Archive for category Epilepsy

[WEB] How common is Epilepsy?

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Epilepsy on April 23, 2024

Epilepsy – An Overview

Epilepsy is not one single condition. Rather, it is defined as a spectrum of disorders that involve abnormal activity within the brain. “Epilepsy” means the same thing as the term “seizure disorders.” In epilepsy, abnormal brain waves disturb electrical activity, leading to seizures. Symptoms of epileptic seizures include having unusual sensations or emotions, behaving in unusual ways, or experiencing convulsions or loss of consciousness. Brain damage, illness, and irregular brain development can all cause abnormal brain waves that lead to seizures.

Approximately half of all people who have had one seizure will have more (typically within six months). However, in order to be diagnosed with epilepsy, a person must have had more than one seizure, and doctors must consider it likely that they will continue to have seizures. When a person has a seizure that lasts for more than 5 minutes, or a person has more than one seizure within a 5 minutes period (without returning to consciousness between the seizures), it is called status epilepticus.

Some forms of epilepsy last for a limited time, although the condition is often lifelong. Although there is no cure currently for epilepsy, there are many treatments available for the condition. About 70 percent of people with seizures can control them with proper diagnosis and use of medication.

There are many different types of seizures, and some people with epilepsy will experience more than one type. Some examples of seizure types include:

- Absence seizures

- Generalized tonic-clonic seizures

- Atonic (or akinetic) seizures

The History of Epilepsy

People have been aware of epilepsy and seizures for millennia. A Babylonian medical textbook made up of 40 tablets and dating to 2000 B.C. contains a chapter that accurately describes many of the different types of seizures known today. However, seizures were thought to be supernatural in cause — each seizure type was associated with a different evil spirit or angry god — so the treatments prescribed were spiritual.

Epilepsy in Ancient Greece

The word “epilepsy” comes from the Greek word “epilepsia,” meaning “to seize” or “to take hold of.” By the 5th century B.C., the Greeks still considered epilepsy a “sacred” disease. Yet the renowned ancient physician Hippocrates described epilepsy as a brain disorder. This was a radical idea for the time. He recommended physical treatments while also recognizing that if the seizures became chronic, the disorder was incurable.

Despite Hippocrates’ writings, epilepsy continued to be considered a supernatural condition for the next two millennia. People with epilepsy were subjects of immense social stigma, treated as outcasts, and even punished as witches. In many places, people who suffered seizures were prevented from going to school, working, marrying, and having children. There were a few people with prominent positions thought to have had epilepsy — including Julius Caesar, Tsar Peter the Great of Russia, Pope Pius IX, and Fyodor Dostoevsky — but most people with epilepsy were prevented from living as full members of society.

Epilepsy in the 14th Century and Beyond

During the Renaissance, some scientists tried to prove epilepsy was a physical, not spiritual, illness. Then, in the 19th century, neurology became a recognized medical discipline and the idea of epilepsy as a brain disorder became normal in North America and Europe. In 1857, Sir Charles Lacock introduced bromide of potassium as the first antiepileptic drug (AED).

In 1873, a British neurologist named John Hughlings Jackson first described epilepsy as we understand it today. Jackson showed that seizures are caused by sudden, brief electrochemical discharges of energy in the brain. In 1909, the International League Against Epilepsy was founded as a global professional organization of epileptologists.

By the 1920s, Hans Berger, a German psychiatrist, had developed the electroencephalogram (EEG) to measure brain waves. It showed that each type of seizure is associated with a different brain wave pattern. The EEG also aided in the discovery that specific sites in the brain were responsible for seizures and expanded the potential for surgical treatments. Surgery became a more widely available option by the 1950s.

The Development of Antiepileptic Drugs

The medication phenobarbital was identified as an AED in 1912, and phenytoin (sold under the brand names Dilantin and Phenytek) was developed in 1938. Carbamazepine (sold under the brand names Tegretol and Carbatrol) was identified in 1953. These drugs have since been approved by the U.S. Food and Administration (FDA) and continue to be used today.

An accelerated drug-discovery process began in the 1970s with the creation of the Anticonvulsant Screening Program, sponsored by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. The program helped scientists gain a better understanding of the brain and epilepsy. Scientists have strived to reduce serious side effects associated with the use of older AEDs through drug-development processes.

Keppra (levetiracetam) was approved by the FDA in 1999. Several newer drugs, including Vimpat (lacosamide), Briviact (brivaracetam), and Aptiom (eslicarbazepine acetate), have been introduced in the past 10 to 15 years. Other promising medications are also in the pipeline.

Social Stigma

The stigma around epilepsy has lessened as more people are able to effectively treat their seizures. However, epilepsy largely remains an “invisible” illness. Millions of people in developing countries do not have access to AEDs, and stigma and discrimination are still widespread, especially in places where people still believe that seizures have a supernatural cause.

How Common Is Epilepsy?

People of all backgrounds, races, ethnicities, and ages are equally affected by epilepsy. It is estimated that epilepsy affects 1.2 percent of the population of the United States and more than 50 million people worldwide, making it one of the most common neurological disorders. Approximately 45,000 children under the age of 18 are diagnosed with epilepsy every year in the U.S., and roughly 10.5 million children worldwide live with epilepsy.

