrical stimulation for sensorimotor training in participants with tetraplegia: a proof-of-concept study. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 39, 3–14 (2015)CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

12.Schalk, G., McFarland, D.J., Hinterberger, T., Birbaumer, N., Wolpaw, J.R.: BCI2000: a general-purpose brain-computer interface (BCI) system. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 51, 1034–1043 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2004.827072CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

13.McCrimmon, C.M., Fu, J.L., Wang, M., Lopes, L.S., Wang, P.T., Karimi-Bidhendi, A., Liu, C.Y., Heydari, P., Nenadic, Z., Do, A.H.: Performance assessment of a custom, portable, and low-cost brain-computer interface platform. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 64, 2313–2320 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2017.2667579CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Posts Tagged gait rehabilitation

[ARTICLE] Immersive Virtual Reality during Robot-Assisted Gait Training: Validation of a New Device in Stroke Rehabilitation – Full Text

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Gait Rehabilitation - Foot Drop, Rehabilitation robotics, Virtual reality rehabilitation on December 14, 2022

Abstract

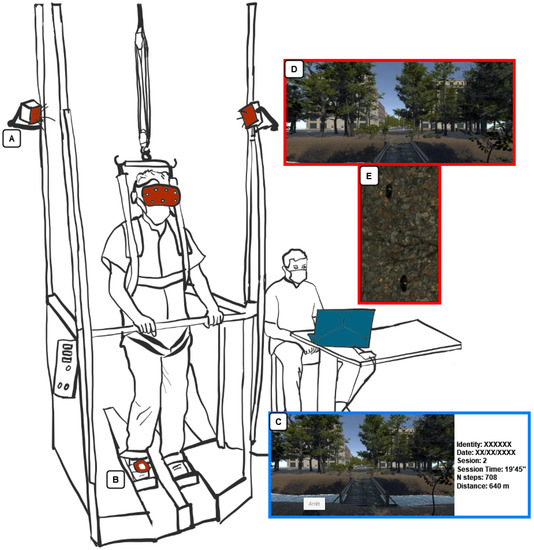

Background and objective: Duration of rehabilitation and active participation are crucial for gait rehabilitation in the early stage after stroke onset. Virtual reality (VR) is an innovative tool providing engaging and playful environments that could promote intrinsic motivation and higher active participation for non-ambulatory stroke patients when combined with robot-assisted gait training (RAGT). We have developed a new, fully immersive VR application for RAGT, which can be used with a head-mounted display and wearable sensors providing real-time gait motion in the virtual environment. The aim of this study was to validate the use of this new device and assess the onset of cybersickness in healthy participants before testing the device in stroke patients.

Materials and Methods: Thirty-seven healthy participants were included and performed two sessions of RAGT using a fully immersive VR device. They physically walked with the Gait Trainer for 20 min in a virtual forest environment. The occurrence of cybersickness, sense of presence, and usability of the device were assessed with three questionnaires: the Simulator Sickness Questionnaire (SSQ), the Presence Questionnaire (PQ), and the System Usability Scale (SUS).

Results: All of the participants completed both sessions. Most of the participants (78.4%) had no significant adverse effects (SSQ < 5). The sense of presence in the virtual environment was particularly high (106.42 ± 9.46). Participants reported good usability of the device (86.08 ± 7.54).

Conclusions: This study demonstrated the usability of our fully immersive VR device for gait rehabilitation and did not lead to cybersickness. Future studies should evaluate the same parameters and the effectiveness of this device with non-ambulatory stroke patients.

1. Introduction

Stroke is a leading cause of disability considering that 63% of patients have no independent walking function on admission to rehabilitation and this rate is 36% at discharge of hospitalization [1]. About 80% of stroke patients experience altered walking abilities 3 months after onset [2]. Walking disorders can result from deficits in muscle strength, motor control, and balance [2,3]. As a result, early recovery of walking abilities is a major concern for stroke patients insofar as it is a determining activity for autonomy, social participation, and quality of life [4]. Gait rehabilitation for stroke patients needs to start as early as possible to promote the recovery of walking ability [5]. Among the different approaches to gait rehabilitation, robot-assisted gait training (RAGT) is specifically offered to non-ambulatory patients, providing a complex gait cycle with body weight support [6].

RAGT appears to provide task-specific rehabilitation without delay and with more intensity than conventional methods [7] and may therefore promote brain plasticity [8]. The use of RAGT has been shown to improve the effectiveness of gait rehabilitation after stroke [6,7].

However, a lack of motivation and entertainment can lead to decreased rehabilitation time and RAGT effectiveness [9]. To improve the playfulness and adherence of patients during RAGT, several studies have investigated the use of non-immersive virtual reality (VR) such as flat screens [9,10,11]. They showed high acceptability and motivation [9], improved dual task performance [10], and increased balance and gait capabilities [11]. The use of non-immersive VR with RAGT has led to motor performance improvement associated with neural plasticity [11]. In addition, a higher level of immersion could increase the intrinsic motivation to participate, reduce the perceived time spent in rehabilitation, and refocus the patient on the task by reducing distractors [12,13].

The level of immersion varies according to VR definition, VR equipment, and virtual content [14]. VR is defined as “the use of interactive simulations created with computer hardware and software to present users with opportunities to engage in environments that appear and feel similar to real-word objects and events” [15]. This definition does not distinguish between non-immersive systems (3D environment displays on 2D monitors), semi-immersive, and fully immersive VR (e.g., head-mounted display (HMD), headset alone), which provide more highly engaging and realistic environments [14,16]. The use of controllers allows interaction in the virtual environment and improves the immersion by a sense of presence [13], which is also a psychological state in which the individuals feel that they belong to the virtual environment [17]. Sense of presence is modulated by several technical features of the VR tool such as the tracking level or field of view [13]. The degree of interaction with the environment, the fidelity and realism of the movements, and the landscape will influence the sense of presence. Embodiment within a virtual avatar can also encourage the feeling that the environment is ‘real’. It bears mentioning that embodiment in an avatar is modulated by the quality of synchronization between the avatar and the user’s actions [18]. Fully immersive VR via HMD is an innovative and playful approach that enables rehabilitation to focus on specific tasks, such as walking in controlled environments.

Few studies have investigated the use of fully immersive VR during walking tasks in neurological disease [12,19]. Winter et al. [12] designed a virtual scenario as a game to promote adherence and motivation of stroke patients during treadmill sessions with a playful scenario for ambulatory patients. Kim et al. [19] used a headset alone to propose a virtual city scene to older adults and individuals with Parkinson’s disease during treadmill training. They found good acceptability without alteration of balance abilities after each VR session. In addition, the level of stress was lower after exposure to the virtual environment. These studies focusing on ambulatory patients support the use of fully immersive VR in gait rehabilitation [12,19].

However, some users may develop symptoms such as motion sickness, also known as “cybersickness”. At present, the mechanisms involved in cybersickness are not yet fully understood and different theories have been proposed [20,21]. Cybersickness may be due to a sensory conflict between the signals that provide information on orientation and body movement. Since users are not actually moving, their proprioceptive and vestibular organs fail to provide movement cues and lead to sensory mismatches [22]. The virtual environments with the lowest occurrence of side effects are those using physical displacement (linked to the individual’s movements) in a scene with little visual stimulation [23].