Diagnosing Epilepsy

Neuroimaging capabilities have improved over the past few decades. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computerized tomography (CT) scans, and other techniques are able to detect more and more subtle brain lesions responsible for epilepsy.

Read more about diagnosing epilepsy.

Causes of Epilepsy

Causes of epilepsy include a wide variety of brain-related issues, such as structural damage, infectious diseases (like encephalitis), and genetic anomalies. Risk factors for epilepsy include:

- Age

- A family history of seizures

- Head injuries (such as traumatic brain injury or TBI)

- A history of seizures as a child

Read more about causes of seizures and epilepsy.

Types of Seizures

There are many types of epilepsy. Seizures are broken into two categories: focal seizures and generalized seizures. Focal seizures can be categorized by whether or not there is a loss of consciousness or awareness. Generalized seizures can be further broken down into absence, tonic, atonic, clonic, myoclonic, and tonic-clonic seizures.

Learn more about seizure types and symptoms of epilepsy.

Condition Guide

[Abstract] Neurostimulation for treatment of post-stroke impairments

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Epilepsy on April 8, 2024

Abstract

Neurostimulation, the use of electrical stimulation to modulate the activity of the nervous system, is now commonly used for the treatment of chronic pain, movement disorders and epilepsy. Many neurostimulation techniques have now shown promise for the treatment of physical impairments in people with stroke. In 2021, vagus nerve stimulation was approved by the FDA as an adjunct to intensive rehabilitation therapy for the treatment of chronic upper extremity deficits after ischaemic stroke. In 2024, pharyngeal electrical stimulation was conditionally approved by the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence for neurogenic dysphagia in people with stroke who have a tracheostomy. Many other approaches have also been tested in pivotal device trials and a number of approaches are in early-phase study. Typically, neurostimulation techniques aim to increase neuroplasticity in response to training and rehabilitation, although the putative mechanisms of action differ and are not fully understood. Neurostimulation techniques offer a number of practical advantages for use after stroke, such as precise dosing and timing, but can be invasive and costly to implement. This Review focuses on neurostimulation techniques that are now in clinical use or that have reached the stage of pivotal trials and show considerable promise for the treatment of post-stroke impairments.

Key points

- Neurostimulation techniques are ideally suited for use during stroke recovery owing to their ability to target anatomical structures or neuronal networks, alongside precise timing and dosing.

- Paired invasive vagus nerve stimulation has been shown to increase the number of people who achieve clinically important improvements in upper extremity impairment and performance of functional tasks following stroke. The treatment is now in clinical use in the USA.

- Several other neurostimulation techniques show promise for post-stroke impairments but definitive data from adequately powered trials are lacking.

- Pharyngeal electrical stimulation increases the odds of decannulation following tracheostomy and is under investigation as a treatment for post-stroke dysphagia.

[WEB] Tonic-Clonic Seizures Explained

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Epilepsy on November 7, 2023

Medically reviewed by Evelyn O. Berman, M.D. — Written by Brooke Dulka, Ph.D.

When people think of epilepsy, they often envision jerking limbs and a loss of consciousness. These symptoms describe a type of seizure called tonic-clonic seizures. Generalized tonic-clonic seizures were previously called grand mal seizures.

Here’s what to know about these seizures, including symptoms, causes, diagnosis, and treatment options, as well as what you can do if you witness someone having a tonic-clonic seizure.

Symptoms of Tonic-Clonic Seizures

The term “tonic-clonic” describes what happens during the two phases of these seizures.

“Tonic” refers to the stiffening, or sustained contraction, of muscles. During the tonic phase, which generally lasts less than 30 seconds, a person experiencing typical symptoms of epilepsy may also:

- Let out a cry or groan as air pushes past the vocal cords

- Lose consciousness

- Fall down

- Bite their tongue

- Foam at the mouth

“Clonic” refers to rhythmic jerking, usually of the face, arms, and legs. This phase can be brief or last a few minutes. If the jerky movements continue for more than 5 minutes, the seizure becomes a neurological emergency called status epilepticus.

After the clonic phase ends, the person’s body will begin to relax. This relaxation sometimes includes the muscles of the bladder or bowels, causing accidental urination or a bowel movement. As the person then slowly regains consciousness, they may be confused, irritated, tired, or depressed. These symptoms are all normal for a person coming out of a tonic-clonic seizure.

What Causes Tonic-Clonic Seizures?

Tonic-clonic seizures are caused by abnormal electrical activity in the brain. When this electrical activity occurs on both sides of the brain at once, the seizures are called generalized tonic-clonic seizures. If the activity starts on one side and progresses to both sides, the seizures are called focal to bilateral tonic-clonic seizures (formerly called secondarily generalized seizures).

Abnormal electrical activity in the brain has been associated with several risk factors. Some of these risk factors are genetic, as tonic-clonic seizures tend to run in families. Tonic-clonic seizures also can be related to:

- Brain injury or structural damage

- Infection

- Substance misuse, including alcohol misuse

Diagnosing Tonic-Clonic Seizures

Some people have one tonic-clonic seizure and never have another. Other people have many tonic-clonic seizures, which may help doctors make an epilepsy diagnosis. Reaching a diagnosis of an epileptic disorder can be time-consuming and frustrating. You may need to go to several doctors and neurology specialists before your health care team can make a conclusion.

The most important diagnostic tool a neurologist might use to diagnose epilepsy is an electroencephalogram (EEG), which measures brain waves. EEG testing may reveal abnormal brain activity in between seizures to help establish a diagnosis. MRI scans, which visualize the brain, may also help your doctor determine if there is a structural cause of seizure activity.

How Are Tonic-Clonic Seizures Treated?

Tonic-clonic seizures are typically treated with antiepileptic or anti-seizure medications. One study found that three drugs, (Tegretol), phenytoin (Phenytek), and valproate (Depakote), completely stopped seizures in roughly 50 percent of participants.

Lamotrigine (Lamictal) has also proved to be a successful treatment option for tonic-clonic epilepsy.

In other cases, such as for status epilepticus, a class of antianxiety medications called benzodiazepines is recommended to end the seizure.

Not all medications work for everyone, and your doctor may prescribe several different drugs before finding the one that works best for you.

Staying Safe During a Seizure

Watching someone have a seizure can be scary. By understanding what to do and what not to do, you will be better prepared to deal with the situation. If someone is having a tonic-clonic seizure, here are some safety tips to keep in mind:

- Stay calm.

- Remain with the person.

- Roll the person onto their side immediately if they have food or water in their mouth.

- Place something soft under their head.

- Try to protect the person from injury.

- Time the seizure.

It’s also important to know these tips on what not to do:

- Don’t try to put something in the person’s mouth. It is not true that someone having a seizure can swallow their tongue.

- Don’t restrain the person.

- Don’t offer food or drink, which could cause choking.

Talk With Others Who Understand

MyEpilepsyTeam is the social network for people with epilepsy and their loved ones. On MyEpilepsyTeam, members come together to ask questions, give advice, and share their stories with others who understand life with epilepsy.

Do you or a loved one have tonic-clonic seizures? Do you have any tips for being prepared to deal with these situations? Share your experience in the comments below, or start a conversation by posting on your Activities page.

[Quiz] Can Alcohol Trigger Seizures?

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Epilepsy on September 22, 2023

An epileptic trigger describes anything that can prompt a seizure. A few common epileptic triggers include physical or emotional stress, flashing lights, eating certain foods, and even lack of sleep. But one potential trigger that is confusing for many people with epilepsy involves alcohol.

If you’re living with epilepsy, you might be curious about the relationship between alcohol and seizures. Take this five-question quiz to better understand how alcohol and seizures may be connected.

[WEB] What To Avoid When Taking Keppra: Energy Drinks, Other Drugs, and More

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Epilepsy on September 14, 2023

If you take levetiracetam — sold as Keppra, Elepsia, and Spritam — to help manage your epilepsy, you may want to pass on that second Red Bull or frappuccino. Though levetiracetam can effectively treat certain types of seizures, taking it along with large quantities of caffeine — as well as with alcohol and other medications — can make it less effective or even cause harmful side effects.

Levetiracetam is an anti-seizure medication that comes in a few different forms: tablet, oral solution, or intravenous (IV) solution. Most people who take levetiracetam are prescribed the oral tablet form and they take it on a schedule every day at home. The IV form is given only in the hospital.

Members of MyEpilepsyTeam who take levetiracetam sometimes ask about how their epilepsy medication might interact with their favorite beverages. “I know alcohol messes with medications, but since when do people say Red Bull or any energy drink has an effect on seizure medication?” a member asked.

Another member described a seizure and hospitalization after consuming an energy drink. “I’ve noticed since I’ve been drinking these energy drinks, preferably Red Bull, Amp, Rockstar, or Monster … that it’s made me very dehydrated and I’ve had an increase of seizure activity … which ended up putting me into the hospital.”

Read on to learn about drinks that can interact with formulations of levetiracetam, what drink alternatives are available, and when to talk to your doctor about your anti-seizure medication.

Drinks To Avoid While Taking Levetiracetam

Certain drinks can increase your risk of having a seizure. These include beverages containing caffeine, sugar, and alcohol.

Energy Drinks

The makers of energy drinks such as Red Bull, Monster, 5-Hour Energy, and Rockstar market these beverages as an effective way to boost your physical and mental performance. However, these drinks aren’t regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and they can be harmful if you’re not careful about how much you consume.