Today, there is no fully immersive VR rehabilitation device combined with RAGT suitable for non-ambulatory stroke patients and which could promote patient adherence and active participation due to the presence of biofeedback and its playful aspect [12]. It appears very interesting to develop a new device that offers high-quality immersion and gait simulation to promote patient adherence while reducing the risk of side effects. The aim of this work was to create a new gait rehabilitation device using RAGT and fully immersive VR and to assess the sense of presence, side effects, and the usability in healthy participants.

2. Materials and Methods

Thirty-eight healthy people (20 women) among physiotherapy students and healthcare professionals were recruited for this study. The inclusion criteria were as follows: adults (>18 years old) and having completed a Motion Sickness Susceptibility Questionnaire Short Form (MSSQ-Short) ≤ 26 in order not to involve individuals susceptible to developing motion sickness [24,25]. The exclusion criteria were: (i) pathologies that do not allow use of VR (cerebellar, vestibular, and epileptic disorders) and (ii) significant visual or visual–perceptual deficits. All of the subjects gave their informed consent to participate in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the University Hospital Center of Poitiers (N° F20220719114034) on 19 July 2022.

2.1. Robot-Assisted Gait Training and VR-Device

We used the RAGT device Gait Trainer (GT) GT1 (Reha-Stim® Medtec Inc. New York, NY, USA), which is a complex gear system providing a gait-like movement with two footplates and partial or total body weight support [26]. It simulates the stance and swing phase with a ratio of 60% to 40% between the two phases and allows velocity adjustment (from 0.14 to 1.1 m/s). It provides a controlled propulsion system that adjusts its output according to the patient’s effort and manages the control of the center of mass. [26].

We developed an application with Unity software (Unity Technologies®, San Francisco, CA, USA) on a Microsoft Windows 10-based computer system that includes an i7-8750H processor, 16 GB DDR4-RAM, and an Nvidia GeForce GTX 1060. The study used a fully immersive VR experience by HMD HTC® Vive (HTC Co., New Taipei City, China) which tracked movements through sensors placed on the user’s body which could be easily adapted to any type of widely used RAGT device (Figure 1). HTC Vive has a resolution of 2160 × 1200, a refresh rate of up to 90 Hz, and a 110° field of view. In addition to gait rehabilitation, a RAGT helps to reduce the workload of physiotherapists [27], which is why it was essential to create a VR device easy and rapid to install and use (“plug and play” system). In addition, our VR device is quick to install, as the base stations can be directly fixed on the device (Figure 1A) or with wall mounts. Once installed, it only takes a few seconds to set up and remove from the user.

[Thesis] Randomized, Clinical Trials on the Effects of Robotic-Assisted Gait Training for Stroke Subjects: A Scoping Review – PDF File

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Gait Rehabilitation - Foot Drop, Rehabilitation robotics on June 8, 2022

Abstract

Robotic-assisted gait training has been cited as a potential rehabilitation intervention for the recovery of ambulation in hemiplegic stroke patients. Previous reviews on robotic gait training have elicited a need for more randomized, clinical studies on robotic gait training for the development of evidence-based intervention protocols and elimination of research bias. The purpose of this scoping review was to provide an updated examination of the clinical research on robotic assisted gait training and address any research gaps to be considered for future research. This review included randomized, clinical trials on stroke patients with a robotic-assisted treatment (RAGT) and conventional gait training (CGT) group. This review included studies observing the following outcome measures: Functional Ambulatory Category, Gait Speed, 6-minute Walking Test, Berg Balance Scale, Fugl-Meyer Assessment, and Modified Ashworth Scale. Screening on Web of Science and PubMed revealed 11 studies for review from an initial pool of 231 unique titles. Studies focused on subacute stroke patients, non-ambulatory subjects, and longer intervention protocols were more likely to observe clinically meaningful improvements in outcome. RAGT groups were more likely to observe greater improvements in outcome than CGT groups. However, individual studies observed relatively few significant differences between treatment groups. Clinical trials on robotic-assisted gait training for stroke patients were at different stages in research, based on the assistive device in question. Future clinical trials should focus on cost-effectiveness of RAGT, proper intervention dosage, and personalization of RAGT based on stroke subject characteristics.

Rights

In Copyright. URI: http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ This Item is protected by copyright and/or related rights. You are free to use this Item in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s).

Persistent Identifier

[ARTICLE] Systematic review on wearable lower-limb exoskeletons for gait training in neuromuscular impairments – Full Text

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Gait Rehabilitation - Foot Drop, REHABILITATION, Rehabilitation robotics on March 4, 2021

Abstract

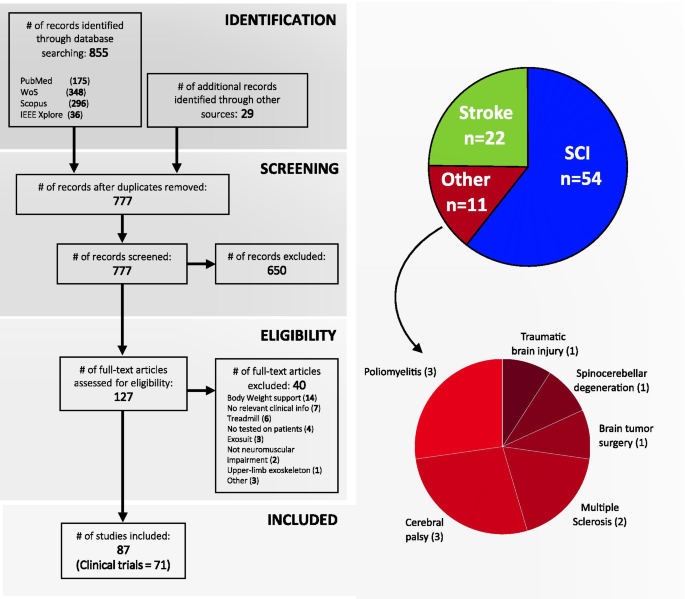

Gait disorders can reduce the quality of life for people with neuromuscular impairments. Therefore, walking recovery is one of the main priorities for counteracting sedentary lifestyle, reducing secondary health conditions and restoring legged mobility. At present, wearable powered lower-limb exoskeletons are emerging as a revolutionary technology for robotic gait rehabilitation. This systematic review provides a comprehensive overview on wearable lower-limb exoskeletons for people with neuromuscular impairments, addressing the following three questions: (1) what is the current technological status of wearable lower-limb exoskeletons for gait rehabilitation?, (2) what is the methodology used in the clinical validations of wearable lower-limb exoskeletons?, and (3) what are the benefits and current evidence on clinical efficacy of wearable lower-limb exoskeletons? We analyzed 87 clinical studies focusing on both device technology (e.g., actuators, sensors, structure) and clinical aspects (e.g., training protocol, outcome measures, patient impairments), and make available the database with all the compiled information. The results of the literature survey reveal that wearable exoskeletons have potential for a number of applications including early rehabilitation, promoting physical exercise, and carrying out daily living activities both at home and the community. Likewise, wearable exoskeletons may improve mobility and independence in non-ambulatory people, and may reduce secondary health conditions related to sedentariness, with all the advantages that this entails. However, the use of this technology is still limited by heavy and bulky devices, which require supervision and the use of walking aids. In addition, evidence supporting their benefits is still limited to short-intervention trials with few participants and diversity among their clinical protocols. Wearable lower-limb exoskeletons for gait rehabilitation are still in their early stages of development and randomized control trials are needed to demonstrate their clinical efficacy.