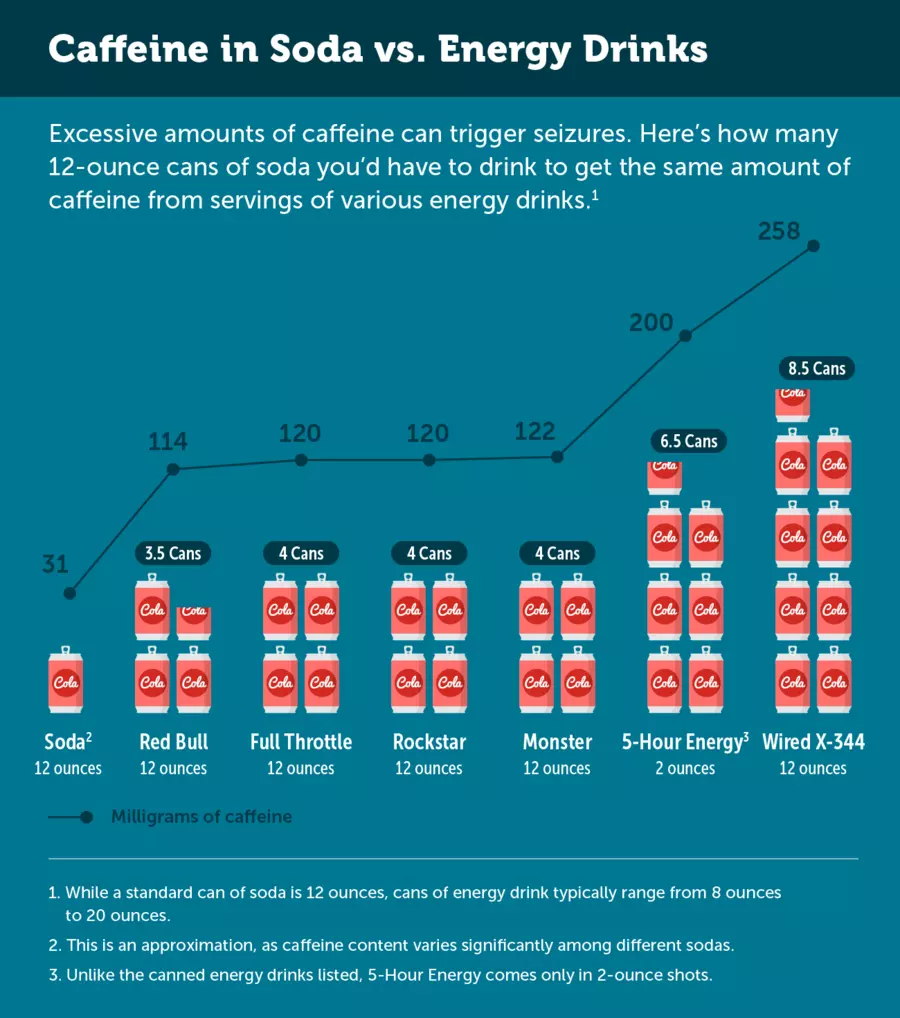

Energy drinks can be dangerous for anyone because they contain high amounts of caffeine, which is a stimulant. The amount of caffeine within an energy drink is usually substantially higher than what’s in a regular cup of coffee or can of soda.

Research has found that energy drinks can trigger seizures, even in people with no history of seizures. A 2014 study showed that children and adolescents are at particular risk for seizures from consuming energy drinks. Dehydration –– a known side effect of energy drinks –– can also lead to seizure.

Notably, some researchers believe that it’s not the stimulant itself that increases a perons’ risk of seizure. Rather, it’s the energy “crash” that happens after it wears off.

Additionally, research involving rats has found that high doses of caffeine may interfere with levetiracetam’s anticonvulsant action — that is, its ability to control seizures. More research is needed, though, to see whether the same holds true for humans.

High doses of caffeine can also cause:

- Tremor

- Agitation

- Heart rhythm abnormalities

- Heart palpitations (e.g., rapid fluttering heartbeat)

- High blood pressure

- Breathing difficulties

- Lightheadedness

Additionally, insomnia (an inability to sleep) can be a side effect of energy drinks. Tiredness or drowsiness is strongly linked with triggering a seizure.

Side effects of overdosing on caffeine can be severe enough to sometimes require a trip to the hospital.

Energy drinks often contain other ingredients that can affect your brain when consumed in high quantities, such as sweeteners, amino acids, guarana, and taurine.

Other Caffeinated Beverages

Caffeine from other sources, including caffeine shots and pills, coffee, soda, and tea, can also impact your seizure risk — especially if you have a low seizure threshold.

One member of MyEpilepsyTeam said “No. I don’t touch energy drinks or anything with caffeine because they will create triggers which lead to seizures. Especially with Keppra. Energy drinks will do twice the damage that coffee will do because of two to three times the caffeine.”

Alternatives to Caffeinated Drinks

In general, it’s safest for people who experience seizures to stay away from energy drinks and other beverages that contain high amounts of caffeine. Staying away from beverages with high amounts of sugar is also a good idea to prevent energy crashes. Be sure to drink plenty of water, given that caffeine and sugar can be dehydrating.

Tea, especially green tea, is a good alternative to highly caffeinated energy drinks when consumed in moderation. Decaffeinated coffee, teas, and sodas can also work well.

Instead of relying on caffeine and other stimulants for energy boosts, consider making some dietary changes. Eating a balanced diet high in protein is important for maintaining good energy levels, whether you’re living with epilepsy or not.

Alcohol

Moderate to large amounts of alcohol can also adversely interact with anti-seizure medication, making you feel intoxicated more quickly and lowering your seizure threshold. Alcohol withdrawal can also cause seizures and be life-threatening.

Mixing energy drinks and alcohol — which is a popular trend — can be even riskier than drinking alcohol by itself. One study used a medication to induce seizures in animals and compared the seizure onset time for those given an energy and alcohol to those who weren’t. The seizure onset time was significantly shorter in the energy drink and alcohol group.

Health experts advise that people who are taking anti-seizure medication avoid consuming alcohol. Like caffeine, drinking excessive amounts of alcohol can trigger seizures in people who’ve never had one before.

Medications To Avoid While Taking Levetiracetam

Several medications can interact with levetiracetam and cause serious health problems. In some cases, two medications should never be used together. In other cases, they can be as long as the doses are adjusted or other appropriate precautions are taken.