Background

Gait disorders affect approximately 60% of patients with neuromuscular disorders [1] and generally have a high impact on their quality of life [2]. Moreover, immobility and loss of independence for performing basic activities of daily living results in patients being restricted to a sedentary lifestyle. This lack of physical activity increases the risk of developing secondary health conditions (SHCs), such as respiratory and cardiovascular complications, bowel/bladder dysfunction, obesity, osteoporosis and pressure ulcers [3,4,5,6,7]; which can further reduce the patients’ life expectancy [3, 4]. Therefore, walking recovery is one of the main rehabilitation goals for patients with neuromuscular impairments [8, 9].

Robotic gait rehabilitation appeared 25 years ago as an alternative to conventional manual gait training. Compared with conventional therapy, robotic gait rehabilitation can deliver highly controlled, repetitive and intensive training in an engaging environment [10], reduce the physical burden for the therapist, and provide objective and quantitative assessments of the patients’ progression [11]. The use of gait rehabilitation robots began in 1994 [12] with the development of Lokomat [13]. Since then, different rehabilitation robots have been developed and can be classified into grounded exoskeletons (e.g., Lokomat [14], LOPES [15], ALEX [16]), end-effector devices (e.g., Gait Trainer [17], Haptic Walker [18]), and wearable exoskeletons (e.g., ReWalk [19], Ekso [20], Indego [21]) [12]. In addition, there have been recent developments towards “soft exoskeletons” or “exosuits” which use soft actuation systems and/or structures to assist the walking function [22,23,24,25]. Despite these developments, to date the optimal type of rehabilitation robot for a specific user and neuromuscular impairment still remains unclear [26].

Wearable exoskeletons are emerging as revolutionary devices for gait rehabilitation due to both the active participation required from the user, which promotes physical activity [27], and the possibility of being used as an assistive device in the community. The number of studies on wearable exoskeletons during the past 10 years has seen a rapid increase, following the general tendency now towards rehabilitation robots [28]. Some of these devices already have FDA approval and/or CE mark, and are commercially available, whereas many others are still under development.

There have been several reviews surveying the field of wearable exoskeletons for gait rehabilitation. Some of these reviews have focused on reviewing the technological aspects of exoskeletons from a general perspective [29, 30], while others have focused on specific aspects such as the control strategies [31] or the design of specific joints [32]. A selection of reviews have focused on surveying the evidence on effectiveness and usability of exoskeletons for clinical neurorehabilitation in general [33, 34], or for a specific pathology such as spinal cord injury (SCI) [30, 34] or stroke [11].

This review provides a comprehensive overview on wearable lower-limb powered exoskeletons for over ground training, without body weight support, that are intended for use with people who have gait disorders due to neuromuscular impairments. In comparison with other reviews, we analyse a wide range of aspects of wearable exoskeletons, from their technology to their clinical evidence, for different types of pathologies. This systematic review was carried out to address the following questions: (1) what is the current technological status of wearable lower-limb exoskeletons for gait rehabilitation?, (2) what are the benefits and risks for exoskeleton users?, and (3) what is the current evidence on clinical efficacy for wearable exoskeletons?

[ARTICLE] Evaluating the effect of immersive virtual reality technology on gait rehabilitation in stroke patients: a study protocol for a randomized controlled trial – Full Text

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Gait Rehabilitation - Foot Drop, REHABILITATION, Virtual reality rehabilitation on January 29, 2021

Abstract

Background

The high incidence of cerebral apoplexy makes it one of the most important causes of adult disability. Gait disorder is one of the hallmark symptoms in the sequelae of cerebral apoplexy. The recovery of walking ability is critical for improving patients’ quality of life. Innovative virtual reality technology has been widely used in post-stroke rehabilitation, whose effectiveness and safety have been widely verified. To date, however, there are few studies evaluating the effect of immersive virtual reality on stroke-related gait rehabilitation. This study outlines the application of immersive VR-assisted rehabilitation for gait rehabilitation of stroke patients for comparative evaluation with traditional rehabilitation.

Methods

The study describes a prospective, randomized controlled clinical trial. Thirty-six stroke patients will be screened and enrolled as subjects within 1 month of initial stroke and randomized into two groups. The VRT group (n = 18) will receive VR-assisted training (30 min) 5 days/week for 3 weeks. The non-VRT group (n = 18) will receive functional gait rehabilitation training (30 min) 5 days/week for 3 weeks. The primary outcomes and secondary outcomes will be conducted before intervention, 3 weeks after intervention, and 6 months after intervention. The primary outcomes will include time “up & go” test (TUGT). The secondary outcomes will include MMT muscle strength grading standard (MMT), Fugal-Meyer scale (FMA), motor function assessment scale (MAS), improved Barthel index scale (ADL), step with maximum knee angle, total support time, step frequency, step length, pace, and stride length.

Discussion

Virtual reality is an innovative technology with broad applications, current and prospective. Immersive VR-assisted rehabilitation in patients with vivid treatment scenarios in the form of virtual games will stimulate patients’ interest through active participation. The feedback of VR games can also provide patients with performance awareness and effect feedback, which could be incentivizing. This study may reveal an improved method of stroke rehabilitation which can be helpful for clinical decision-making and future practice.

Background

Stroke is a serious disease with a high disability rate. Often occurring in elderly populations, stroke-related disability contributes one of the main causes of adult disability [1]. Studies show that stroke survivors experience residual physical dysfunction which has a great impact on their ability to live. Studies have reported that 55–80% of stroke survivors demonstrate continuous motor dysfunction, decreased quality of life, and limited activities in daily life [1,2,3,4]. Other studies have reported that 80% of stroke patients experience movement disorders, including loss of balance and gait ability [1, 3]. The disease-related movement disorders and the subsequent decrease in daily living activity can be a great burden to patients, their families, and society. Gait disorder is one of the most common symptoms in stroke sequelae; thus, the recovery of walking ability is the key to improving patients’ self-care ability and quality of life. Compared with that of the healthy people, the gait of patients with cerebral apoplexy often manifests as slowed, shortened standing time on the paralyzed side, too early toes falling when standing, etc. [5]. As such, gait rehabilitation is often the primary goal of stroke rehabilitation [6,7,8]. As the population continues to age, an increasing number of stroke patients are posed to experience great challenges to disease-related effects. In turn, improving the efficiency of rehabilitation strategies remains of paramount importance.

Virtual reality (VR) is an innovative tool to realize connection, operation, and interaction between human vision and computer-simulated scenarios [9]. Non-immersive VR (for example Xbox Kinect) has been applied in clinical trials of stroke rehabilitation [10, 11]. VR training experience is interesting and enjoyable for the patient, which reduces fatigue, keeps patients in a happy mood, and reduces the boredom of repetitive, conventional rehabilitation. Non-immersive VR-assisted rehabilitation is proposed to provide a more personalized intervention therapy [12]. VR training for stroke patients can therefore improve the participation and autonomy of patients in the rehabilitation process, qualities that have been shown to be more cost and resource effective [13]. Overall, non-immersive VR has been shown to increase limb function learning and improves the quality of life [14].

Recently, immersive VR is a novel VR type. Immersive VR involves a head-mounted display with visual and auditory cues and controllers using haptic (sense of touch) feedback in a 3-dimensional environment [15]. Immersive VR is a technology that provides more realistic environment scene design and object tracking than previous ordinary VR [16], which provides virtual interaction and real-time feedback in vision, touch, hearing, and even motion in realistic scenarios. Patients can experience controllable movement or operation in a simulated virtual environment, so as to achieve the rebuilding or restoring of physical functions.

Immersive VR researches have been reported in the field of pain medicine [17]. In the field of post-stroke rehabilitation, immersive VR has also been reported in upper limb motor function and cognitive ability [16, 18]. However, a few studies have previously explored the application of immersive VR-assisted training in gait rehabilitation after stroke. For example, Biffi et al. found that immersive virtual reality platform enhances the walking ability of children with acquired brain injuries [19] and research by Irene Cortes-Perez has shown that immersive virtual reality improves balance in stroke patients and reduces the risk of falls [20]. Thus, research on immersive VR-assisted training in gait rehabilitation requires its own dedicated investigation. As a VR device of reasonable cost, it has become a powerful research tool for scientific researchers [21, 22]. This study will apply the immersive device to execute VR scenes of rehabilitation training according to clinical practice, so as to systematically evaluate the application of immersive VR technology in the rehabilitation of stroke gait disorders. […]

[ARTICLE] Adaptive Treadmill-Assisted Virtual Reality-Based Gait Rehabilitation for Post-Stroke Physical Reconditioning—a Feasibility Study in Low-Resource Settings – Full Text

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Gait Rehabilitation - Foot Drop, REHABILITATION, Virtual reality rehabilitation on May 26, 2020

Abstract

Physiological Cost Index sensitive Adaptive Response Technology (PCI-ART) for post-stroke physical reconditioning. Note: PCI- Physiological Cost Index; SST-Single Support Time; AL- Affected limb; UAL- Unaffected limb.

Introduction

Neurological disorders, such as stroke is a leading cause of disability with a prevalence rate of 424 in 100,000 individuals in India [1]. Often, these patients suffer from functional disabilities, heterogeneous physical deconditioning along with deteriorated cardiac functioning [2], [3] and a sedentary lifestyle immediately following stroke [4]. A deconditioned patient requires reconditioning of his/her cardiac capacity and ambulation capabilities that can be achieved through individualized rehabilitation [5]. This needs to be done under the supervision of a clinician who can monitor one’s functional capability, cardiac capacity and gait performance thereby recommending an appropriate dosage of the gait rehabilitation exercise intensity to the patient along with feedback. Such gait rehabilitation is crucial since about 80% of these patients have been reported to suffer from gait-related disorders [6] along with more energy expenditure than able-bodied individuals [7] often accompanied with reduced cardiac capacity [2], [4]. However, given the low doctor-to-patient ratio [8], lack of rehabilitation facilities and patients being released early from rehabilitation clinics followed by home-based exercise [9], particularly in developing countries like India, availing individualized rehabilitation services becomes difficult. Again, undergoing home-based exercises under clinician’s one-on-one supervision becomes difficult given the restricted healthcare resources, thereby limiting the rehabilitation outcomes [10]. Again, given the restricted healthcare resources, getting a clinician visiting the homes for delivering therapy sessions to patients is often costly causing the patients to miss the expert inputs on the exercise intensity suiting his/her exercise capability along with motivational feedback from the clinician [11]. This necessitates the use of a complementary technology-assisted rehabilitation platform that can be availed by the patient at his/her home [12] following a short stay at the rehabilitation clinic [13]. Again, it is preferred that this platform be capable of offering individualized gait exercise while varying the dosage of exercise intensity (based on the patient’s exercise capability) along with motivational feedback [14]. Additionally, exercise administered by this platform can be complemented with intermediate clinician-mediated assessments of rehabilitation outcomes, thereby reducing continuous demands on the restricted clinical resources. Thus, it is important to investigate the use of such technology-assisted gait exercise platforms that are capable of offering exercise based on one’s individualized capability along with motivational feedback.

Researchers have explored the use of technology-assisted solutions to offer rehabilitative gait exercises to these patients, along with presenting motivational feedback [15]–[16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24]. Specifically, investigators have used Virtual Reality (VR) coupled with a treadmill (having a limited footprint and making it suitable for home-based settings) while delivering individualized feedback [15] to the patient during exercise. Again, VR can help to project scenarios that can make the exercise engaging and interactive for a user [16]–[17][18][19]. In fact, Finley et al. have shown that the visual feedback offered by VR provides an optical flow that can induce changes in the gait performance (quantified in terms of gait parameters, e.g., Step Length, Step Symmetry, etc.) of such patients during treadmill-assisted walk [20]. Further, Jaffe et al. have reported positive implications of VR-based treadmill-assisted walking exercise on the gait performance of individuals with stroke [23], leading to improvement in their community ambulation [24]. These studies have shown the efficacy of the VR-based treadmill-assisted gait exercise platform to contribute towards gait rehabilitation of individuals suffering from stroke. Though promising, none of these platforms are sensitive to one’s individualized exercise capability and thus, in turn, could not decide an optimum dosage of exercise intensity suiting one’s capability, e.g., cardiac capacity and ambulation capability. This is particularly critical for individuals with stroke since they possess diminished exercise ability along with deteriorated cardiac functioning [2], [4].

From literature review, we find that after stroke, treadmill-assisted cardiac exercise programs can lead to one’s improved fitness and exercise capability [25]. For example, researchers have presented studies on Moderate-Intensity Continuous Exercise and High-Intensity Interval Training in which exercise protocols are individualized by a clinician based on one’s cardiac capacity while contributing to effective gait rehabilitation [26]–[27][28][29]. Though promising, these have not offered a progressive and adaptive exercise environment in which the dosage of exercise intensity is varied based on one’s cardiac capacity in real-time. Thus, the choice of optimum dosage of exercise intensity that can be individualized in real-time for a patient, still remains as inadequately explored [4]. For deciding the optimal dosage of rehabilitative exercise intensity, clinicians often refer to the guidelines recommended by the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) [30]. These guidelines suggest thresholds to decide the intensity of the exercise based on one’s metabolic energy consumption in terms of oxygen intake, heart rate, etc. Deciding the dosage of exercise intensity is crucial, particularly for individuals with stroke since their energy requirements have been reported to be 55-100% higher than that of their able-bodied counterparts [7]. Specifically, higher energy requirement often limits the capabilities of these patients and challenges their rehabilitation outcomes. This can be addressed if the technology-assisted gait exercise platform can offer individualized exercise (maintaining the safe exercise thresholds) based on the energy expenditure of the patients acquired in real-time during the exercise.