Medications and supplements that may have undesirable interactions with levetiracetam include:

- Methotrexate

- Orlistat

- Calcifediol

- Gingko

- Other anti-seizure medications, including carbamazepine and benzodiazepines

- Antihistamines (i.e, allergy medications)

- Antidepressants

- Antipsychotics

- Cannabis

- Clonidine

- General anesthesia medications

- Anticoagulants

- Opioids

This list does not include every medication that interacts with levetiracetam. If you are unsure about a medication, a new beverage, or a new food, it is always advised to seek professional medical advice. Note, too, that some drugs and medications can increase your risk of seizures.

Talk to Your Doctor

When taking any medication –– but especially an anti-seizure medication –– it’s important to follow the directions, dosing, and schedule directly as prescribed by your neurologist. A lot of different substances can have drug interactions, and it’s important to make sure you’re not accidentally increasing your risk for a seizure while taking Keppra.

Sometimes, even things we don’t think of can interact with medications. Herbs, supplements, and natural remedies can sometimes seriously affect the medications you’re taking or your risk of having a seizure. Be sure to talk with your doctor before adding anything new to your diet — including energy drinks.

Talk With Others Who Understand

MyEpilepsyTeam is the social network for people living with epilepsy and their loved ones. On MyEpilepsyTeam, more than 114,000 members come together to ask questions, give advice, and share their stories with others who understand life with epilepsy.

Are you taking levetiracetam for epilepsy and wondering about the risks of energy drinks? Share your experience in the comments below, or start a conversation by posting on your Activities page.

[Infographic] Epilepsy: What People Don’t See

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Epilepsy on September 12, 2023

[WEB] Fatigue and Epilepsy

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Epilepsy, Fatigue on August 7, 2023

Medically reviewed by Amit M. Shelat, D.O. — Written by BJ Mac

What It Feels Like | Causes | Management | Get Support

Epilepsy refers to a spectrum of disorders that alter normal brain activity, causing seizures. Because epilepsy can affect many processes coordinated by the brain, people living with this condition can experience many different symptoms. One of the most common symptoms of epilepsy is fatigue — chronic and overwhelming feelings of exhaustion, tiredness, or weakness. Fatigue is a much more common symptom in people living with epilepsy than in the general population.

Feelings of exhaustion and weakness can affect daily quality of life. Luckily, there are some ways to help manage epilepsy-related fatigue.

What Does Fatigue With Epilepsy Feel Like?

The fatigue felt by people living with epilepsy is characterized by mental and physical experiences of persistent and extreme weakness, tiredness, and exhaustion.

One MyEpilepsyTeam member described being more emotional as a result of fatigue: “Does anyone feel so tired that they feel sad? This often happens to me. I am on a lot of medication, and my seizures are not under control, so I guess I have many reasons to be tired.”

Another member reported that fatigue causes them daytime sleepiness: “Does anyone experience sleepiness during the day? I just noticed it today, and a friend said I was snoring.” One member described the impact of seizure-related fatigue on her quality of life, writing, “For several years, I wake up after a seizure, and I am tired for up to seven days and in bed pretty much all day every day. That is the primary reason I lost my job.”

What Causes Fatigue in Epilepsy?

Several factors can cause a person with epilepsy to experience fatigue.

Depression

Depression is a known comorbidity (co-occurring condition) of epilepsy, with symptoms that vary from person to person. A study using measures called the Fatigue Severity Scale and Fatigue Impact Scale revealed a high prevalence of depression-related fatigue among people living with epilepsy.

This fatigue may sometimes trigger epileptic seizures. A cycle can start to develop: Depression causes fatigue, which contributes to seizures. These seizures then cause more fatigue, which contributes to depression, and so on. Talk to your doctor about how to treat depression in order to break this cycle.

Many MyEpilepsyTeam members agree that dealing with depression is a common aspect of living with epilepsy: “I never thought I would ever have to deal with depression. With epilepsy, depression is a daily battle.”

Nocturnal Seizures

Another important risk factor of developing fatigue when living with epilepsy is poor sleep or sleep impairment. In particular, nocturnal seizures (seizures that occur while a person is sleeping) can affect a person’s sleep quality.

A person is considered to have nocturnal seizures if more than 90 percent of their seizures occur when sleeping, which is the case in up to 45 percent of people living with epilepsy.

Both generalized and focal seizure types can occur as nocturnal seizures. Nocturnal seizures tend to occur during the first, lighter stages of sleep or upon waking.

One MyEpilepsyTeam member described nighttime seizures as a source of fatigue: “I recently had several nocturnal seizures, and I am now very exhausted. It will take three days for my body to get back to normal. It takes so much out of you.”

Another member described how nocturnal seizures interrupt her sleep rhythm and cause fatigue the next day: “Does anyone else ever have a seizure in their sleep and find it hard to fall back asleep? Then during the day, it can completely take your energy away.”

Postictal Fatigue

There are several stages to a seizure:

- Prodromal phase — When symptoms begin

- Aural phase — When altered perception or sensations occur

- Ictal phase — The actual seizure

- Postictal phase — Recovery time after a seizure

- Interictal phase — The time in between seizures

Postictal phases have been found to have higher chronic fatigue scores and fatigue impact scores than ictal phases, with people reporting more fatigue and lower energy during the postictal phase. In other words, the recovery period after a seizure is a time of intense fatigue.