The energy expenditure can be defined as the cost of physical activity [4] and it is often expressed in terms of oxygen consumption or heart rate [31]. Thus, investigators have monitored the oxygen consumption and heart rate to estimate the energy expenditure of individuals with stroke during their walk [31], [32]. However, monitoring oxygen consumption during exercise requires a cumbersome setup [31], making it unsuitable for home-based rehabilitation. On the other hand, one’s heart rate (HR) can be monitored using portable solutions [33] that can be integrated with a treadmill in home-based settings. Researchers have explored treadmill-assisted gait exercise platforms that are sensitive to the user’s heart rate. For example, researchers have offered treadmill training to subjects with stroke in which some of them varied treadmill speed to achieve 45%-50% [34], while others varied speed to achieve 85% to 95% [35], [36] of one’s age-related maximum heart rate. Again, Pohl et al. have offered treadmill-assisted exercise to subjects with stroke while ensuring that the user’s heart rate settled to the respective resting-state heart rate [37]. Again of late, there had been advanced treadmills, available off-the-shelf, that can monitor one’s heart rate and vary the treadmill speed to maintain the user’s heart rate at a predefined level [38], [39]. Though one’s heart rate is an important indicator that needs to be considered during treadmill-assisted exercise, one’s walking speed while using the treadmill also offers important information on one’s exercise capability. This is because gait rehabilitation aims to improve one’s community ambulation that is related to one’s walking speed [40]. Thus, it would be interesting to explore the composite effect of one’s walking speed along with working and resting-state heart rates during treadmill-assisted gait exercise to study one’s energy expenditure, quantified in terms of a proxy index, namely Physiological Cost Index (PCI) [31].

Given that there are no existing studies that have used a treadmill-assisted gait exercise platform deciding the dosage of exercise intensity based on one’s PCI estimated in real-time during exercise, it might be interesting to explore the use of such an individualized gait exercise platform for individuals with stroke. Thus, we wanted to extend a treadmill-assisted gait exercise platform by making it adaptive to one’s individualized PCI. Additionally, we wanted to augment this platform with VR-based user interface to offer visual feedback to the user undergoing gait exercise. We hypothesized that such a gait exercise platform can recondition a patient’s exercise capability in terms of cardiac and gait performance to achieve improved community ambulation. The objectives of our research were three-fold, namely to (i) implement a novel PCI-sensitive Adaptive Response Technology (PCI-ART) offering VR-based treadmill-assisted gait exercise, (ii) investigate the safety and feasibility of use of this platform among able-bodied individuals before applying it to subjects with stroke and (iii) examine implications of undergoing gait exercise with this platform on the patients’ (a) cardiac and gait performance along with energy expenditure, (b) clinical measures estimating the physical reconditioning and (c) views on their community ambulation capabilities.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section II presents our system design. Section III explains the experiments and procedures of this study. Section IV discusses the results. In Section V, we summarize our findings, limitations, and scope of future research.[…]

[Abstract + References] Gait rehabilitation after stroke: review of the evidence of predictors, clinical outcomes and timing for interventions

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Gait Rehabilitation - Foot Drop, REHABILITATION on March 27, 2020

Abstract

The recovery of walking capacity is one of the main aims in stroke rehabilitation. Being able to predict if and when a patient is going to walk after stroke is of major interest in terms of management of the patients and their family’s expectations and in terms of discharge destination and timing previsions. This article reviews the recent literature regarding the predictive factors for gait recovery and the best recommendations in terms of gait rehabilitation in stroke patients. Trunk control and lower limb motor control (e.g. hip extensor muscle force) seem to be the best predictors of gait recovery as shown by the TWIST algorithm, which is a simple tool that can be applied in clinical practice at 1 week post-stroke. In terms of walking performance, the 6-min walking test is the best predictor of community ambulation. Various techniques are available for gait rehabilitation, including treadmill training with or without body weight support, robotic-assisted therapy, virtual reality, circuit class training and self-rehabilitation programmes. These techniques should be applied at specific timing during post-stroke rehabilitation, according to patient’s functional status.

References

- 1.

Stevens E, Emmett E, Wang Y, McKevitt C, Wolfe C (2018) The burden of stroke in Europe, report. Division of Health and Social Care Research, King’s College London, London

- 2.

Jorgensen HS, Nakayama H, Raaschou HO, Olsen TS (1995) Recovery of walking function in stroke patients: the Copenhagen Stroke Study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 76(1):27–32

- 3.

Harvey RL (2015) Predictors of functional outcome following stroke. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 26(4):583–598

- 4.

WHO (2007) International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health: Children & Youth Version: ICF-CY. World Health Organization

- 5.

Kinoshita S, Abo M, Okamoto T, Tanaka N (2017) Utility of the revised version of the ability for basic movement scale in predicting ambulation during rehabilitation in poststroke patients. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis Off J Natl Stroke Assoc 26(8):1663–1669

- 6.

KNGF (2014) KNGF guidelines: stroke. Royal Dutch Society for Physical Therapy (Koninklijk Nederlands Genootschap voor Fysiotherapie, KNGF)

- 7.

Holsbeeke L, Ketelaar M, Schoemaker MM, Gorter JW (2009) Capacity, capability, and performance: different constructs or three of a kind? Arch Phys Med Rehabil 90(5):849–855

- 8.

Perry J, Garrett M, Gronley JK, Mulroy SJ (1995) Classification of walking handicap in the stroke population. Stroke 26(6):982–989

- 9.

Smith MC, Barber PA, Stinear CM (2017) The TWIST algorithm predicts time to walking independently after stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 31(10–11):955–964

- 10.

Winstein CJ, Stein J, Arena R, Bates B, Cherney LR, Cramer SC et al (2016) Guidelines for adult stroke rehabilitation and recovery: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 47(6):e98–e169

- 11.

Platz T (2019) Evidence-based guidelines and clinical pathways in stroke rehabilitation—an international perspective. Front Neurol 10:200

- 12.

Kollen B, Kwakkel G, Lindeman E (2006) Longitudinal robustness of variables predicting independent gait following severe middle cerebral artery stroke: a prospective cohort study. Clin Rehabil 20(3):262–326

- 13.

Veerbeek JM, Van Wegen EE, Harmeling-Van der Wel BC, Kwakkel G (2011) Is accurate prediction of gait in nonambulatory stroke patients possible within 72 hours poststroke? The EPOS study. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 25(3):268–274

- 14.

Stinear CM, Byblow WD, Ward SH (2014) An update on predicting motor recovery after stroke. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 57(8):489–498

- 15.

Collin C, Wade D (1990) Assessing motor impairment after stroke: a pilot reliability study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 53(7):576–579

- 16.

Fulk GD, He Y, Boyne P, Dunning K (2017) Predicting home and community walking activity poststroke. Stroke 48(2):406–411

- 17.

Duncan PW, Sullivan KJ, Behrman AL, Azen SP, Wu SS, Nadeau SE et al (2011) Body-weight-supported treadmill rehabilitation after stroke. N Engl J Med 364(21):2026–2036

- 18.

Kluding PM, Dunning K, O’Dell MW, Wu SS, Ginosian J, Feld J et al (2013) Foot drop stimulation versus ankle foot orthosis after stroke: 30-week outcomes. Stroke 44(6):1660–1669

- 19.

Tudor-Locke C, Bassett DR Jr (2004) How many steps/day are enough? Preliminary pedometer indices for public health. Sports Med (Auckl NZ) 34(1):1–8

- 20.

Friedman PJ (1990) Gait recovery after hemiplegic stroke. Int Disabil Stud 12(3):119–122

- 21.

Bland MD, Sturmoski A, Whitson M, Connor LT, Fucetola R, Huskey T et al (2012) Prediction of discharge walking ability from initial assessment in a stroke inpatient rehabilitation facility population. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 93(8):1441–1447

- 22.

Jones PS, Pomeroy VM, Wang J, Schlaug G, Tulasi Marrapu S, Geva S et al (2016) Does stroke location predict walk speed response to gait rehabilitation? Hum Brain Mapp 37(2):689–703

- 23.

Yelnik AP, Quintaine V, Andriantsifanetra C, Wannepain M, Reiner P, Marnef H et al (2017) AMOBES (Active Mobility Very Early After Stroke): a randomized controlled trial. Stroke 48(2):400–405

- 24.

Bernhardt J, Langhorne P, Lindley RI, Thrift AG, Ellery F, Collier J et al (2015) Efficacy and safety of very early mobilisation within 24 h of stroke onset (AVERT): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet (Lond Engl) 386(9988):46–55

- 25.

Stroke Foundation (2019) Clinical Guidelines for Stroke Management. Melbourne Australia

- 26.

Mehrholz J, Thomas S, Elsner B (2017) Treadmill training and body weight support for walking after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002840.pub3

- 27.

Flansbjer UB, Holmback AM, Downham D, Patten C, Lexell J (2005) Reliability of gait performance tests in men and women with hemiparesis after stroke. J Rehabil Med 37(2):75–82

- 28.

Perera S, Mody SH, Woodman RC, Studenski SA (2006) Meaningful change and responsiveness in common physical performance measures in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 54(5):743–749

- 29.

Eng JJ, Dawson AS, Chu KS (2004) Submaximal exercise in persons with stroke: test–retest reliability and concurrent validity with maximal oxygen consumption. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 85(1):113–118

- 30.

Mehrholz J, Thomas S, Werner C, Kugler J, Pohl M, Elsner B (2017) Electromechanical-assisted training for walking after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006185.pub3

- 31.

de Rooij IJ, van de Port IG, Meijer JG (2016) Effect of virtual reality training on balance and gait ability in patients with stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys Ther 96(12):1905–1918

- 32.

Cohen J (2013) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge, London

- 33.

Faraone SV (2008) Interpreting estimates of treatment effects: implications for managed care. P T Peer Rev J Formul Manag 33(12):700–711

- 34.

English C, Hillier SL, Lynch EA (2017) Circuit class therapy for improving mobility after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007513.pub2

- 35.

Aaslund MK, Moe-Nilssen R, Gjelsvik BB, Bogen B, Naess H, Hofstad H et al (2017) A longitudinal study investigating how stroke severity, disability, and physical function the first week post-stroke are associated with walking speed six months post-stroke. Physiother Theory Pract 33(12):932–942

- 36.

Cumming TB, Thrift AG, Collier JM, Churilov L, Dewey HM, Donnan GA et al (2011) Very early mobilization after stroke fast-tracks return to walking: further results from the phase II AVERT randomized controlled trial. Stroke 42(1):153–158

- 37.

de Rooij IJM, van de Port IGL, Visser-Meily JMA, Meijer JG (2019) Virtual reality gait training versus non-virtual reality gait training for improving participation in subacute stroke survivors: study protocol of the ViRTAS randomized controlled trial. Trials 20(1):89

- 38.

Cook DJ, Mulrow CD, Haynes RB (1998) Systematic reviews: synthesis of best evidence for clinical decisions. Ann Intern Med 126(5):376–380

- 39.

Rother ET (2007) Systematic literature review × narrative review. Acta Paul Enferm 20:v–vi

[ARTICLE] Individualized feedback to change multiple gait deficits in chronic stroke – Full Text

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Gait Rehabilitation - Foot Drop, REHABILITATION on December 27, 2019

Abstract

Background

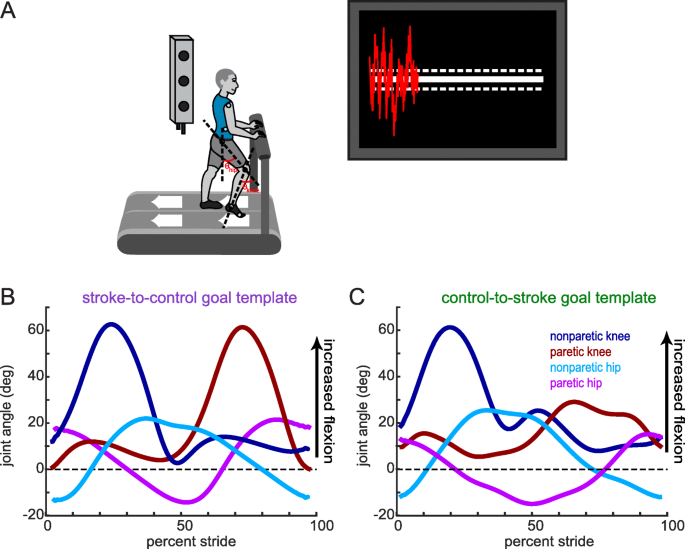

Walking deficits in people post-stroke are often multiple and idiosyncratic in nature. Limited patient and therapist resources necessitate prioritization of deficits such that some may be left unaddressed. More efficient delivery of therapy may alleviate this challenge. Here, we look to determine the utility of a novel principal component-based visual feedback system that targets multiple, patient-specific features of gait in people post-stroke.

Methods

Ten individuals with stroke received two sessions of visual feedback to attain a walking goal. This goal consisted of bilateral knee and hip joint angles of a typical ‘healthy’ walking pattern. The feedback system uses principal component analysis (PCA) to algorithmically weight each of the input features so that participants received one stream of performance feedback. In the first session, participants had to explore different patterns to achieve the goal, and in the second session they were informed of the goal walking pattern. Ten healthy, age-matched individuals received the same paradigm, but with a hemiparetic goal (i.e. to produce the pattern of an exemplar stroke participant). This was to distinguish the extent to which performance limitations in stroke were due neurological injury or the PCA based visual feedback itself.

Results

Principal component-based visual feedback can differentially bias multiple features of walking toward a prescribed goal. On average, individuals with stroke typically improved performance via increased paretic knee and hip flexion, and did not perform better with explicit instruction. In contrast, healthy people performed better (i.e. could produce the desired exemplar stroke pattern) in both sessions, and were best with explicit instruction. Importantly, the feedback for stroke participants accommodated a heterogeneous set of walking deficits by individually weighting each feature based on baseline walking.

Conclusions

People with and without stroke are able to use this novel visual feedback to train multiple, specific features of gait. Important for stroke, the PCA feedback allowed for targeting of patient-specific deficits. This feedback is flexible to any feature of walking in any plane of movement, thus providing a potential tool for therapists to simultaneously target multiple aberrant features of gait.

Background

Gait impairment following stroke often presents with multiple deficits. Some of the most common deficits include decreased paretic leg knee flexion during swing, hip circumduction, step length asymmetry, pelvic tilt, and decreased ankle dorsiflexion [1,2,3,4,5]. Unfortunately, resources (e.g. patient time/finances, therapist time, insurance coverage, etc), are limited, making it difficult to address all existing deficits in a single episode of care. Consequently, therapists are confronted with the challenge of using their clinical judgement to prioritize deficits, serially targeting those that they believe will most improve walking function and independence. Addressing one deficit in isolation of the others may introduce unintended compensations that further impair gait. Indeed, when manipulating a lower-limb movement pattern, lower-limb sagittal plane kinematics (e.g. hip/knee angles) are closely coupled [6,7,8].Thus, there remains a need for both the systematic prioritization of gait deficits and improvement in the efficiency of training so as to simultaneously address multiple patient-specific deficits.