Many members reported needing to sleep due to intense fatigue during this phase. “I always go to sleep after a seizure,” wrote one member. “It’s often compared to running a marathon. Your muscles are weak, everything hurts, and you are plain tired.”

Antiseizure Medications

Some antiepileptic drugs are known to cause fatigue. A change of medication or time to adjust to your treatment plan may be needed to reduce this fatigue.

One member responded to another’s query about medication-related fatigue: “When I took that medication, I experienced fatigue, anxiety, fear, anger, and mood swings.” They offered some great advice: “When side effects become unmanageable, it’s time to talk to your neurologist and ask for a drug that has fewer side effects.”

Read more about epilepsy treatment options.

Managing Epilepsy-Related Fatigue

Managing fatigue with epilepsy can be challenging because its different causes can be interrelated. Tracking symptoms of fatigue and discussing causes and treatments with your health care team is the best place to start.

Treat Depression

The British Epilepsy Association published a study that measured fatigue and depression using the Epworth Sleepiness Scale and the Beck Depression Inventory. The results highlighted the importance of managing depression in order to better manage fatigue with epilepsy.

Medical interventions such as antidepressant medications may help to curb depression. Psychotherapy (talk therapy) and other forms of counseling may also be beneficial. Healthy lifestyle habits can complement efforts to curb depression.

One member swore by exercise to help depression: “I took a six-mile run this afternoon to help with my depression.” Another said they rely on a support animal: “Our therapy cat is super sweet and loves to cuddle with me and my wife. She helps alleviate my stress, anxiety, and depression.”

Manage Postictal Symptoms

Working with your doctor to determine what your usual postictal symptoms are may help you better manage those symptoms.

Your doctor may order an electroencephalogram during the postictal phase to analyze brain changes and better treat or manage future episodes.

Being prepared for the post-seizure phase with a routine incorporating help from people you trust can lessen the impact of postictal symptoms like fatigue. Emotional support and validation from people you trust can have a positive impact on the heavy emotions that can accompany this seizure phase. Taking care of your immediate physical needs after a seizure may also help.

Maintain Healthy Habits

Eating a regular, healthy diet and snacks can help to keep up energy levels and fight off excessive daytime sleepiness. Maintaining a healthy weight, hydrating, and getting regular physical activity may also help boost energy levels.

One member found that following a routine and avoiding triggers had the biggest impact on managing fatigue: “Eat healthily, get eight to ten hours of sleep a night, no alcohol, take medication daily and at the same time every day, and take care of your mental health (reduce stress, learn coping skills, and enjoy what you have). In general, avoid the typical triggers.”

Improve Sleep

One member lamented the cycle of fatigue, poor sleep, and seizures: “My husband has a very hard time getting to sleep and staying asleep. When he has a bad night of sleep, he usually has a seizure. Then, he is so exhausted he sleeps almost all day and can’t get to sleep at night, and such is this vicious cycle.”

Another MyEpilepsyTeam member suggested they try yoga for better rest: “Yoga helps you notice what’s happening in your body and helps you gently let go of stress. It helps you learn how to breathe deeply and evenly and what positions are best to help your body rest. Yoga teaches how to empty your mind of intrusive thoughts and sounds.”

Practicing sleep hygiene protocols can also help you get more high-quality sleep. Some tips for better sleep with epilepsy include:

- Keep a dark bedroom at night and let sunlight in upon waking.

- Practice and maintain a bedtime routine with consistent sleep and wake times when you can.

- Limit screen use, especially an hour before bed.

- Avoid consuming too much caffeine during the day.

- Get regular physical activity that is enjoyable to you.

- Try some breathing exercises and meditation, especially at bedtime.

According to one MyEpilepsyTeam member, a referral to a sleep clinic might help: “I had a good visit with the sleep clinic on Zoom. If you guys are having trouble sleeping, you should ask for a referral to a sleep clinic. He really took the time to give me tips to improve my sleep without medication.”

Talk To Your Doctor

Psychotherapy is a tried-and-true way of minimizing fatigue in people living with epilepsy. Talk to your doctor about this option and other approaches that may help you manage your fatigue.

Find Support

Learning how to cope with fatigue is often best done alongside others who understand what you are going through. On MyEpilepsyTeam, more than 100,000 members form a social network and online support group to talk about a range of personal experiences, struggles, and successes.

Do you experience fatigue with epilepsy? How do you manage it? Share your experience and tips in the comments below, or by posting on MyEpilepsyTeam.

[WEB] Which Types of Epilepsy Can Be Treated With CBD?

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Epilepsy on August 3, 2023

- Cannabidiol (CBD) is a derivative of hemp that can be used to treat severe forms of epilepsy in children and adults, including Dravet syndrome and Lennox-Gastaut syndrome.

- Although CBD products are available over the counter, only prescription CBD medications are approved and regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

- CBD does not cause intoxication and is generally safe to use, but it can interfere with other medications.

Finding an effective treatment for epilepsy is extremely important but not necessarily easy. This is particularly true for people with treatment-resistant epilepsy, also known as refractory epilepsy. Cannabidiol is one possible treatment option that has gained attention recently.