Real-time visual feedback of gait kinematics has proven useful in altering targeted features of gait in healthy and neurological populations [9,10,11,12,13,14]. For example, Cherry-Allen et al. used visual feedback of joint angles to increase peak knee angle in people post-stroke [15]. Moreover, visual feedback has been effective in improving gait speed, stride length, and stride width in people post-stroke [16,17,18]. Still, research protocols using visual feedback of kinematic gait parameters have two prominent issues when looking to improve individual patient deficits: 1) they are focused on altering one feature of walking while leaving others unconstrained and 2) they are predicated on the assumption that the targeted parameter is the most prominent deficit for the entire group of patients included in the particular study. Given the heterogeneity of deficits following stroke, it would be most beneficial to have a system that can accommodate a wide array of walking patterns.

We developed a novel method to generate individualized, yet simple, visual feedback for re-training walking on a treadmill. An innovative element of this process is the use of principal component analysis (PCA) to display a simple ‘summary’ of a multi-dimensional movement pattern that continuously updates on a screen in front of participants as they walk. PCA has applied to motion data in a number of previous studies to characterize whole-body movement in both healthy [19, 20] and pathological populations [21,22,23,24,25]. The question that we ask here is whether this novel, PCA-based visual feedback system can address multiple, patient-specific deficits simultaneously. For stroke patients, we established a goal walking pattern that included four kinematic dimensions (bilateral hip and knee joint angles) of an average ‘healthy’ walking pattern. Each of the four kinematic dimensions was individually weighted based on a participant’s baseline deficits (defined as the difference between baseline walking and the goal walking pattern). Thus, weights varied across participants and were specific to their deficit.

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of our novel visual feedback in altering gait post-stroke. Thus, to contrast performance of participants with chronic stroke who received a control goal walking pattern (i.e. stroke-to-control), we evaluated the performance of healthy, age-matched controls who receive a hemiparetic goal walking pattern (i.e. control-to-stroke) using the same visual feedback. This contrast allows us to further validate our method by investigating the extent to which performance in stroke-to-control was limited by neurological injury compared to limitations imposed by the method itself. We hypothesized that participants in both groups would be able to use this summary visual feedback to simultaneously alter multiple aspects of their gait (albeit to varying extends depending on their impairment) toward the prescribed goal pattern while walking on a treadmill.

Methods

Participants

Ten adults with chronic stroke (3 female; age: 59.0 ± 7.4 yr) and ten group age-matched neurologically intact adults (7 female; age: 57.3 ± 6.8 yr) were recruited for this experiment. All participants with chronic stroke met inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1). All participants provided written, informed consent before taking part in the experiment. The experimental protocol was approved by the Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Clinical assessments

Participants with chronic stroke underwent clinical examination prior to the experiment. To quantify motor impairment we administered the lower extremity subscale of the Fugl-Meyer test (FM-LE) [26]. This test includes 17 items scored on an ordinal scale (0–2) with 34 possible points and higher scores representing less impairment. We measured self-selected and fastest comfortable over ground walking speeds by having participants walk two passes at each speed across a six-meter electronic walkway (Zeno Walkway, ProtoKinetics, Havertown, PA). Baseline knee and hip flexion angles, used to determine study eligibility, were measured using motion capture while participants walked on the treadmill at their self-selected speed. Participants who customarily wore an ankle-foot orthosis continued using these items throughout the study.

We also tested for sensory impairment in participants with chronic stroke. For proprioception testing, participants were supine with their eyes closed. The examiner stabilized the proximal joint segment and passively moved the distal segment to a position above or below the neutral starting position (neutral position was midway through the joint’s range of motion). The participant reported whether the position of the specified joint was above or below the starting position. Paretic hip, knee, and ankle joints were each tested at six different positions (18 total probes). Participants with stroke also completed The Star Cancellation Test, a screening tool that detects the presence of unilateral spatial neglect [27]. Scores less than 44/54 stars cancelled is suggestive of unilateral spatial neglect.

We assessed cognitive function in both participants with chronic stroke and control participants using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) [28]. Scores greater than 26/30 possible points reflect normal cognitive function.

Motion analysis

We recorded participants’ kinematics using an Optotrak Certus motion capture system (Northern Digital, Waterloo, ON) as they walked on a split-belt treadmill (Woodway, Waukesha, WI) with a separate belt for each leg. This type of treadmill allowed us to detect right and left foot contacts via distinct force plates under each belt, but the belt speeds were equal throughout all experiments. Kinematic data were collected at 100 Hz from 12 infrared-emitting diodes placed bilaterally on the foot (fifth metatarsal head), ankle (lateral malleolus), knee (lateral epicondyle), hip (greater trochanter), pelvis (iliac crest), and shoulder (acromion process; Fig. 1a).

Experimental set-up, visual feedback display and goal walking patterns. (a) Marker placement and general set up for motion capture. Bilateral, sagittal-plane hip and knee angles were calculated from the marker positions in real-time. These angles were fed into an algorithm to condense the information into a single dimension. The visual display that participants received is displayed on the right. Participants were instructed to minimize the deviation between their feedback performance (red trace) and the center white target line. Dashed lines around the target line correspond to the success zone. (b) Stroke-to-control goal template consisting of the bilateral hip and knee angles of an average control participant while walking. People post-stroke improved their performance using the visual feedback by more closely matching this set of kinematics. (c) Control-to-stroke goal template consisting of the bilateral hip and knee angles of an exemplar patient post-stroke with hemiparetic gait affecting the left side. Control participants improved their performance using the visual feedback by more closely matching this set of kinematics

[…]

[Abstract] Enriching footsteps sounds in gait rehabilitation in chronic stroke patients: a pilot study

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Gait Rehabilitation - Foot Drop, REHABILITATION on December 8, 2019

Abstract

In the context of neurorehabilitation, sound is being increasingly applied for facilitating sensorimotor learning. In this study, we aimed to test the potential value of auditory stimulation for improving gait in chronic stroke patients by inducing alterations of the frequency spectra of walking sounds via a sound system that selectively amplifies and equalizes the signal in order to produce distorted auditory feedback. Twenty‐two patients with lower extremity paresis were exposed to real‐time alterations of their footstep sounds while walking. Changes in body perception, emotion, and gait were quantified. Our results suggest that by altering footsteps sounds, several gait parameters can be modified in terms of left–right foot asymmetry. We observed that augmenting low‐frequency bands or amplifying the natural walking sounds led to a reduction in the asymmetry index of stance and stride times, whereas it inverted the asymmetry pattern in heel–ground exerted force. By contrast, augmenting high‐frequency bands led to opposite results. These gait changes might be related to updating of internal forward models, signaling the need for adjustment of the motor system to reduce the perceived discrepancies between predicted–actual sensory feedbacks. Our findings may have the potential to enhance gait awareness in stroke patients and other clinical conditions, supporting gait rehabilitation.