CBD and tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) are both derivatives of the Cannabis sativa plant, commonly referred to as marijuana. THC is the chemical that is responsible for the “high” associated with smoking marijuana. CBD has grown in popularity ever since the passage of the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 in the U.S., which made it legal to sell hemp and hemp products.

Although marijuana and hemp are technically the same plant, they differ in THC content. Hemp contains incredibly small amounts of THC (less than 0.3 percent by dry weight). Because there is such a small amount of THC found in the hemp plant, you don’t have to worry about getting intoxicated from CBD products, such as CBD oil. CBD has been studied for potential medical use, including treating several neurological and psychiatric conditions such as epilepsy.

Which Types of Epilepsy Can Be Treated With CBD?

There are many forms of epilepsy that occur in people of all ages. Clinical studies have shown that CBD is most useful for severe or treatment-resistant epilepsy. In some studies, CBD has also proved particularly effective and therapeutic for children with severe epilepsy.

Two types of epilepsy are particularly hard to treat and can be quite dangerous:

- Dravet syndrome, also known as severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy

- Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, a combination of several types of seizures

CBD has been shown in clinical trials to help reduce seizure frequency in individuals living with Dravet syndrome or Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. These same studies have shown that CBD is safe to use long term in both children and adults, with one clinical trial treating individuals for 96 weeks.

CBD has also shown promising results in treating tuberous sclerosis complex and febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES), two other severe conditions associated with seizures.

How Does CBD Work To Control Epilepsy?

The exact process by which CBD helps control seizures related to epilepsy remains unknown. However, scientists have theories. Some researchers theorize that CBD affects seizures through its interaction with a receptor on neurons (nerve cells) within the brain. A receptor is like a lock on a neuron that can only be activated with a specific key, such as a neurochemical. In this case, a G protein-coupled receptor acts as a gate for releasing calcium, and calcium is critical for brain cell activity and communication.

Scientists also think a neurochemical called adenosine may interact with CBD. Adenosine is the brain’s natural anticonvulsant (or anti-seizure medication). Research in rats supports the idea that CBD increases how much adenosine is available in the brain.

Another brain cell receptor that may be affected by CBD is TRPV1 — also known as the capsaicin receptor and the vanilloid receptor 1. This receptor is more prevalent in people with epilepsy, and CBD is known to make these receptors less sensitive.

Altogether, the complex interactions between CBD and several different brain receptors and adenosine are believed to work with each other to decrease seizure activity.

Over-the-Counter and Prescription CBD Products

CBD products, including tinctures, concentrates, and capsules, are readily available over the counter at a wide variety of stores, from gas stations to specialty CBD boutiques. However, over-the-counter medical cannabis products are not approved by the FDA or regulated in the same way as prescription CBD products. This means these products carry no real guarantee of safety or efficacy. Further, they may not contain the dose of CBD claimed on the label.

Prescription CBD products, on the other hand, are regulated by the FDA. These products must meet certain quality and purity standards. Therefore, you are more certain to acquire safe and effective CBD through a prescription from a doctor. Currently, one formulation of CBD has secured FDA approval for the treatment of epilepsy: Epidiolex. The drug secured approval in 2018 and is indicated for Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and Dravet syndrome in people ages 1 and up.

Understanding Possible Risks and Side Effects of CBD

If you or a loved one is living with a treatment-resistant form of epilepsy, CBD may help. You should also understand the possible risks and side effects of CBD in order to protect yourself.

So far, scientific research and clinical trials (studies that determine a drug’s safety and effectiveness in people) show that CBD is generally safe and has few to no negative side effects. Studies show that CBD alone does not negatively affect blood pressure, heart rate, or breathing functions. Further, there are no apparent changes in psychological function when CBD is taken by itself, without THC.

There is one big caveat in using CBD: It can cause interactions with other drugs or medications, including antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). Specifically, CBD interacts with other substances that are metabolized by a group of enzymes known as cytochromes P450, which are responsible for breaking down CBD. This means that if you take CBD and another drug that is broken down by these enzymes, CBD may interfere with the level of the other medication in your body.

CBD has been shown to interact with drugs including:

- Antiepileptic drugs

- Steroid medications

- Antidepressants

- Anxiety medications

- Calcium channel blockers

- Antipsychotics

- Antibiotics

- Antihistamines

- Anesthetics

- Beta-blockers

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

Drug interactions can be dangerous and carry serious risks. Because CBD has the potential to interact with other drugs, seek medical advice from your doctor before beginning to take over-the-counter CBD products.

Finding Support as You Treat Epilepsy

Are you having trouble finding an effective way to manage your seizures? Members of MyEpilepsyTeam, the social support network for people with epilepsy and their loved ones, can relate. When you join MyEpilepsyTeam, you gain a community of more than 112,000 people who are living with epilepsy and thousands more who care for a loved one with the condition.

Have you tried CBD to manage your seizures? Did you use a prescription or over-the-counter CBD product? Share your experiences or questions in a comment below, or start a conversation on your Activities page today.

[WEB] Epilepsy vs. Seizures: Understanding the Terminology

Posted by Kostas Pantremenos in Epilepsy on April 29, 2023

Medically reviewed by Evelyn O. Berman, M.D.