[ARTICLE] State-of-the-art research in robotic hip exoskeletons: A general review – Full Text

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Gait Rehabilitation - Foot Drop, Rehabilitation robotics on October 18, 2019

Abstract

Ageing population is now a global challenge, where physical deterioration is the common feature in elderly people. In addition, the diseases, such as spinal cord injury, stroke, and injury, could cause a partial or total loss of the ability of human locomotion. Thus, assistance is necessary for them to perform safe activities of daily living. Robotic hip exoskeletons are able to support ambulatory functions in elderly people and provide rehabilitation for the patients with gait impairments. They can also augment human performance during normal walking, loaded walking, and manual handling of heavy-duty tasks by providing assistive force/torque. In this article, a systematic review of robotic hip exoskeletons is presented, where biomechanics of the human hip joint, pathological gait pattern, and common approaches to the design of robotic hip exoskeletons are described. Finally, limitations of the available robotic hip exoskeletons and their possible future directions are discussed, which could serve a useful reference for the engineers and researchers to develop robotic hip exoskeletons with practical and plausible applications in geriatric orthopaedics.

Introduction

Most countries are reported with rising life expectancy and therefore a rapid increase in ageing population worldwide. Elderly people normally have physical deterioration and frailty, which imposes a heavy burden on the social health care system. The decreased physical capabilities owing to deterioration of neuromusculoskeletal system makes elderly people walking with a changed gait pattern and more cautious [1]. They generally have increased step variability and metabolic cost of walking, lower walking speed, shorter step-length, and reduced range of motion of the ankle, knee, and hip joints [2,3]. In addition, the elderly people have difficulties in maintaining trunk stability and have a risk of falls [4]. The lower limbs dysfunction and gait impairments are also common in elderly people, which could cause unnatural gait patterns [5,6]. Nearly three-quarters of all strokes occur in people over the age of 65 years. All those could reduce the mobility of elderly people and lead them to fewer independent lives and poor quality of life.

In addition, the patients with neurological disorders caused by diseases or injuries such as a stroke and spinal cord injury generally have muscle weakness, which could lead to insufficient force/torque at the hip joints during human locomotion [7]. These individuals often have decreased capacities of self-balancing and increased falling risk [8]. Therefore, approaches that can help elderly people and these patients to maintain a good walking pattern are desirable [9]. The past decade has witnessed a remarkable progress in research and development (R&D) of wearable medical devices for the patients with gait impairments [10]. The use of wearable medical devices such as robotic exoskeletons [11] and active orthoses [12] have become one of the most promising approaches to assist the individuals with gait disorders. It is predicted by a researcher that robotic exoskeletons would be commonly used in the community by 2024 [13].

Robotic hip exoskeletons integrate the robot power and human intelligence, and they can provide controllable assistive force/torque at the wearers’ hip joints with an anthropomorphic configuration. One application of robotic hip exoskeletons is on gait rehabilitation. They are able to train the wearers’ muscles and assist their movements for therapeutic exercise. The robot-assisted rehabilitation can release therapists from the heavy burden of rehabilitation training and provide long training sessions for the patients with good consistency. Human regular walking is able to reduce the risk of strokes and coronary heart disease, and hence to improve the physical and mental health [14]. Thus, it is promising to make human walking more efficient. Human effort is related to metabolic expenditure, and the other application of robotic hip exoskeletons is to augment human performance such as increasing the human strength and endurance.

By comparing with the human ankle joint, the hip joint needs higher metabolic cost for the generation of similar mechanical joint power owing to the differences in muscle characteristics [15]. Therefore, in addition to the robotic ankle exoskeletons developed for metabolic benefit [16], the hip joint actuating is also a promising strategy because large positive torque is provided by the human hip during the activities of daily living [17]. Robotic hip exoskeletons also have the potential to integrate into the factories. In warehouses and manufacturing environments, the workers often have to handle heavy goods, which could load their lumbar spine and increase the risk of physical injury such as low back pain and other work-related musculoskeletal disorders [18,19]. The work-related injuries could have a serious impact on the quality of life of these individuals. Robotic hip exoskeletons are able to assist these workers during manual handling of heavy-duty tasks.

The aim of this article is to review the aspects of engineering design and control strategies of robotic hip exoskeletons for the two applications, i.e., gait rehabilitation and human performance augmentation, and to discuss some possible future directions to improve the currently available robotic hip exoskeletons. We hope this review would provide useful information for the engineers and researchers to design desirable robotic hip exoskeletons, especially for those new to this field and would like to make contributions to this important multidisciplinary biomedical engineering and orthopaedic rehabilitation filed.

In this article, the biomechanics of the human hip joint and pathological gait of individuals with hip dysfunction are first presented before reviewing the mechanical structure, actuators, sensors, and control strategies of the existing robotic hip exoskeletons. Finally, this article discusses the limitations of the available robotic hip exoskeletons and their possible R&D directions with respect to clinical applications.

Biomechanics of human hip and pathological gait

To increase adaptability and achieve minimal interference, bioinspired design of robotic hip exoskeletons is required. This section presents a brief description of biomechanics of the human hip joint and the pathological gait pattern of individuals with hip dysfunction, which provides a basis for the design and control of robotic hip exoskeletons.

Biomechanics of normal human hip joint

The human hip joint is a ball-and-socket joint and joins the pelvis to the femur. It is composed of the cup-shaped acetabulum and femoral head, which are connected and supported by several tissues and muscles [20,21]. In human locomotion analysis, the human hip behaves as a spherical joint with three degrees of freedom (DOFs), i.e., flexion/extension, abduction/adduction, and internal/external rotation. A human gait cycle is defined as a sequence of movements during walking and is basically composed of the alternating stance phase and swing phase [22], as shown in Fig. 1. According to the gait analysis of people with a normal gait pattern [23], the human hip joint will generate positive work to bear the body weight, propel the body forward, and stabilize the trunk during the period of 0–35% of a gait cycle. After this phase, the hip joint angle will cross the zero degree and the leg will become vertical.

Download : Download high-res image (361KB)

Download : Download full-size image

Fig. 1. Normal gait cycle. The green lines represent the right leg, and the blue lines represent the left leg. The gait cycle is composed of the alternating stance phase and swing phase, and it starts when one foot contacts the ground and ends when the same foot contacts the ground again.

[…]

Continue —-> State-of-the-art research in robotic hip exoskeletons: A general review – ScienceDirect

[Abstract + References] A Wireless BCI-FES Based on Motor Intent for Lower Limb Rehabilitation

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Functional Electrical Stimulation (FES), Gait Rehabilitation - Foot Drop on October 7, 2019

Abstract

Recent investigations have proposed brain computer interfaces combined with functional electrical stimulation as a novel approach for upper limb motor recovery. These systems could detect motor intention movement as a power decrease of the sensorimotor rhythms in the electroencephalography signal, even in people with damaged brain cortex. However, these systems use a large number of electrodes and wired communication to be employed for gait rehabilitation. In this paper, the design and development of a wireless brain computer interface combined with functional electrical stimulation aimed at lower limb motor recovery is presented. The design requirements also account the dynamic of a rehabilitation therapy by allowing the therapist to adapt the system during the session. A preliminary evaluation of the system in a subject with right lower limb motor impairment due to multiple sclerosis was conducted and as a performance metric, the true positive rate was computed. The developed system evidenced a robust wireless communication and was able to detect lower limb motor intention. The mean of the performance metric was 75%. The results encouraged the possibility of testing the developed system in a gait rehabilitation clinical study.

References

via A Wireless BCI-FES Based on Motor Intent for Lower Limb Rehabilitation | SpringerLink