Article written by Barbara Boughton

Although any seizure may be frightening and cause for concern, experiencing one doesn’t mean you have epilepsy.

A person experiences a seizure when there is a sudden surge of abnormal electrical activity in their brain, caused by complex chemical changes in neurons or nerve cells. Seizures are not a disease — they are symptoms of many types of conditions that affect parts of the brain. In a seizure, you may experience symptoms of a temporary loss of consciousness or loss of awareness.

A seizure may also cause:

- Involuntary movements

- Disturbances in taste, vision, and hearing

- Changes in mood and cognitive function

Epilepsy is a disorder characterized by recurrent unpredictable (or unprovoked) seizures. For epilepsy to be considered as a diagnosis, a person must have had two or more unprovoked seizures more than 24 hours apart.

Triggers that may provoke seizures differ from person to person but can include:

- High fever

- Low blood sugar

- Alcohol withdrawal

- Brain injury

- Dehydration

- Missed meals

- Stress

- Sleep deprivation

These triggers may provoke a first seizure in people who are susceptible, but they may not have epilepsy. At the same time, such triggers can help bring on seizures in people with epilepsy.

Sixty-five million people have epilepsy worldwide, and more than 3 million have epilepsy in the United States, according to the Epilepsy Foundation.

The cause of epilepsy varies by age. In some people, epilepsy is a result of genetics or a change in the structure of the brain that brings on seizures. Three out of 10 children with autism spectrum disorder may have seizures. In young adults, seizures are also frequently seen in those with head injuries or tumors. In people over age 65, the most common cause of new-onset seizures is stroke. Six out of 10 seizures are idiopathic (without a known cause).

The International League Against Epilepsy has developed new terms to define seizure types in epilepsy:

- Generalized seizures affect groups of cells on both sides of the brain at the same time.

- Focal seizures affect a group of cells in one part of the brain.

- When the onset of a seizure is unknown, it’s called an unknown-onset seizure. A seizure may also be referred to as having an unknown onset if it is not witnessed by anyone, such as when someone living alone has a seizure at night.

The Difference Between Having Epilepsy and Having a Seizure

Several medical events or conditions are not epilepsy and may cause seizures.

Many people have a single or first seizure sometime in their life. They can be provoked or unprovoked. In most cases, single seizures do not recur and are not a sign of epilepsy unless the person has brain damage, a family history of epilepsy, or neurological abnormalities that cause seizures.

It’s not uncommon for children to have seizures during a high fever. These children are not usually treated with any kind of antiseizure medicine unless there are indications that the seizure may recur. These signs could include nervous system damage or a seizure that is especially prolonged or complicated.

Seizure Types Not Caused by Epilepsy

According to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, an estimated 5 percent to 20 percent of people diagnosed with epilepsy are believed to be misdiagnosed — they have actually experienced a nonepileptic seizure. Physically, these seizures look the same as those caused by epilepsy, but they are not linked with an excessive and abnormal electrical discharge in the brain.

Nonepileptic seizures can have a psychological cause. In clinical practice, they are referred to as psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES). A history of trauma is one risk factor for PNES, and these seizures can be treated with cognitive behavioral therapy and other psychological treatments. A sign of PNES includes a lack of response to antiseizure drugs.

Medical conditions that cause nonepileptic seizures include:

- Narcolepsy — Sudden unreliable bouts of sleep

- Tourette syndrome — Repetitive involuntary tics

- Cardiac arrhythmia — Irregular heartbeats

- Eclampsia — Seizures that happen during pregnancy or shortly after giving birth

- Impaired liver or kidney function

- Abnormalities in the blood’s salt levels

If you experience a seizure, it is important to be evaluated by clinicians and a specialist in neurology. An electroencephalogram (EEG) can help detect if there are any abnormalities in brain waves, ideally 24 hours after a first seizure. The test may be useful in diagnosing epilepsy and in determining whether antiepileptic drugs will be beneficial.

Epilepsy and Recurrent Seizures

Epilepsy is a spectrum disorder, meaning that it has different causes, is marked by different seizure types, and its severity varies from person to person. There are many different types of epilepsy. Some people with epilepsy have very infrequent seizures. Others may experience seizures many times a day.

Most people diagnosed with epileptic seizures can control their symptoms with antiepileptic drugs, surgery, or lifestyle changes. However, as many as 30 percent to 49 percent of those with epilepsy continue to have recurrent seizures. Treatments and health care now available do not completely control epileptic seizures.

Most forms of epilepsy require lifelong treatment, but in some people, the seizures eventually go away. The chances of becoming seizure-free are better in those whose seizures start in childhood or have been effectively controlled by medication.

Some people who have epilepsy that can’t be controlled by drugs may undergo surgery to remove a small defined part of the brain or lesion where the seizures originate, and some may become seizure-free after surgery. Yet, such surgery is usually a last resort and is only tried in certain types of treatment-resistant epilepsy. The good news is that many people with epilepsy lead productive lives, and our understanding of seizures and their treatment is advancing rapidly.

Talk With Others Who Understand

MyEpilepsyTeam is the social network for people with epilepsy and their loved ones. On MyEpilepsyTeam, more than 108,000 members come together to ask questions, give advice, and share their stories with others who understand life with epilepsy.

Are you living with epilepsy? Share your experience in the comments below, or start a conversation by posting on your Activities page.